The veiled oyster mushroom (Pleurotus dryinus & Pleurotus levis) is one of the more obscure varieties of edible oyster mushroom I know. While they're not quite as good as some of their cousins, they're a very safe beginner mushroom with distinct characteristics that are great for practicing your identification skills.

Background

Veiled oysters are in the Pleurotus genus making them a true oyster mushroom, and probably the most distinct I know of. Originally placed in the genus Agaricus like button mushrooms, they've have had their classification rearranged a lot over since the early 1900's.

To date they've been placed in 4 different genuses and have many synonyms including Agaricus and Pleurotus corticatus, Panellus dryinus, Armillaria dryina, and others.

Found across North American, these are a common wood decomposer like other pleurotoid fungi, typically found growing on living or dead hardwood trees and fallen logs. They appear sporadically throughout the year through spring, summer and fall.

Most oyster mushrooms have a few varieties of trees they seem to favor, but Veiled oysters, at least from my experience seem to have a slightly wider range. Oak and beech trees are some of the most common they can be found on, but I've also picked them on hawthorn and horse chestnut trees.

Veiled Oyster Mushroom Identification

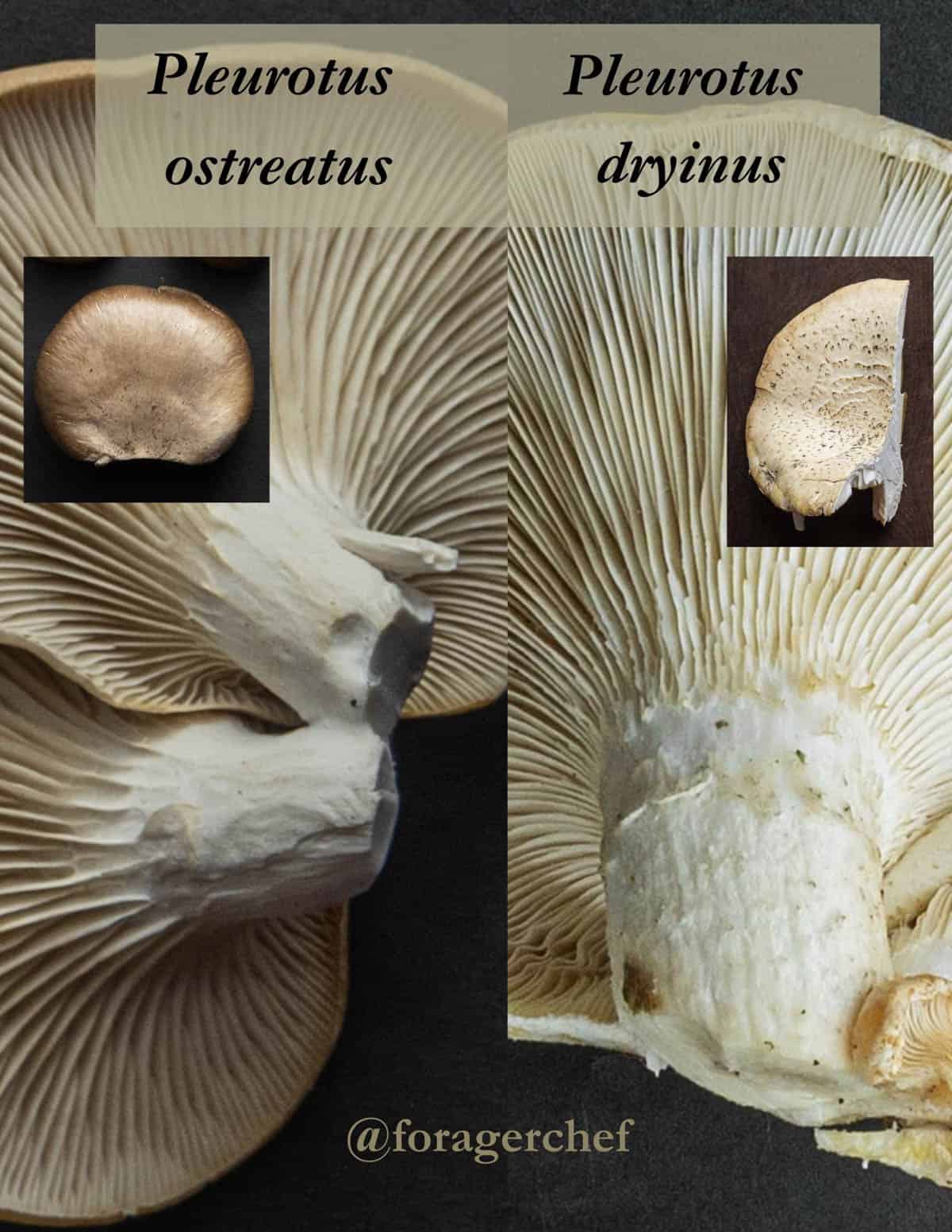

Unlike most oyster mushrooms, the veiled oyster has a distinct cap and stem. The stem is very tough and connected to the cap at a more or less central point.

Other oyster mushrooms like Pleurotus ostreatus usually have a stem that's slightly off-center, if they have one at all.

The white or cream colored cap is covered in tiny hairs that has much rougher texture than any other species of oyster I've picked, especially when mature.

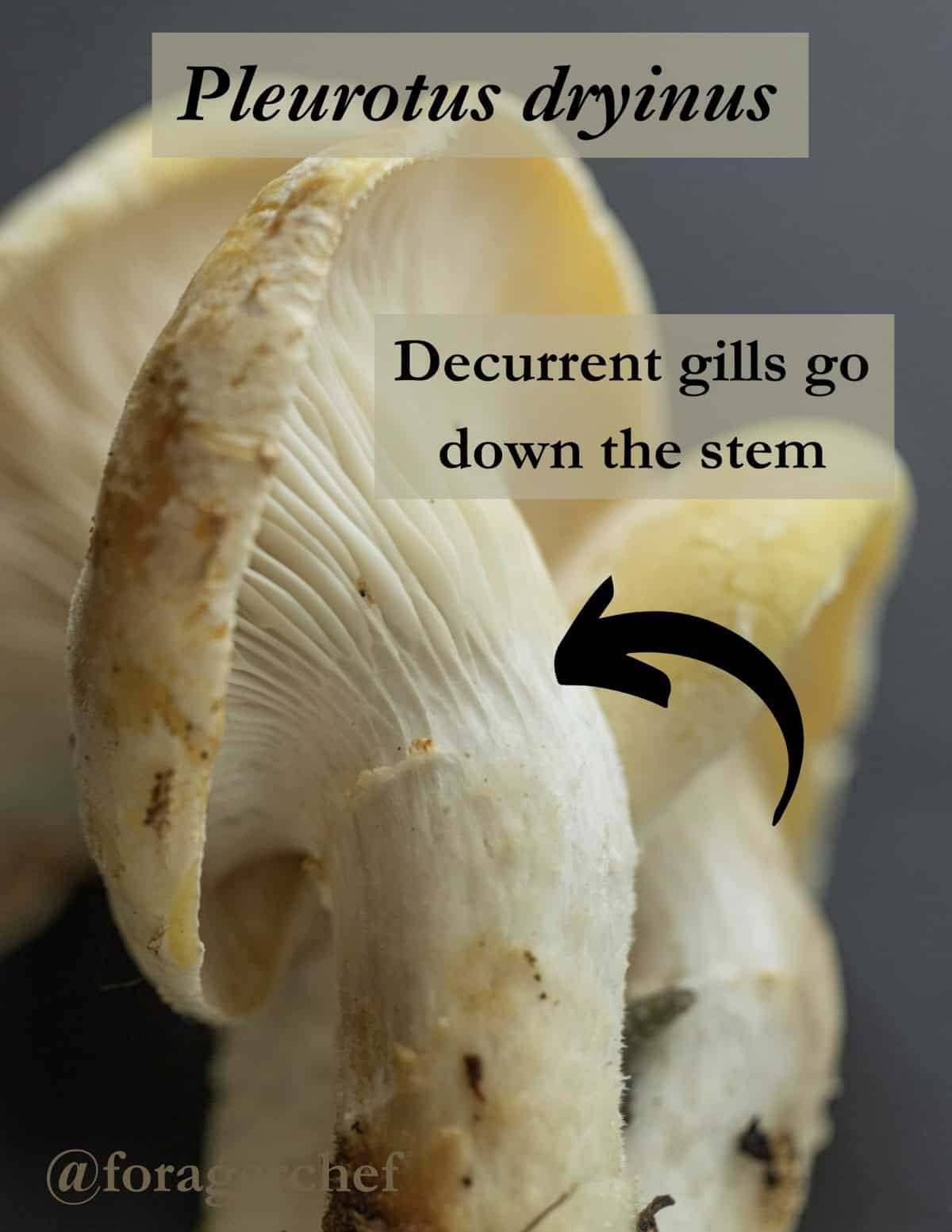

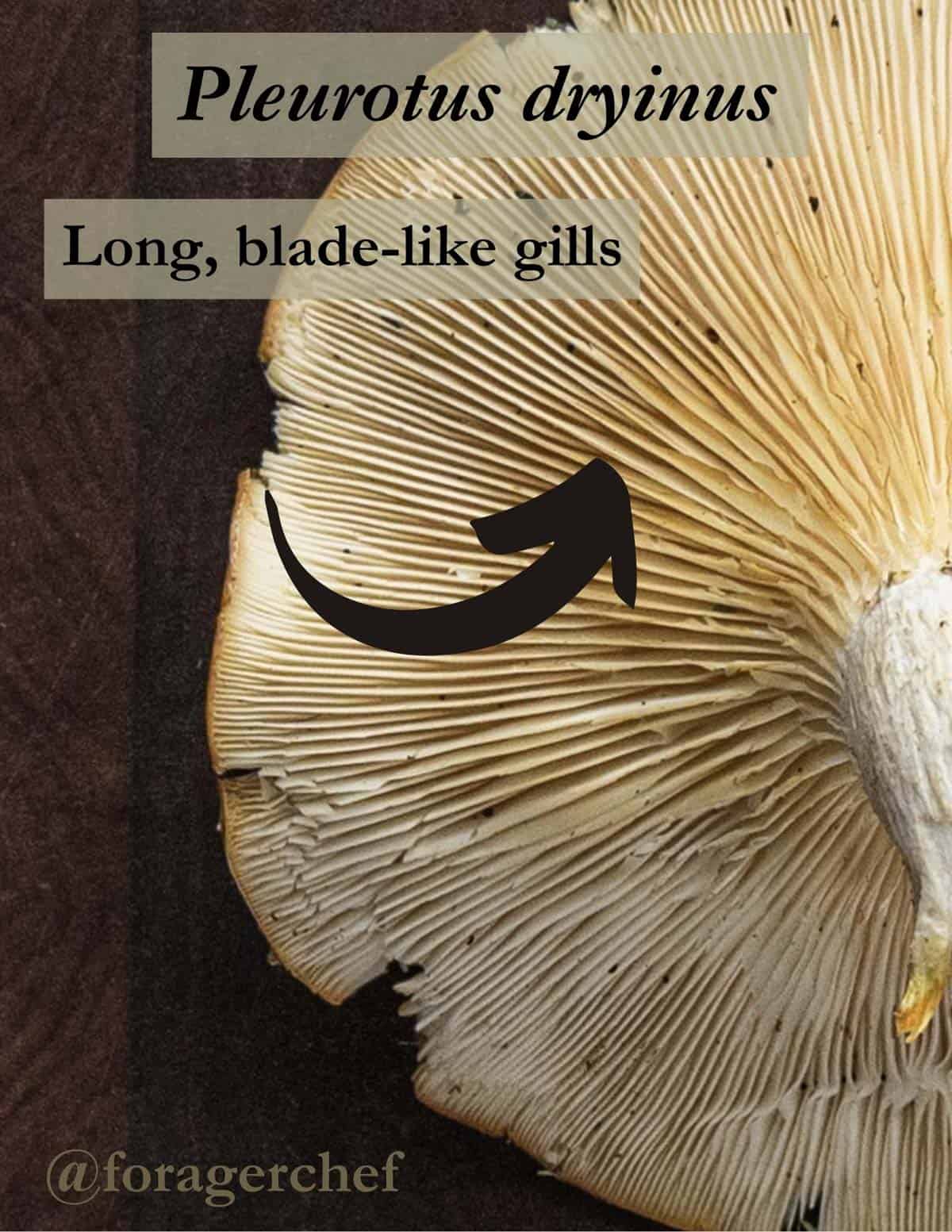

Like all mushrooms in the genus, they have decurrent gills that run partially down the stem. Run your hands underneath the cap and you'll also notice long, blade-like gills that flap under your fingers.

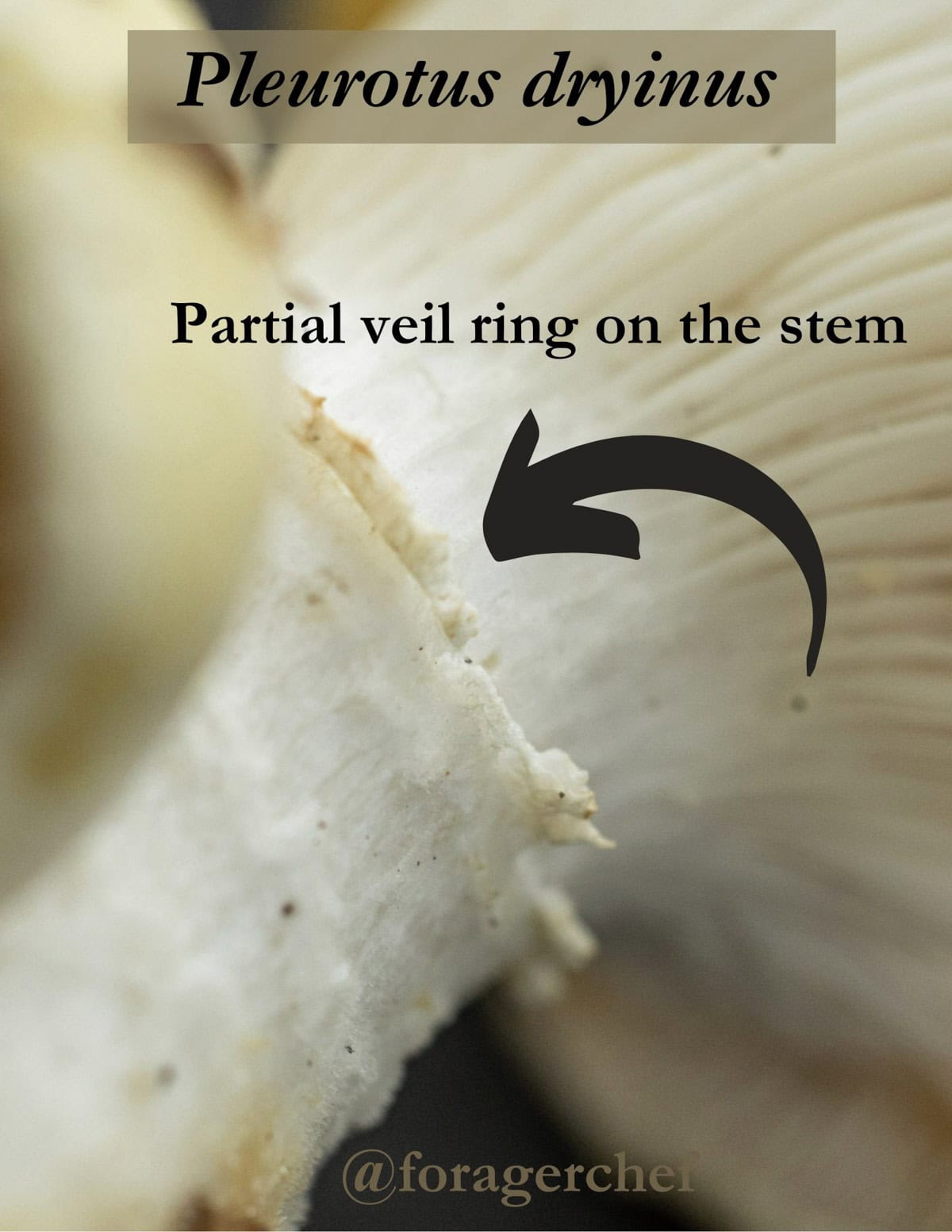

It's namesake comes from the partial veil on the stem, another distinct characteristic that makes them different from their cousins.

Pleurotus Dryinus vs Pleurotus Levis

One of the more confusing aspects of veiled oysters is that there's currently two accepted species. They're extremely difficult to separate but there are a few characteristics that could be taken into account. Either way separating the two is a bit of a moot point as both are edible.

Mycologist Michael Kuo says P. levis is typically associated with warmer weather and P. dryinus is a cold weather mushroom. Here's his post on them.

Anna McHugh says P. levis has a softer cap she compares to the texture of a moleskin journal, while P. dryinus has a more rough, fuzzy cap. She has a nice video describing some of the differences.

Veiled Oyster Mushroom Look Alikes

These are a very safe mushroom to get to know and all the mushrooms that resemble them I know of are edible. Here's the two most common I see confused with them.

Hypsizygus ulmarius

The elm oyster (Hypsizygus ulmarius) is probably the easiest mushroom to confuse with veiled oysters. Both of these edible mushrooms can be found in cold weather and like to grow from knots and wounds in trees.

Even so, the mushrooms are relatively easy to separate visually and from their growing characteristics. Elm oysters prefer elm trees and boxelders, where veiled oysters prefers oaks where I live. Elm oysters also have a very smooth, velvety cap, and always lack a ring on their stem.

Neolentinus lepidius

Another edible look alike I've only seen mentioned in David Arora is the train wrecker (Neolentinus lepidius).

The train wrecker also has a slightly rough cap and a stem that's tough as nails, but it's serrated gills and shaggy, coarse stem that lacks a partial veil ring set it apart. They also seem to prefer different trees, and I usually see them on downed conifer logs instead of hardwoods.

Cooking

I'll be upfront and say these are my least favorite of all the wild oyster mushrooms I've eaten. They're quite chewy unless very young with a mild flavor about as interesting as a boiled potato, which doesn't have to be a bad thing.

Sliced thin and harvested when young they can make a pleasantly chewy addition to stir fries and sautes. As they're mostly texture, ginger, garlic soy and stir-fry sauces can help add some interest to them.

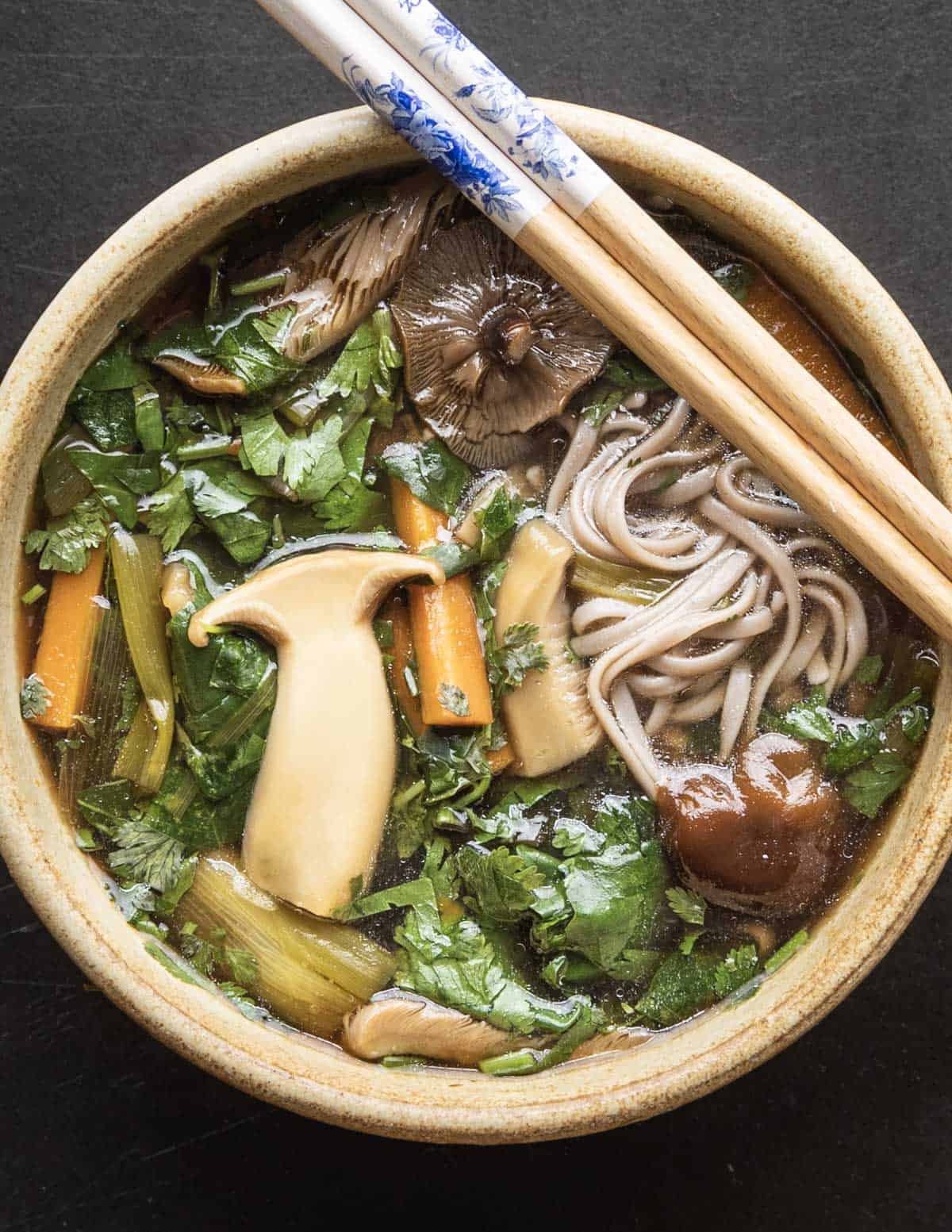

If you find them small and young, they can be fun in a mix of fall mushrooms where they can blend into the background. My oyster mushroom soup with soba noodles is a good place to start.

The most important thing to know here besides trying to get the mushrooms young is that, besides being chewy and very mild tasting, they bugs love them more that any oyster mushroom I harvest.

The silver lining is that these are common mushrooms to find in the fall, and fungal gnat larvae are usually absent when it's cold out where I live. If it's warm outside I rarely check to see if they're edible.

Just like other mushrooms that can be tough with age like the pheasant back, slicing them paper thin or mincing to make duxelles can get around the texture. Thinly sliced they can be dried to make something like my Italian mushroom soup. Their chewy texture also makes them a great candidate for mushroom jerky.

Bethany

I just found these in my woods this week and learned how to identify them!! I’ve just found your blog recently and started watching your show and am just enjoying your content so much. The mushrooms went straight in my dehydrators as we had just also harvested a basket of black trumpets. What a great feast we’ve been eating from our woods!! Thank you for your inspiration and fantastic recipes. I’m excited to make your Runza recipe soon. Thank you. Keep it up.

I love to joke that we’re eating like paupers when we are eating our chanterelles and oyster mushrooms. What a gift nature gives us.

Alan Bergo

Hey thanks Bethany. I'm so glad the site's been helpful for you.