Borcht didn't start out as a soup made with beets. Originally it was made with wild cow parsnip. Don't believe me? Read on.

Ukraine has been on everyone's mind lately, so I thought it would be appropriate to dive into their national dish: Borscht (or maybe it's Borshch?).

As random as it might sound, borscht is something I've read about a fair amount about, as the famous tart stew of beets (and all its variations) are inextricably connected to wild food.

I never knew anyone that ate borscht growing up--I hated beets. It took me until my late twenties to have my first taste during a stage (working for free for a day with the potential for employment) at St. Paul's Moscow on the Hill with Chef Gary Krasner. I thought the soup was ok, but just ok.

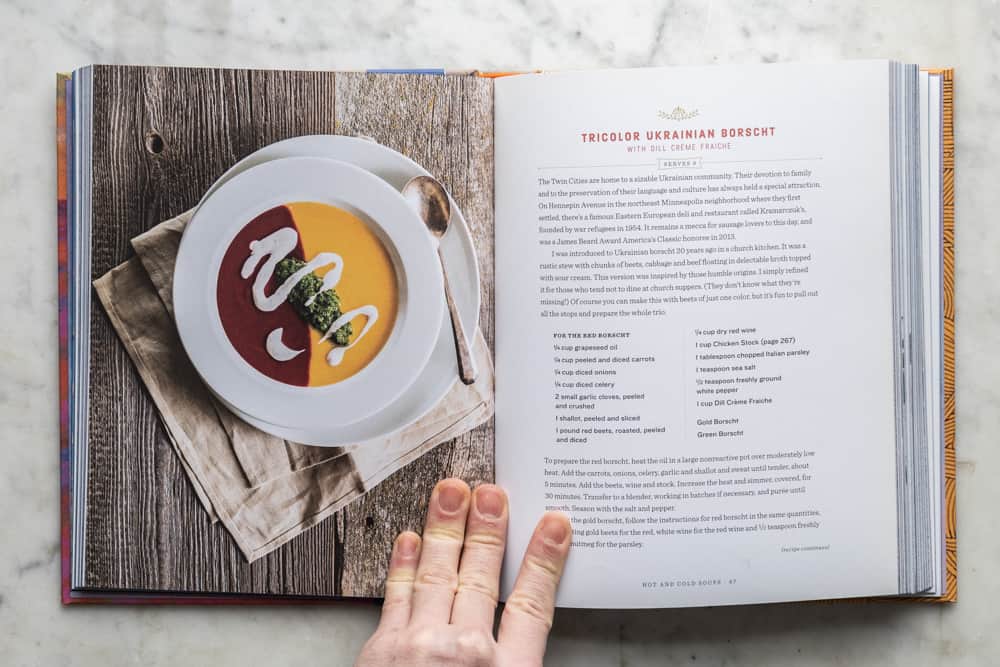

A few years later, I tasted another borscht recipe while I was cooking and styling Chef Lenny Russo's cookbook. At one of our quick office debriefs for the shooting schedule, Chef printed me off a food styling feat: a tri-color borscht, with all the soups ladled into a bowl at the same time so the individual colors stay intact.

The tri-color borscht remains one of the most tedious things I've ever had to cook for a camera. More so, making three different soups all called "borscht" left me confused. If each of the three soups I made for the soup were all borscht, what the heck was borscht anyway?

"There is even "green" borshch made with lemony-tasting sorrel leaves or nettles that grow wild in the countryside and are enjoyed by all." Annette Ogrodnik Corona, The New Ukranian Cookbook.

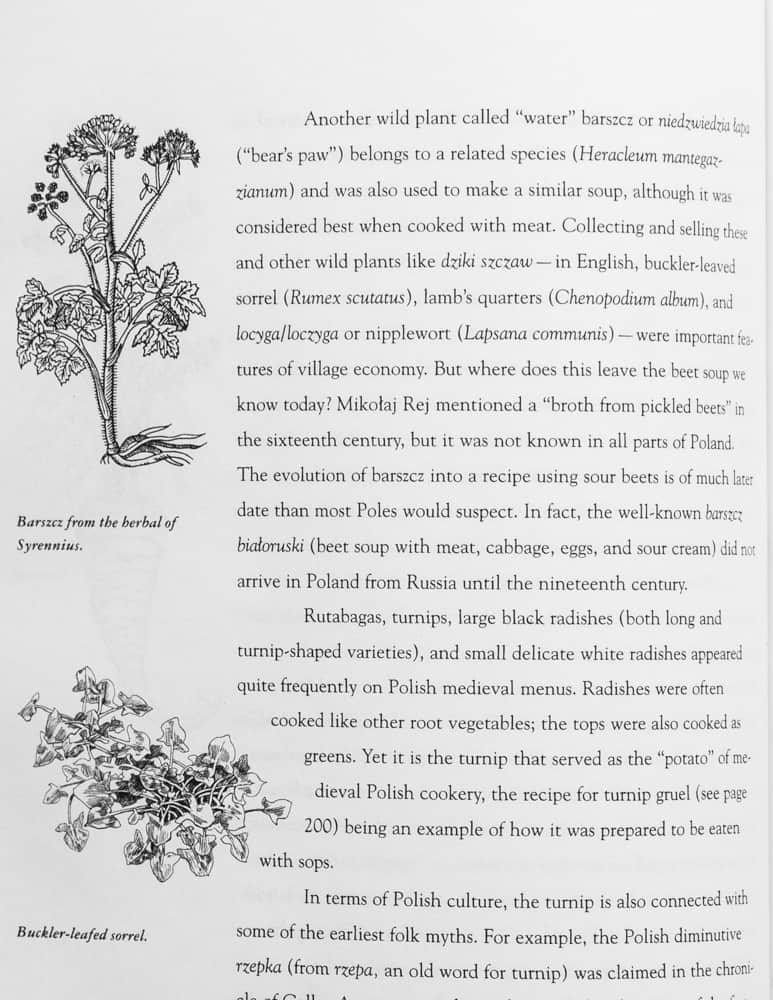

Later I learned from talking to a mushroom seller from Russia that there were many variations of borscht, with the classic red version being only one, although most I've seen do contain beets. Green borscht, a sour soup mostly made with sorrel or even nettles, is undoubtedly the closest modern equivalent to the ancestral version, but I'll get to that in a second.

Borscht: a plant and a soup

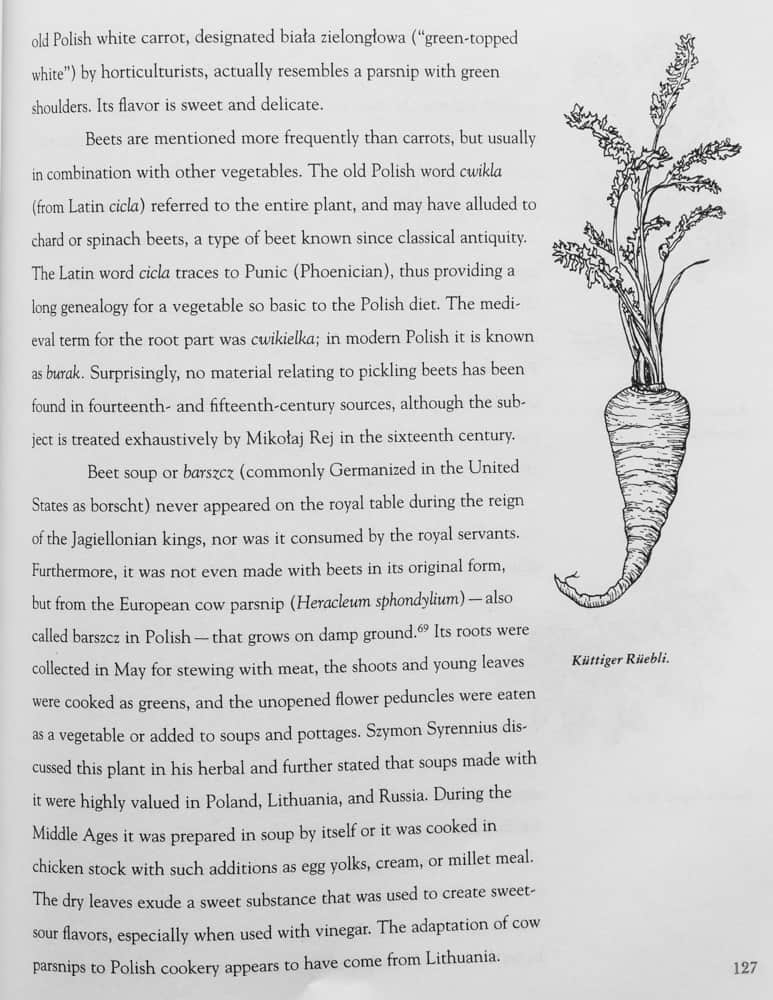

To foragers in my circles obsessed with plants, the etymology of borscht seems pretty well known, and, unlike a lot of things in the same vein, surprisingly well documented. Google "where does the word borscht come from" and you'll see right away that the name comes from, and describes both a soup, and the plant cow parsnip (in Eastern Europe it will be Heracleum spondyllium, which you may remember from my post on Golpar).

Long story short, borscht is a soup, but also refers to the plant used to make it, or at least it used to. As happens with language, words and their meanings change, ebbing and flowing slowly over time due to how they're being currently used.

Linguistic quirks aside, the ancestral borscht is fascinating. Not only was the original version made from cow parsnip (and probably other Apiaceae as I infer from the excerpt/picture below) but it's also well documented that the plant was fermented before it was made into soup, or possibly a sour drink like kvass made from the plant was used to season it (beet kvass is used to season borscht to this day), as the soup should be slightly tart.

Fermented Cow Parsnip

While I wrote my book, I was determined to make a historically accurate borscht to understand what the original version tasted like using lacto-fermented cow parsnip leaves and stems.

I have fermented many, many things, and, I have to say that the aroma of fermented cow parsnip is one of the most foul things I've put in my mouth, and it's not just me--at least two other foragers I know, both experts who know much more than me, have tried the exact same thing and found it completely inedible. I suspect there's something lost in translation somewhere.

Undoubtedly the plant was fermented and used to make soup, but the method of how to have it not be skunky and nauseating is beyond me. If you have some info on the process, or other insight, please leave a comment. Regardless, sauerkraut juice is also added to sour soups, and I think it's the perfect substitute.

The following is one of two cow parsnip-based borscht I've made that tasted good enough to serve to other people. It's a variation on the modern green borscht from The New Ukrainian Cookbook.

Instead of cow parsnip, you could also use nettles, or even better (and more sour) a combination of nettles and sorrel. It's a good soup, thickened with a sour cream liaison and flavored with plenty of dill. Sauerkraut juice provides the tang, and is traditional, but you can add lemon juice to taste in a pinch.

Related Posts

Pheasant Back Spring Vegetable Soup

The Original Borscht, with Cow Parsnip

Ingredients

Green Borscht

- 4 oz ¾ cup diced carrot

- 8 oz 1.5 cups diced potato

- 5 oz 1 cup diced celery

- 5 oz 1 cup diced onion

- 4 oz ¾ cup diced celery root (optional)

- 2 large cloves garlic finely chopped or grated on a microplane

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 6-8 oz or Roughly 3-4 cups chopped cow parsnip leaves and stems, preferably more stems than leaves or a combination of wild leafy greens like nettles and sorrel.

- 5 cups meat or vegetable stock such as chicken

- ½ cup sour cream

- ¼ cup heavy cream

- 4 tablespoons all purpose flour

- 1 tablespoon chopped fresh dill

- 2 tablespoons chopped Italian parsley

- ¼ cup sauerkraut juice or to taste, or lemon juice to taste in a pinch

- Kosher salt to taste

Serving

- Fresh chopped dill

- Chopped hard-boiled egg

- Extra sour cream optional

Instructions

- Sweat the carrot, onion, celery, potato, garlic and celery root if using in a 3 quart or similar-sized pot for 5-10 minutes or until softened. Add the meat or vegetable stock, bring the mixture to a simmer and cook until the vegetables are tender.

- Add the greens and cook until soft, about 5 minutes.

- Meanwhile, in a separate bowl, mix the cream, sour cream and flour until homogenous and smooth. Spoon in a couple tablespoons of warm broth from the pot, stir to combine and loosen the cream mixture, then pour it into the pot and stir.

- Add the dill and parsley. Bring the pot back to a simmer and cook until slightly thickened, double check the seasoning for salt and adjust until it tastes good to you. Serve each bowl garnished with chopped fresh dill and sliced or chopped hard-boiled egg. I usually add extra sour cream at the table too.

Jacqui

I took me a very long time to realise that the Polish, Ukrainian and French words for this plant seem to be cognate.

In French, Heracleum spondyllium is called "Berce'" which looks to me as though it shares a root with "Borscht" or "Barszcz". Or maybe the French adopted the Slavic name for the plant.

Emily Nebergall

I harvested cow parsnip for the first time near my home in western Washington this last weekend. It was at a perfect stage and I got some young shoots as well as slightly more developed young leaves. I blanched these and nibbled various bits and subjected a few of my common victims for new experiments to the taste test as well and all of us agreed that the cow parsnip tasted very strong and more like a cleaning product than food, although my boyfriend was less averse to it than others (he might have just been trying to be nice). Is this normal? I might experiment again with different preparations, this is an abundant plant where I live and id like to take advantage of it. Perhaps it is more enjoyable toned down in combination with other foods as a component of a dish and not on its own?

Alan Bergo

Yes, you're not going to be cooking and eating bowls of cow parsnip like you would nettles. If I use it in a dish it's typically with other greens, and in small amounts. Slow-cooking will help soften the flavor too, as in soups. If you don't like it, don't give up-you have to try the unopened flowers. The flavor of those is mild and delicious and they don't have the same strong aroma you're describing.

Emily Nebergall

Thank you!!! I will persevere in my quest to enjoy these. The flowers will be coming among soon, and I’ll experiment with smaller quantities and slower/longer cooking in the meantime

Jacqui

I just composted my lactofermented hogweed (=cow parsnip) leaves. I didn't believe you and figured something had gone wrong in your fermentation, expert though you be, but "foul" is a kind description of the smell and taste. Did not, yet, try Tom's or Leva's suggestions about temperature or sourdough. Might ... not bother. I'm sure fresh hogweed and sauerkraut or kimchi would do the job.

Alan Bergo

If I close my eyes I can still smell it. Once other people started telling me they’d tried it and it smelled awful I got more at peace letting that culinary mystery stay unexplored 🙂

Chef Biraj

Honestly, as a chef, I never cook or make Cow Parsnip Borscht. Basically, I prefer the Indian recipe. But I am sure I will try this recipe. Thanks for the nice posting.

Alan Bergo

I don't think anyone really makes it, but the history is valuable.

Alex

Bullshit! Where is the red beets!

No red beets- fake borsch!!!

Alan Bergo

I literally just showed you that the ancestral borscht was made from plants with documentation from a book whose references are over 500 years old. The idiotic comments I deal with sometimes really surprise me.

Corinne

I knew someone was going to say that. I've gotten the same reactions when I tell people I'm making this recipe. I love this soup. I included it in a 5-course meal that we are planning to serve tonite at our Foraged Fest in Troy, New York. I'll let you know how it goes over, but we LOVED it when we tried it out a few weeks ago. SO GOOD. And with bunches of foraged greens (sochan, nettles, dandelion greens, and goutweed + cow parsnip!) the soup was SOOO GREEEN, yay!

Alan Bergo

Hey thanks Corinne, glad you liked it. Such an interesting soup.

Ieva

Hi, Alan,

I'm from Lithuania, so I grew up eating various borsch :). I'm also historian interested in food history and edible wild plants history. If you don't like plain fermented heracleum (I know this smell...), try to ferment it with rye sourdough starter. Just mix chopped leaves with active whole meal rye sourdough starter and some salt and leave it overnight. It's old traditional recipe to ferment wild greens for soups like borsch.

Alan Bergo

Leva, this is great! Thanks for sharing. I'll give it a shot this year.

Daniel

Why don't you ferment the root instead of the aerial parts?

Alan Bergo

Hey Daniel, a couple reasons. First, the roots of cow parsnip can be a real pain to dig, and, as it's a lethal harvest, it would deplete my wild gardens in some places where they're easily accessible, but not in large colonies. Also, the roots aren't pleasant to eat, and, they would have a different flavor from the green parts. You could sure chop them up, ferment them in brine, and use the brine in cooking, discarding the roots after.

Tom

I'm not from Eastern Europe, but i've fermented european cow parsnip (H. sphondylium) many times using lacto-fermentation. The right method to avoid the foul-tasting result you described is to keep temperature quite low. Low temperatures won't stop lacto-fermentation, just slow it down. Then check regularly until you achieve the desired acidity.

If you have access to giant hogweed (H. mantegazzianum), this is something i discovered recently ; if you let the

young stems dry at low temerature in the oven they gonna smell and taste strongly like coconut due to coumarins. When preserved in sugar they make wonderful coconut-tasting candied "fruits".

Jacqui

Hi Tom,

Was delighted to read your comment because I have been flirting with the idea of eating H. mantegazzianum for ages but had not dared.

So when you say "stems" do you mean the leaf petioles or do you mean the flowering stalks, or both? And do you do anything to tame the hairs (blanching and then rubbing with rubber gloves on (the way I remove the prickly parts of the H. sphondylium to make it more appealing to picky eater) or does the drying do the trick and you don't notice the hairs when they are covered with sugar? Can you safely touch the stems after drying? No worries about this?

I am being careful because I can't even touch H. sphondylium without gloves on anymore.

Thanks for any advice!!

Mg

So warming to read about the history of borscht on your website. The older or more original form, of the green soup, remind me of something that is common in Bulgaria, particularly in the countryside, in springtime. It’s called spring soup.

Usually consist of whatever green herby plants or fresh leaves are growing, added to sautéed grated carrots. Water-based broth. Green plants usually include, because of availability, fresh-picked nettles, green garlic sprouts (they look like green onions) and green onions, chopped to whatever size one likes (I’ve never seen a recipe, not like it matters), while green plums, usually roughly chopped, are thrown and cooked with everything for a sour taste.

Maybe seasoned with chubritsa, which in English is summer savoury. It’s lovely all together.

Alan Bergo

That Spring soup sounds great.

Brent Stuart Ferguson

Consider mixing east Asia with Eastern Europe. Look at kimchee recipes and substitute parsnip for cabbage to make your sour borsch stock. You will love a little added heat in your soup this way.. Instead of tricolor, i go for tri flavor. Sour, sweet. And spicy. Each bite is a pleasant surprise.

Alan Bergo

Sour sweet spicy is a great combo. First thing I think of with that profile is Georgian Kharcho.

Linda Reinhart

I must try borscht with pushki (cow parsnip). I have make borscht ever since we moved to the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska over half a century ago. Its ingredients are perfect for here (much climate similarity). I always used meats - moose, caribou, reindeer (domestic caribou) Polish sausage and wild duck. It was always a favorite of our 6 children. I must try it with pushki. Since finding your blog I have been fascinated with using that plant - probably the worst thug in our gardens! We have been using nettles as our first spring greens for many years, but I never put them in borscht.

Bette

Thank you, Alan,

I just made borscht a few weeks ago, and this article expands my horizons. My ancestry is Eastern European and my heart is aching. Thanks for being a ray of light.

Bette

Gina

Is it possible that a bread sour was used as the souring agent in the past, rather than fermented cow parsnip? Bialy barszcz uses a smoked meat stock with bread sour added to taste. Robert & Maria Strybel's Polish Heritage Cookery have a simple recipe for bread sour: place 8-10 slices of stale Polish rye or black bread in a sterilized crock or jar. Cover with 6 cups lukewarm pre-boiled water. Cover the jar mouth with cheesecloth and let stand at room temperature 3-4 days until sour. Strain through cheesecloth into bottles and refrigerate.

Kelly Holman

I wonder how you fermented the cow parsnip. Using a traditional crock or a modern anaerobic set up might make a difference. It definitely makes a difference in the levels of bacteria.

https://www.onevibrantmama.com/fermentation-friday-why-i-wont-ferment-without-a-separate-airlock-part-i/

Tammy Hartmann

Thank you for the fascinating history lesson on Borscht! As a Ukrainian, having grown up on the Canadian prairies, I have eaten Borscht my whole life. This is the first time I’ve seen a ‘green’ variety and since I have Sorrel growing in my garden, I will most definitely have to give this recipe a try. I will have to gather some nettle as well. As you indicated at the outset, our hearts and minds are definitely preoccupied with the horrors of what is currently happening in the Ukraine. It seems unimaginable. I am praying there is somehow a conclusion to the Russian invasion, sooner than later.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Tammy. Yeah, it's just awful. I hope it ends soon.