Sweet galium is a wild herb you can use as a substitute for vanilla. It's widespread across North America and easily identified.

For most of my career working with wild food I've ignored cleavers (Galiums) with one or two exceptions. Galium triflorum or sweet-scented bed straw is the exception, and I now harvest the plant each year for commercial projects and personal use.

I struggle to think of a wild herb with as much potential as both a cash crop and a seasoning as G. triflorum. If you know sweet woodruff, everything I mention in this post applies to that plant as well-they're closely related.

To really understand why I like this plant so much, I think it's helpful to consider a few different cleavers to get a sense of how they're used. Typically, when you say cleaver, or bedstraw, the plant that will probably come to mind for most people is Galium aparine, and mostly people will have memories of pulling it off of their pants after a hike.

Some people eat Galium aparine and probably others I haven't heard of. Grass clippings are also "edible". Sure, Galium aparine is edible, but it's also stringy, tough, and generally unpleasant to eat.

To me, it's one of the poster children of wild plants (along with plantain) that, while technically edible, tend to give wild food a bad name because they're just not great to eat. Eating it raw also gives me "scratchy plant throat" as do the stems of violets and a few other plant parts.

Of all the galiums I've tried, Galium mollugo is the one I eat as a vegetable occasionally, and even then, it is only the very young tender growing tips or meristems. Harvesting enough for a salad would be a lot of work, and to be honest, I wouldn't eat a whole salad of them either, although they make a nice addition to a blend of greens.

Galium triflorum though, is a completely different creature. If you were to eat the plant like a vegetable, it would be tough too, even tougher than Galium aparine. The secret of Galium triflorum is its smell: a sort of cross between fresh cut grass, hay and vanilla-scent compounds related to the coumarin contained in the plant.

If you're ever heard of sweet woodruff, (a close relative used in Europe as a flavoring for German Maiboyle/May wine) the smell is identical. For the sake of ease in explaining to people how I use the plant, I call it a couple names: wild vanilla and sweet galium are two I like.

Is it safe?

But, isn't coumarin a drug you ask? And, isn't it dangerous to take with blood thinners? Mention the word coumarin and some people might think the plant isn't safe, citing examples of it being dangerous when combined with blood thinning drugs, derivatives being used as poison, as well as farm animal deaths occurring from a mold on clover. Monica Wilde, a forager I know in passing on social media, breaks it down much more succinctly than I can. See her excellent post on safety and sweet woodruff for more.

Unmodified (natural) coumarins do not affect the action of warfarin or similar anticoagulant, blood thinning drugs. This is because coumarins do not deplete vitamin K which affects the blood coagulation system. Modified coumarin – such as dicoumarol or coumadin – is different. Dicoumarol is synthesised and known as warfarin (Coumadin) and is used as a. rat poison. In nature coumarin can be modified by certain fungal infections which occur if the plants are are harvested while wet or damp. Sweet woodruff picked on a dry day and properly dried without any mould developing will not contain modified coumarins.

I think this is a good example of a good distinction to make between the differences of natural and synthetic derivatives. Sure, Galium triflorum contains coumarin, but so does cinnamon, which is also toxic in large doses. Another thing I like to say is, if you don't want a medicinal effect, don't consume a medicinal dose.

With Galium triflorum and sweet woodruff, a medicinal dose is far beyond what any human would possibly consume using the plants in normal use. There's a big difference in someone drinking a glass of May Wine, and a cow that gets sick from eating five pounds of moldy clover.

Identifying

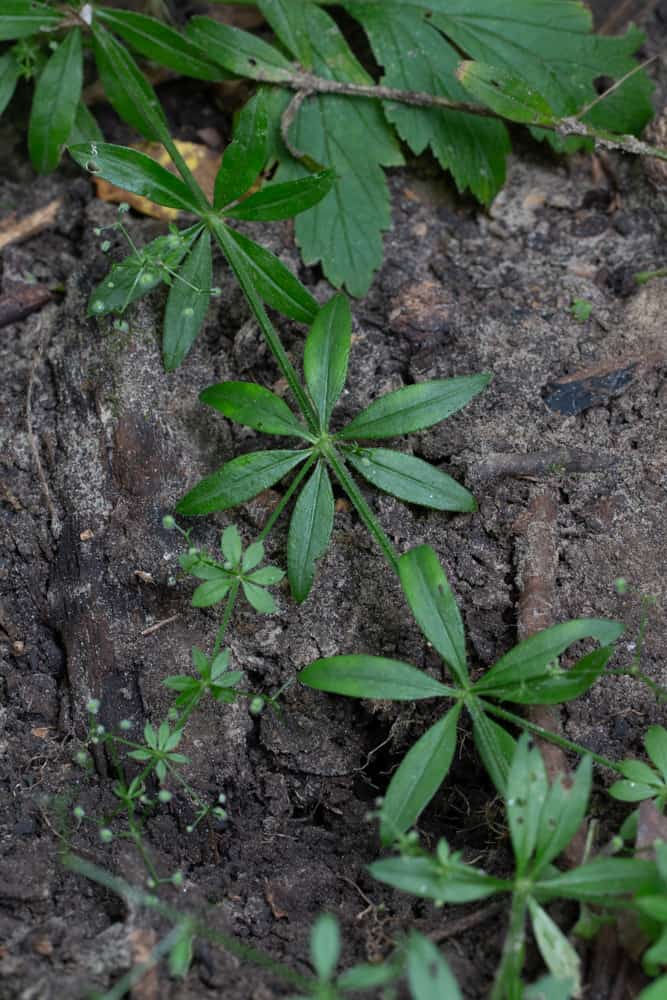

At first glance, it was difficult for me to separate Galium triflorum from other related cleavers. But, compared to other galiums, Galium triflorum:

- Has more oval-shaped leaves, ending in a delicate point.

- The smell, although less-distinct fresh, is a dead giveaway. It does take some time to get to know it in the field though, and it's easy to confuse with Galium asparellum.

- If you harvest the wrong plant and dry it, and it smells like nothing, or just grass clippings, you picked the wrong galium. Once it starts to dry, the aroma is unmistakable.

Harvesting

Galium triflorum is so prolific in some areas that large amounts can be gathered quickly, but, in the right place, at the right, time, you can get even larger amounts of the plant. Typically I see it in semi-shaded deciduous woods along trails, but it also grows in coniferous woods in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

In areas of the farm I live at in Wisconsin that have been logged, the removal of the tree canopy increased the growth of the plants exponentially, and I've harvested plants multiple feet in length, growing vertically, instead of prostrate/on the ground. Like sweet woodruff, the aroma will be strongest later in the season as the plant matures and begins to flower, a coincidence I can only assume is a natural way to attract pollinators.

Processing

After I harvest the leaves of the plant, I dry them. The leaves and stems are long and unwieldly, so I find it helpful to tie them into bundles before putting in the dehydrator. The plant dries quickly and efficiently, and should be done drying in 24 hours at 100F. After drying, I pack the bundles of leaves into bags and store in a pantry, or use them to make wild vanilla extract.

Cooking

Using the fresh or dried leaves

Cooking with the plant couldn't be easier, and it's potent aroma means that you only need a small amount to flavor things. While I typically use the plant to make my wild vanilla extract, it can also be used fresh or dried. A great way to get a feel for how it works is to use it to infuse a panna cotta.

Put a small handful of dried leaves in some cream, warm it and allow to infuse for a few hours or overnight, then strain and proceed as you would for a typical panna cotta. The possibilities are really endless with this plant.

Using the extract

Typically I use the plant as an extract. It can be substituted nearly 1:1 for commercial vanilla extract.

How to Make Galium Triflorum Vanilla Extract

Equipment

- 1 Pint mason jar

Ingredients

- Dried galium triflorum or sweet woodruff leaves Enough to pack two quart mason jars full

- Vodka Enough to cover the leaves

Instructions

- Pack the jar with dried galium leaves, pressing them down a bit to really get them in there.

- Cover the leaves with vodka, screw on a lid, and allow to rest in a cold dark place for at least two weeks. Remove the leaves, squeezing them dry, strain the liquid and store in the refrigerator for the best flavor, although it can also be stored at room temperature.

- For a stronger infusion, remove the leaves after 30 days, squeezing them dry to get as much as possible, then add more dried galium leaves back to the jar until they're submerged, pressing them down firmly. Allow the jar to rest another two weeks, or longer, then repeat the straining process and store until needed.

- Use the finished extract in larger quantities than typical in baked goods (1.5-2x what you'd normally use) and roughly as a 1:1 substitution in dairy-based desserts.

Notes

Related Posts

Wild Szechuan Peppercorn (Prickly Ash)

Linh

Do you have any experience with galium odoratum in this capacity?

Alan Bergo

Yes, I actually find G. triflorum stronger in aroma than G. odoratum.

Brian

hey Alan, what difference (if any) would you say there is between woodruff extract and vanilla?

Alan Bergo

Woodruff and friends have a grassy note to them. Imagine driving down an old country road and smelling fresh cut hay-it's the same compound going into the air as clovers etc contain it too.

Brian

thanks! would you say there are any particular recipe types where you feel like that flavor really shine over normal vanilla? woodruff is ironically harder for me to come by than vanilla extract

Alan Bergo

Man I struggle to think of things it isn't good in. This week I made duck egg brownies with a splash and it was great. I also used it in panna cotta last week, and in a batch of black walnut milk I made this morning. Any sweet baked good really, but especially anything containing dairy, or a fatty liquid.

Skincollector

In Germany we make Götterspeise ( food of gods) also called Wackelpudding ( wigglepudding) out of sweet woodruff (Waldmeister). Which is topped with a vanilla sauce.

It’s very popular amongst children specially as a chilled summer desert 🙂

Alan Bergo

Hey thanks so much, I'm adding this to my list of things to try with the plant. Really appreciate you sharing that!!

Eliza Z

I came across this article, while looking for a local herbal substitute for vanilla. I use Galium triflorum in my formularies and for some reason never thought of using it as a vanilla substitute, thank you.

You mention double infusion for a stronger batch. Have you tried using 190 proof Sugar cane alcohol for pulling the constituents? You would only need a 2 week period of letting it sit, plus breaking down the mark to smaller size before making the tincture would also provide room for more plant matter to be used.

Thank you again

Alan Bergo

Hello Eliza. I haven't done a stronger batch using different alcohols, but, as the compounds are very alcohol soluble, I'd imagine it would work well.

Darrin

In your book you call for brandy instead of vodka. Do you recommend one over the other? Would other booze (bourbon) work?

Alan Bergo

Bourbon would be great.

Scott H

I planted sweet woodruff in the shade of my carport a couple of years ago after I had a friend's may wine. Really looking forward to trying this out!

PS Looks like your link to Monica Wilde's post is incorrect and should be: https://monicawilde.com/is-sweet-woodruff-poisonous/

Alan Bergo

Thanks I adjusted that link.

Ann Pilcher

Hi Alan, If I understand correctly, it sounds like you dehydrate the plant with the stems on. So, to make the vanilla extract, do you remove the dried stems before combining the dried leaves with the vodka? One more question....when is the best time, in the plant's growth stage, to harvest it to in order to get optimum flavor?

Alan Bergo

Use the whole thing stems and all. The plant is so powerful it can be harvested at any time. That said, it will be the strongest when it's flowering or getting ready to attract pollinators.

Ann Pilcher

Hi Alan, If I understand correctly, it sounds like you dehydrate the plant with the stems on. So, to make the vanilla extract, do you remove the dried stems before combining the dried leaves with the vodka?

Seth

Hi Alan, thank you for all of this wonderful information! I just purchased your book from my local bookstore, and I can't wait to pick it up once it arrives in the shop. For using sweet woodruff, is the drying process necessary or can fresh leaves be used instead? I unfortunately don't have a dehydrator on hand, although I could use an oven. If you've got any suggestions for how to properly dry the leaves in the oven, I'd be tremendously grateful for any guidance you might have!

Alan Bergo

I can't legally recommend drying this plant without a dehydrator for safety reasons, but, if you wanted to I would hang plants up and put a fan on them for a couple days until brittle and that should work.

Lori Tummonds

This post, and your post on wild vanilla extract, are brilliant. Thank you!

Alan Bergo

Thanks Lori