Little known outside of Italy and Europe, chestnut flour (farina de castagne) has been a staple crop in Northern Italy for thousands of years. At roughly four times the price of wheat flour it's a very special ingredient worth getting to know. Today we'll go over what it is, how homemade flour differs from store-bought, and how it can be used in recipes.

I knew chestnut flour could be purchased, but I didn't truly understand the historical significance until I visited Tuscany last year. Chestnut trees were everywhere near Radicondoli where I stayed.

In the fall the locals gather the nuts and bring them to a processor who dries the nuts over a wood fire, slowly smoking the nuts for weeks until their dry enough to shell and grind into flour.

In my kitchen there was a 50 lb sack of the flour in the pantry, at about 55 cents an ounce that's a roughly $450 bag of flour. Opening the bag like a kid on Christmas morning, a scene like The Amityville horror unfolded as legions of weevils escaped from the bag (which I disposed of, sadly). Needless to say, the first thing to know is that chestnut flour should be refrigerated or kept in the freezer to ward off insects and mold.

What is Chestnut Flour?

Just as it sounds, chestnut flour is made from the ground, dried seeds of the chestnut tree, known in Italy as "Alberi di Pane" (bread tree). Commercial chestnut flour is made in Italy from species of sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) but it can also be made from American chestnut (Castanea dentata). As American chestnuts are extremely rare, most foragers in North America harvest from hybrid trees mixed with Chinese genetics.

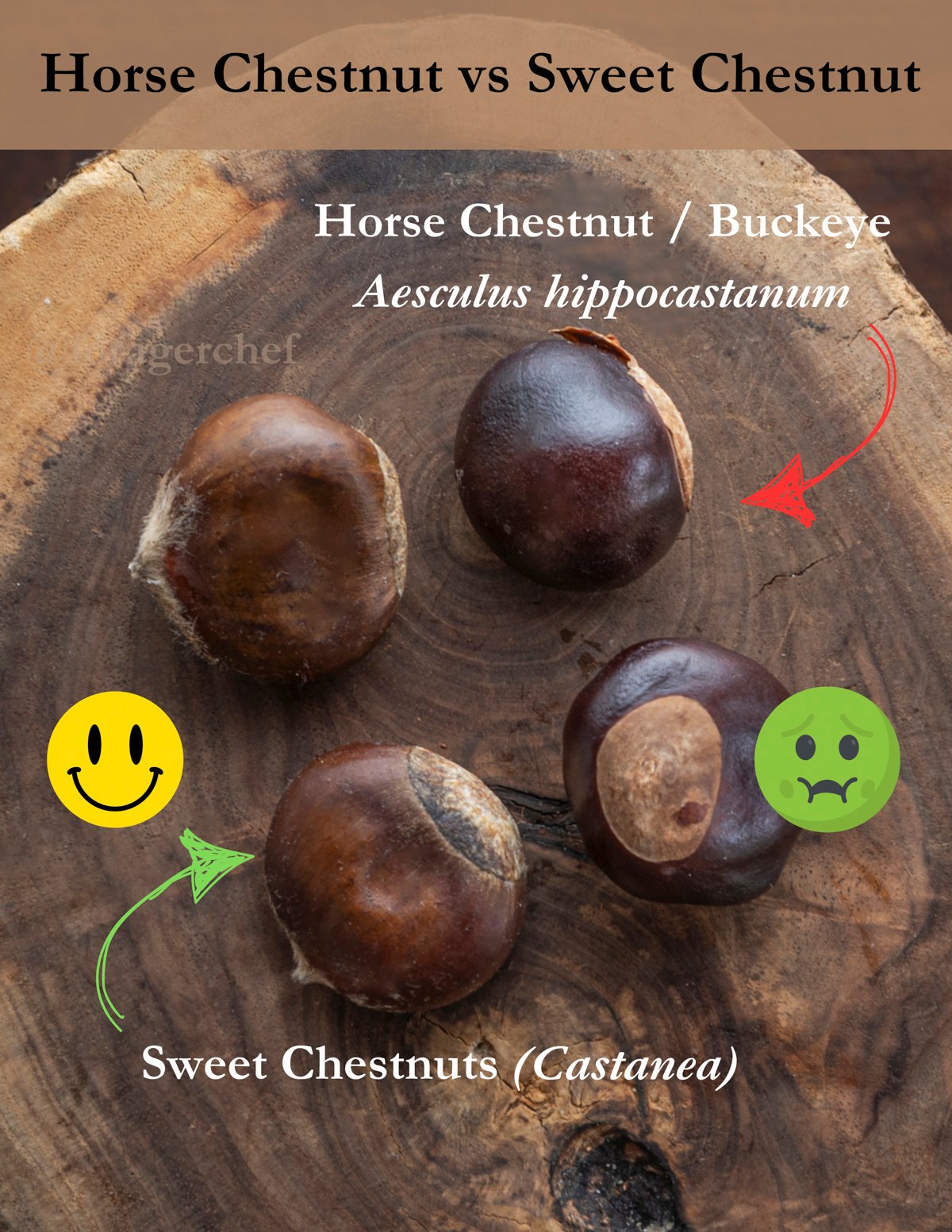

If you harvest your own chestnuts you'll need to be able to distinguish them from bitter horse chestnuts, also known as buckeyes (Aesculus hippocastanum).

The most interesting fact to most people is that chestnut flour is essentially the original polenta. Polenta is made from ground corn, but corn is a New-World ingredient that's only been known in Italy for about 500 years.

Before corn came to Europe there was chestnut polenta, or polenta di castagne, with corn eventually taking its place. Chestnut flour is still produced, but the end product is quite different from ground corn.

How to Dry Chestnuts

Before making the flour the chestnuts must be dried. I've had success simply leaving the nuts out on a tray with a fan on them, but it's important to have good air circulation to prevent mold.

Left to dry on a tray with a fan blowing on the nuts they'll be dried in 1-2 weeks. The fastest way to dry chestnuts is to use a dehydrator which takes 3-4 days. Since the nutmeats are large, drying the nuts in an oven isn't very energy efficient and could potentially burn them.

If you really want to stay close to tradition, you could smoke the nuts in a pellet grill on the lowest heat setting for a day or two before transferring to a tray with a fan. Once the shells are bone dry the nuts can be cracked and ground.

How to Make Chestnut Flour

First the chestnuts must be cracked. The shells are brittle after drying and easily cracked with a mortar and pestle, hammer, or even by hand. To crack large amounts of chestnuts at once they can be put in a gunny sack and hit with a rolling pin or another blunt object. Any remaining test (the inner, brown fuzzy skin) is removed to prevent the flour from being bitter.

There's even electric chestnut crackers you can buy, but as the shells are the easiest to crack of any nut I've cooked I hardly think they're necessary unless you have a commercial operation.

After cracking the chestnuts are ground. As the nuts are too large for a mill I crush them in a mortar and pestle (molcajete) first to break them up. Once the nuts are broken into smaller pieces they can be ground in a grain mill or in Vitamix dry bowl.

After grinding once the flour should be sifted, with the larger particles ground and sifted again.

I've had the best results finishing my flour in a spice grinder, but even then it's not as silky smooth as the commercial flour.

How to Use Chestnut Flour

Generally speaking, the flour can be added to breads and doughs, cooked into a polenta-like porridge. As it's naturally sweet, it's great added to baked goods like cakes and pastries. While I was in Tuscany I served chestnut brownies made with ½ chestnut flour and chopped roasted chestnuts. They're to die for.

Since it contains no gluten, if you're making bread you'll want to add no more than 30% of the total weight of flour to ensure it rises properly.

Homemade vs Store-Bought

The chestnut flours I've purchased online are velvety smooth with a texture like powdered sugar. Cooking with them reminds me of Korean acorn starch in that it absorbs less water than cornmeal.

The flour I make at home is more coarse and is noticeably less sweet, likely due to a sweeter variety being used to make the commercial flour. For most purposes, the finer you can get your flour to be, the better it will perform.

Homemade flour is best for things like polenta, or adding to wheat breads or quick breads. As it's slightly less sweet, it's also easier to serve with savory dishes. Commercial flour is what you'll want to make pasta and the famous necci (pancakes / crepes), pasta and gnocchi as they can be brittle made with homemade flour.

In short, homemade chestnut flour can be used in recipes calling for cornmeal, and smooth commercial flour can be substituted for all-purpose flour.

Chestnut Flour Recipes

There's a number of traditional recipes using chestnut flour which can be savory or sweet. Any of the sweet recipes pair perfectly with chestnut honey which has a rich, unique flavor. The polenta and crepes can be made with homemade flour, but to make the pasta and gnocchi you'll very smooth Italian chestnut flour.

Probably the easiest to make, these are simply crepes. Naturally sweet, they're traditionally served with ricotta cheese filling but can also be used like cannelloni pasta tubes or in any recipe calling for crepes.

While it might sound like a dish dish to serve with ragus or braised meats, the natural sweetness of the nuts puts the polenta firmly in the sweet realm unless mixed with cornmeal.

It's traditionally served with ricotta, and makes a delicious, filling meal for breakfast, brunch, or light summer dessert. Smooth as velvet, nutty and sweet, the cooled slices drizzled with chestnut honey and ricotta cheese is novel, delicious, and addictive.

One of the most interesting recipes I've made over the years as it defies the conventional 30/70 rule of how much wheat flour can be diluted by alternative flours. Up to half of the wheat flour can be substituted with chestnut flour.

While you could technically make fresh gnocchi with a puree of nuts mixed with potatoes, the traditional dough is simply a pasta dough. Just like potato gnocchi, the dough is rolled into ropes, cut into pieces and rolled off a gnocchi board or the tines of a fork to give them the traditional ridged appearance.

They have a firm texture of pasta and the subtle sweetness means they pair well with wild game like boar, duck and venison.

- Castaggnaccio, Cakes and Breads

The most famous dessert besides the Monte Bianco (made from a puree of fresh nuts) is Castagnaccio, a sort of firm, hard cake studded with grappa-soaked raisins and flavored with rosemary and orange peel.

There's also regional variations nearly identical to the acorn flour torte in my book which is leavened with whipped eggs pictured above. Chestnut flour could be substituted for a similar, slightly sweeter effect. There's a link to my recipe below.

Related Posts

How to Make Chestnut Flour

Equipment

- 1 High speed blender or grain mill

- 1 mortar and pestle

- 1 Fine mesh sieve or flour sifter

- 1 Spice grinder

Ingredients

- 4 lbs Fresh chestnuts

Instructions

- Put the chestnuts on a dehydrator tray and dry on medium heat (90F) for 3 days or until bone-dry. Drying chestnuts at a higher temperature can cause them to turn black.

- Alternately the nuts can be dried on a tray with a fan blowing on them, they may take over a week to dry like this.

- Crack the chestnuts and remove any inner brown skin, which can make the flour bitter.

- Crush each chestnut with a hammer or in a mortar and pestle to make them easier to grind.

- Put the cracked chestnuts in a Vitamix dry bowl or grind with a grain mill.

- Grind the flour a second time in a spice grinder, then sift through a fine sieve to remove large particles.

- Grind the leftover pieces a second time, sifting and repeating to get the finest flour possible.

- Store the flour in a jar in the refrigerator or freeze for long term storage.

Joan

Follow up question, just to be extra real - how thoroughly (or not) do you worry about getting weevil larvae out of your dried nutmeats? Like if the nutmeat is beautiful and yellow with just the little white tunnels of (presumably) frass, do you leave it? Vs holes/tunnels that caused darkening or actual rot of the nutmeat? Where do you draw the line?

I harvest twice a day right now, and sort nuts into choice (for drying, no visible blemishes) and cook first (blemished/audible larvae or hints of mold on shell). But that doesn't magically prevent there from being tiny larvae in the choice nuts.

So - I'm curious if you prioritize a particular step/process/timing with the aim of killing the larvae faster to preserve as much nutmeat as possible, or if you just plan on a certain percentage of loss and do a lot of trimming or toss any 'infected' nuts. Thanks for reading & whatever you may choose to share.

Joan

We're deep in Chestnut season here in central Virginia - idk when they ripen in MN, but I'm crossing my fingers that we might get to see some Chestnut content from you in the next couple months. (Idk why my phone auto capitalizes Chestnut but I think it's funny so I'm leaving it)

If you do any new Chestnut posting this year, could you share more detail about drying? Most other sources I'm finding suggest 3-7 days, saying that chestnuts dry faster than other nuts, being less fatty. Are there any qualities you can point to that indicate adequate dryness for you? Or any signs that they need more time?

I've only done acorn flour before, which is so different with all the leaching that I don't have any kind of even vaguely similar point of reference.

As a bonus if you're feeling verbose - my partner is drying Chestnut flour from boiled and/or roasted nuts. Do you have any insights as to the value of drying & grinding uncooked nutmeats vs grinding freshly cooked ones?

As a hide tanner, I generally navigate these kinds of questions from a zoomed-out process perspective - people often ask about steps that are only necessary based on particular conditions, or needing to store something safely for a stretch of time. I'm curious how much of that applies to what I'm generally reading about chestnuts - e.g. Is the point of drying to have shelf stable in-shell nuts before being ready to make flour? Or does it fundamentally change your end product regardless of storage time or method?

Thanks for whatever additional level of depth/complexity you feel inspired to share this year. & if you know someone else has already covered this ground somewhere I can actually read, please feel free to just redirect me. I've been searching up a storm, but when most websites are 70% ads and deeper content is often buried in nigh unsearchable social media, it's hard to know where to look.

Thanks for reading

Alan Bergo

Hello. I’ll answer as best I can here.

The nuts are properly dried when they’re bone dry, brittle, and able to be ground into flour. 3-7 days should be fine depending on your setup. A dehydrator that uses heat will drastically speed up the process vs air-drying with a fan. But, if you have large amounts, it could take a week or more if you’re drying on a speed rack with a box fan or something similar.

When properly dried they should rattle in the shell and the shell should crack without much resistance.

I’m currently in the throes of writing a new book and have no chestnut content on deck. Plenty in the freezer, hopefully next year. The book is a massive project and I get requests for content on dozens of species each year. I do my best.

I can’t provide any insight into nutritional aspects of anything. As much as I would like to sometimes, I stay in my lane as it’s beyond the scope of my training and study.

The nuts are dehydrated to preserve them. That said, I still keep dried chestnuts in the freezer as fat will eventually go rancid, a good example being hickory nuts.

If the chestnuts are dried and not shelled they could likely keep for months in a root cellar.

If you’re already sorting your nuts by quality then weevil damage is not really an issue. Especially if the nuts are just ground to flour. I do like to separate them by quality, but that usually means perfect ones are roasted, boiled and eaten as opposed to grinding into flour, which is what the “B-grade” nuts are for.

Happy harvesting.

Joan

Thanks so much, Alan, especially for a generous, thorough, & Fast answer in the midst of such a big project.

We're currently drying in a closet with a dehumidifier and box fan, as it's so humid here that drying in the open is a real challenge. The dehumidifier creates some heat, so it's generally in the high 70s/low 80s inside.

Thanks again. I'll keep experimenting.

Alan Bergo

hanks Joan.

Richard Stevens

You need one of these: https://willitgrind.com/

Alan Bergo

Thanks Richard I'll take a look. Seems like a nice machine at a glance.

Michelle

😋 We love chestnuts! Today my kids and I roasted some over our open fire (thanks to a cast iron griddle from the stove 😅 We’re in the process of moving to a homestead, and it really made me want to install an open hearth for cooking!). Last winter I made a soup with chestnuts puréed into it - I’m thinking it was a butternut squash soup - it was so good. I read The Good Left Undone recently and - if you haven’t read it - it mostly took place between WW2 era Italy and modern day Italy, but there was a comment about being surprised at people loving chestnuts today because they were a survival food during the war. Thought that was interesting.

Michele

Hi Alan,

Thanks so much for another great post. I once had a gluten free sourdough chestnut bread that was to die for. Have you ever tried making a sourdough starter with the chestnut flour, or a GF bread with it?

Alan Bergo

Thanks Michele, I've been working on it for months. The video version is coming this week. I wanted to wait until the week the fresh chestnuts hit the shelves to share it.

On the bread, there's some good gluten free flours available on the market now. I just got a bag of Antimo Caputo that's GF, but's supposedly able make regular breads and doughs. It's really spendy. If I was going to add chestnut flour to a bread made with a GF bread flour mix that can be substituted in sourdough recipes, I'd start with the same ratio (no more than 30%) of the chestnut flour to GF flour. Also a company in the Twin Cities makes the best sourdough GF bread I've had, and they ship. They seemed protective of their baking process with me, but you can learn a few things from just inspecting a loaf, and it's really good.

ollie

Alan Bergo November 23, 2024 at 10:35 am

Thanks Michele, I've been working on it for months. The video version is coming this week. I wanted to wait until the week the fresh chestnuts hit the shelves to share it.

On the bread, there's some good gluten free flours available on the market now. I just got a bag of Antimo Caputo that's GF, but's supposedly able make regular breads and doughs, really spendy.

HELLO there. Proof your paragraph up there, eh. Cheers!

Alan Bergo

Thanks for the copy edit.

Carla Beaudet

Oh, thank you, thank you for the inspiration here. I had the pleasure of visiting a couple of high altitude chestnut forests in the Appenines of Tuscany about a month ago. The trees all were like huge stumps with a number of ~12" diameter shoots coming out of them. It was explained that the stumps were ancient, some on the order of 1000 years old, and the shoots were the result of repeated copicing and in some cases, grafting. I was impressed with the effort of that silviculture, on those incredibly steep slopes. We were there with a permit to forage mushrooms (the porcini grow in mycorrhizal relationship with the trees), not chestnuts, but the ground was literally covered with them, and much like you explore here, it was clear that, for generations of people living in these mountains, this WAS flour, what you make bread with. I have foraged chestnuts from the handful of trees I have access to here, but after shelling and removing the test (thanks for that vocabulary word!), I generally grind them to meal, or to a paste with sugar and a little water to use for dessert applications. And yeah, freezer storage for shelled tree nuts in general. Even if it weren't for the weevils, the oils go rancid in less than 6 mo. I am not sure your inspires me to make chestnut flour, but I will certainly be looking to these beautiful recipes to play with the commercial chestnut flour that can be found online. I do have questions about your process for flour, but I'll direct those to you in email because it's too long for the comment.

Alan Bergo

Hey Carla. I'm jealous you got over there while there were mushrooms. The only mushroom I found was a Boletus satanus. Yes, homemade chestnut flour is kind of a novelty compared to the ultra fine commercial version, you can make the necci pancakes with it but it's impossible to make pasta dough that will hold together. I definitely recommend buying commercial flour to start as it's easier to work with.

Carla Beaudet

The Necci are what I'd like to try, but the link isn't working for some reason.

Alan Bergo

That’s odd, I just double checked and it’s working on my end. I’d try refreshing the page.

EC

Again, I learn something new and fascinating from you! I love chestnuts, but had no idea they could be made into flour, or used for anything like the above recipes. Thank you!

EC

Hmmm, where oh where could that brownie recipe have gone? I'm not normally a fan of brownie's, but these look amazing, and the contents even better!

Alan Bergo

It's good but I'm not quite ready to post it, still working some kinks out of it. I need to increase the cooking time or add an additional egg to help them hold together a bit better. When I was in Italy I substituted 1/3 of the flour for chestnut flour, but IMO it's not enough chestnut flour to be notable. I'm making them again for deer camp this weekend and hopefully I have a dialed in version. I'll ping you here when I get it up.

EC

Take your time to get it how you want it, and I will be patiently awaiting your ping, lol. In the meantime, I am saving the picture...🤣

Terry

I'm waiting for these as well! I have an American and a few Euro chestnuts just beginning to bear. So many good ideas, as usual. I will use the commercial flour first before I start fiddling with mine. Thanks as always, your weekly posts are something to look forward to!

Alan Bergo

Thanks Terry

Tony

You should probably warn people that Horse Chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) is not the same thing as American chestnut (Castanea dentata). The nuts look very similar but Horse Chestnuts are toxic.

I have a friend who was once served "roasted chestnuts" at Christmas time. Then the host proudly announced that he had gathered the nuts himself! American Chestnut is almost non-existent in MN. The nuts turned out to be Horse Chestnuts. The whole dinner party had to go to the hospital and get their stomachs pumped.

Alan Bergo

HI Tony. I added an infographic I had in my files. You might find it interesting to know that horse chestnuts are *technically* edible after processing and are a traditional food in Japan. My friend wrote a book on traditional Japanese wild foods describing the process.