Behold the mighty burdock: a plant that looks like rhubarb, was the inspiration for velcro, and is a traditional food known in Asia likely dating back millenia. Most foragers know gobo / burdock is edible, but only a few people in my circles could describe how to prepare every edible part. Today we'll go over everything you need to know about foraging and cooking burdock root, flower stalks, and leaf petioles.

What is Burdock?

Burdock (generally Arctium lappa and Arctium minus) are massive perennial plants native to Europe and Asia. They're in the Asteraceae family making them related to dandelions, sunflowers, and artichokes.

The plant is a common invasive weed that loves disturbed areas like the edges of farm fields, trails, vacant lots, yards, and really anywhere it can get a foot hold. Sometimes it's mistakenly called wild rhubarb.

Generally speaking, there's two species of burdock plants you might come across, with one being more common than the other, at least where I live. Arctium minus (lesser burdock) is the most common plant I see.

Arctium lappa (greater burdock) is less common, and absolutely massive in comparison to it's sibling, as you can see below. There's also wooly burdock (Acrtium tomentosa) which I have yet to meet.

In Asia, greater burdock (known as gobo root) is cultivated as a vegetable, and sold at nearly every Asian market I've ever been to. Some farms in the Midwest will harvest and sell lesser burdock, but the roots are smaller, uneven, and slightly tougher. Confusingly, when I see lesser burdock sold in local coops it's expensive, around $8/lb, where Asian markets might sell it for about $2/lb.

Burdock Identification

The plant starts as a basal rosette, developing an extremely long tap root that can be multiple feet long.

The leaves are felt-like and wooly on the underside with light-colored, fuzzy veins.

Sometime after the first year of growth the plant will go to seed, then die. Although I've referred to it as a biennial for years, that's incorrect and it's technically a monocarpic perennial, so this could be year two, or three. The final stage of growth begins with the towering flower stalk appearing in late Spring that might grow be five to six feet high.

In the fall the plant creates the seeds I grew up calling cockleburrs which will stick to any and every article of clothing you have. That part of the plant, specifically the interlocking hooks, was the inspiration for velcro.

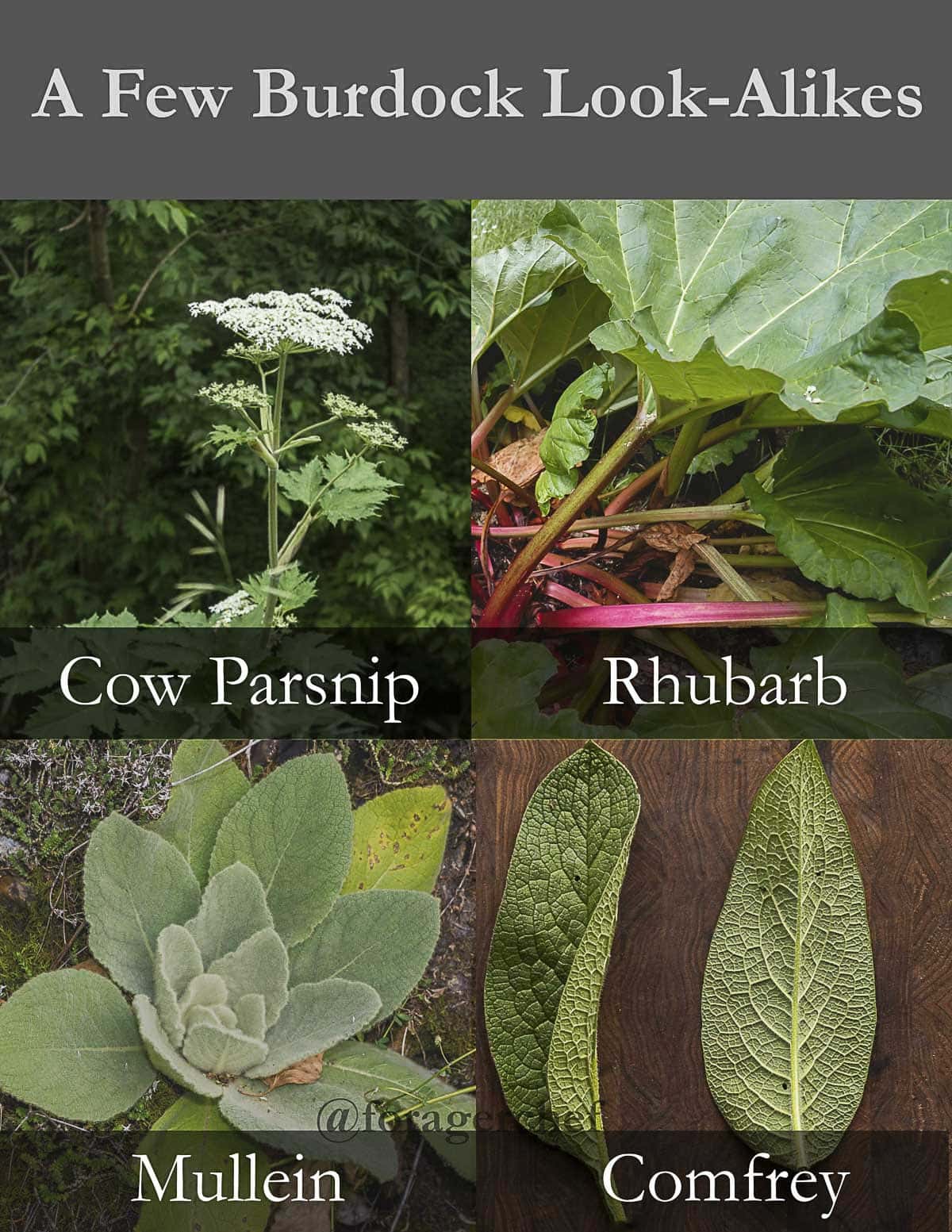

Burdock Look-alikes

Generally, I think of burdock as one of the easiest groups of plants to recognize, but I still get emails asking if it's wild rhubarb every year.

For most foragers this may be a bit of a stretch, but there's a few plants I could see people confusing with burdock. As far as the leaves go, comfrey is probably the most similar I can think of besides rhubarb, but it has purple flowers, is perennial, doesn't appear in a basal rosette form, and established plants are usually only a couple feet tall.

Other plants that vaguely resemble burdock might be mullein and cow parsnip. All of the aforementioned are edible in some form or quantity, although rhubarb leaves are toxic and the leafy green parts of cow parsnip contain phototoxic sap.

Edible Parts of Burdock

The root is by far the best known part of the plant that's eaten but the the flower stalks and leaf petioles are also edible. I'll cover them all briefly.

Root

If you've ever tried to dig a burdock root and found it nearly impossible to unearth, you're not alone. If you don't buy the roots at an Asian grocer you need to know how to dig them, or with my method, dig as much as you can, as easily as you can.

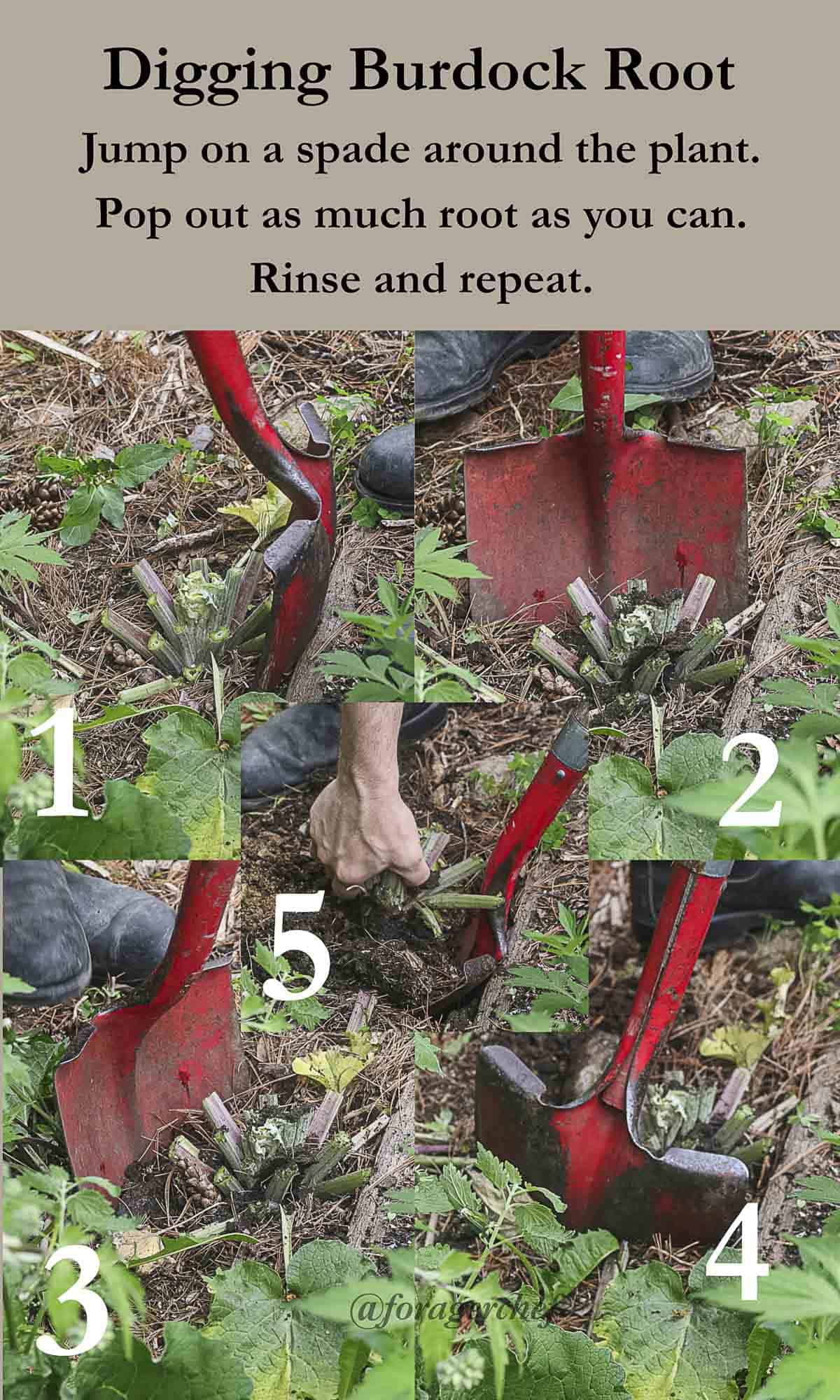

How to Dig Burdock Root

Just like other roots (horseradish, parsnips, etc) burdock should be dug in the spring or fall when the plant is dormant.

Over the years I've developed a method I like to use that works for me. The key is to forget trying to remove the entire root. It's difficult to show the process in images, so I'd encourage you to watch the video at the end of this post I've been piecing together over the past few years.

Not trying to remove the entire root means you'll get less per plant, and the top portion isn't quite as good as the deepest portion. But, as large rosettes can produce top chunks of roots weighing eight ounces or more, I find it much more efficient than the alternative. I've harvested about twenty pounds in an hour this way.

It's also best to look for plants that are growing in soft, rich dirt. If the roots hit rocks they can split, giving you thin, spindly roots that are hardly worth the time it takes to clean them, as you can see below. I also jump at the chance to dig roots after a rain as the ground is softer.

Cleaning and processing

After harvesting the roots should be washed and stored in the fridge where I've had them last for a couple months. I like to keep them in a hard-sided polycarbonate restaurant container, but you can also store them wrapped in a thick towel. They'll dry out stored in a paper bag.

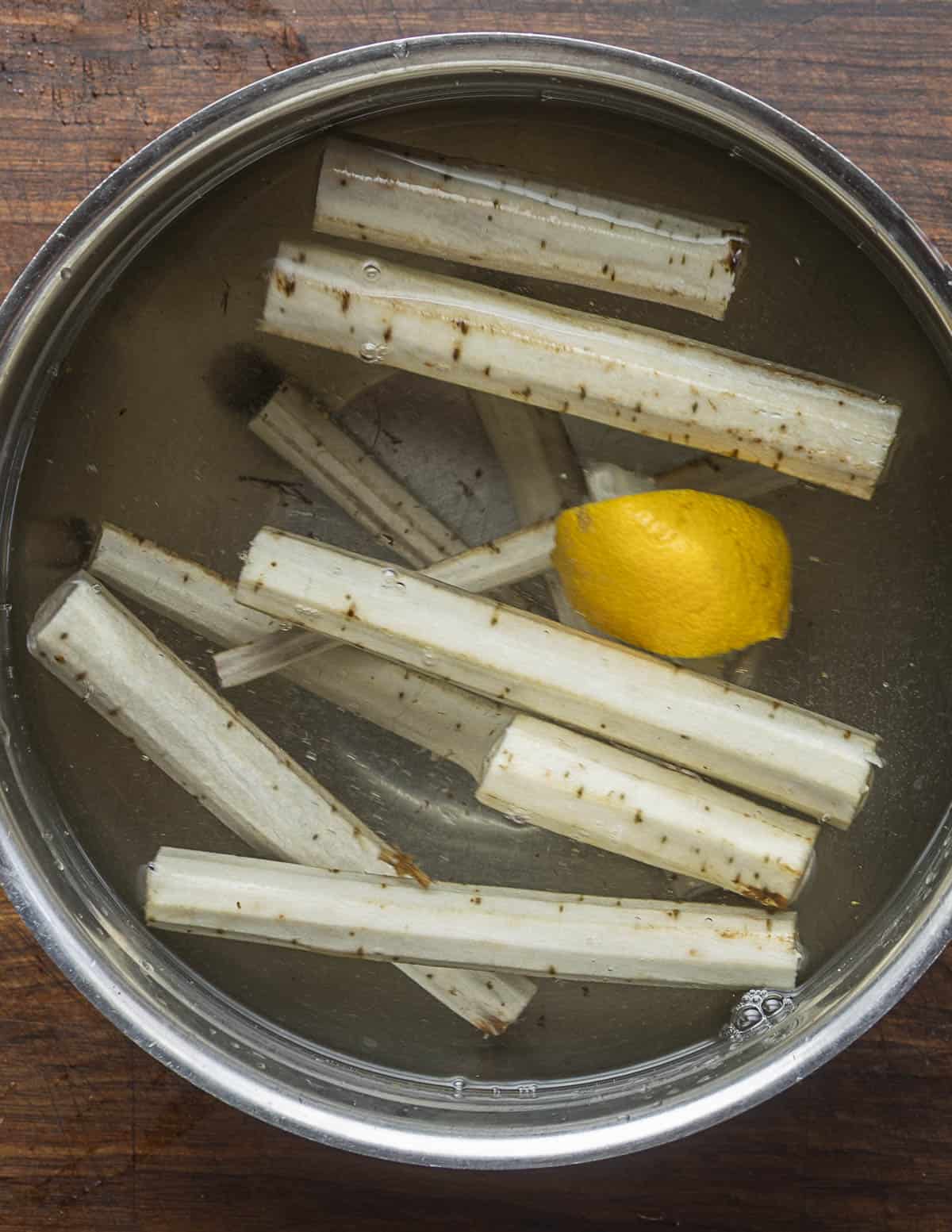

When you're ready to process and cook the roots, they should be trimmed, peeled and held in acidulated water to prevent discoloring. Once again, a Y-shaped Kuhn Rikon peeler is your best friend here. I learned the hard way not to soak the roots overnight as they'll curl.

Cooking Burdock Root

Paying attention to tradition is important here. While you can cut the root into other shapes, where the root is a traditional food it's typically cut into julienne and stir-fried.

Cutting the root into thin strips transforms the texture from woody to pleasantly chewy-it's genius. Below I'm making kinpira gobo, which is probably the most well known Japanese burdock root recipe, but it's also cooked by itself as a banchan (Korean side dish) among other things.

Leaf Petioles

Probably the least used edible part of the plant, I'd heard rumors that the leaf petioles (stems) were edible but found it hard to believe as they're intensely bitter and stringy.

It's true, and the best cultural reference I have here is reputed to come from Italian immigrants who mistook the plant for cardoons, calling them "garduni / carduni". After cooking they have the texture of bland, boiled celery.

To cook the petioles, it's important to harvest them before the flower stalk begins to rise from the center of the rosette-otherwise they'll be like eating dental floss. More established plants are also preferable here as the petioles are thicker, as shown above. If you find petioles thick enough to peel, they might even be good! Here's the process.

After boiling until very tender, the petioles are drained and typically made into "garduni fritters". The process is similar to my wild fennel cakes and I'll have a recipe for them in my next book.

Leaves

Burdock leaves are technically edible, but are intolerably bitter. But, they can be used as a natural wrapper for meat during cooking and the bitter compound on the leaves doesn't transfer to the food. This is a novelty for me, and the fuzzy leaves make a better emergency toilet paper than food.

Flower Stalks

The finest part of the plant is the flower stalks, and this is the last harvest which happens in late spring around the beginning of June in Minnesota. In one afternoon in a good patch I've harvested over 100 pounds before processing when I was supplying restaurants.

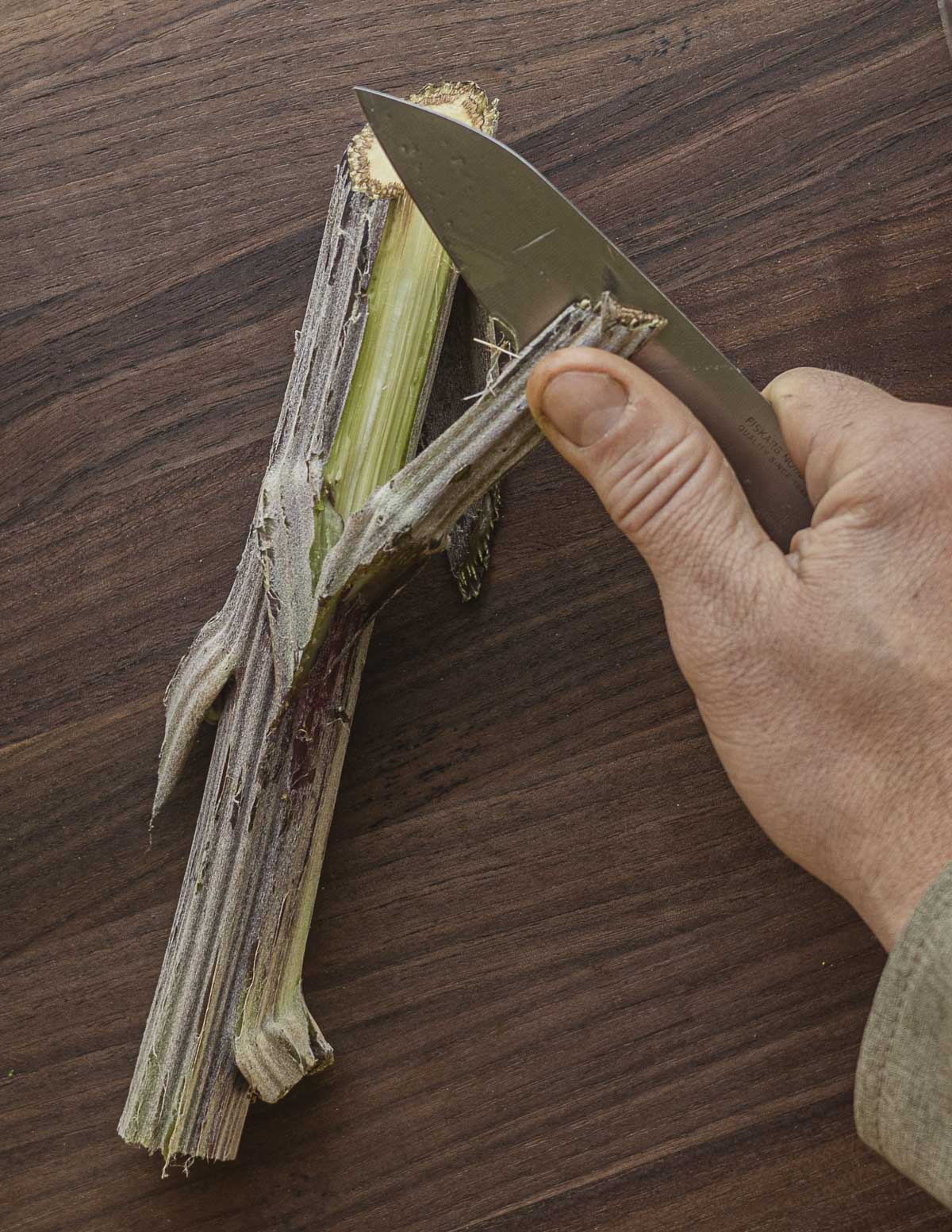

Just like the petioles, it's important to pay attention where the plant is in the growing cycle.

You want to harvest flower stalks before the immature flower heads form (see above) and the leaves have completely filled out. The images below describe the basic preparation.

After the stems are cooked tender they can be browned like salsify or cooked in vegetable medleys. Their best use might be as a soup vegetable, where you can just toss a handful into the pot while it cooks without blanching. can also be cooked directly in soup, as I described in my first book, Flora. Here's a few dishes I've made with them over the years.

Tamidon

How long would the flower stalks last, unprocessed, in the fridge held like the roots? I have a lot, more than we could eat in one go. Also, blanch and freeze and option?

Alan Bergo

The stalks will last for weeks.

Joanna

This may have to be the next thing I try! I got your article last month about linden leaves and I had a lot of fun eating the buds and using the leaves like spinach.

Thank you 🙏

Carla Beaudet

I had given up on wild burdock (but not on burdock root from Asian groceries, which I either pickle or use in kinpira) until I followed Sam's advice and tried the peeled young flower stalks. The centers of these stalks have all the flavor but none of the fiber of the roots. Superb! The following year, I harvested a bunch of stalks that were 3'- 4' tall....and there was nearly nothing inside:-(. I'd waited too long. It's important to get these early. Now is about the latest...and I haven't found any this year. Will have to make a concerted effort. On the upside, I have harvested a bunch of cow parsnip buds, and will try them tempura-style as you have suggested. Also, and I give this away because I am uninterested in blogging, I have found that the best way to mitigate the strong flavor of cow parsnip is by treating it like angelica - I candies the leaf petioles, and that not only made them tasty, but also produced a syrup that begs to be used in a cocktail, maybe with gin?

Margie

Thank you chef , you are so inspiring. Thank you so much for explaining everything in a way that is simple to understand. I have never tried burdock but I remember it growing in my St Paul alley by the neighbors , now I am in Arizona foraging my cactus !

Alan Bergo

Thanks Margie. Makes me think of barrel cactus buds. I also get lots of Asian mustard greens in the spring near PHX. Grandparents live sown there.

peggy

thanks. I love your work. wish I could follow and forage.

Alan Bergo

You’re so welcome Peggy.

MARIE Forbes

Many years ago I practiced Macrobiotics for about 7 years having taken cooking classes at the Kushi foundation in Brookline with Wendy Esko and taking yoga classes with Bo In Lee, Lee Sensei. At that time, I would buy the burdock root at Erewon and make a dish with tofu, brown rice, carrots, onion and burdock. Even my little twin daughters loved the meal topped off with a cup of miso soup with wakame. I now realize that I have burdock growing outside my garden at the Weston Community Gardens! As soon as it stops raining, I'll grab the shovel! Thank you so much for this wonderful and useful information!l

Lisa

I love this article. Burdock was my first wild edible and medicinal ally and I still love it. I appreciate this very thorough information, thank you! Your book is so excellent and I can’t wait to use the techniques I’m learning from you!