Sumerian pigeon soup is a love letter on pigeons being worthy for the table, and an example of how I get inspired by historical texts. I like variety, and my collection of food references spans everything from Greco-Roman Apicius, Archestratus, and Byzantine Geoponika, to the more modern A Discourse of Sallets and The Little House on the Prairie, to name a few favorites. I love all my old books, and each is a useful lense for looking at food in it's own way.

Sumerian pigeon soup is a love letter on pigeons being worthy for the table, and an example of how I get inspired by historical texts. I like variety, and my collection of food references spans everything from Greco-Roman Apicius, Archestratus, and Byzantine Geoponika, to the more modern A Discourse of Sallets and The Little House on the Prairie, to name a few favorites. I love all my old books, and each is a useful lense for looking at food in it's own way.

Professor Ken Albala's Food in History is one of my favorite Great Courses. Link to the course at the bottom of this post.

Our pigeon soup recipe isn't from any of those books, it's not even from a book at all. The original dish is from one of the most ancient food references on the planet: a 4000 year-old Sumerian cuneiform tablet I learned about from Professor and Author Ken Albala in his consumate addition to the Great Courses: The History of Food - Understanding Food Culture and History. If you have Audible, just download it and thank me later—it's great to listen to while you cook dinner. I think I'm on my 4th listen. Here's the recipe I wrote down from Professor Albala, direct from the tablet:

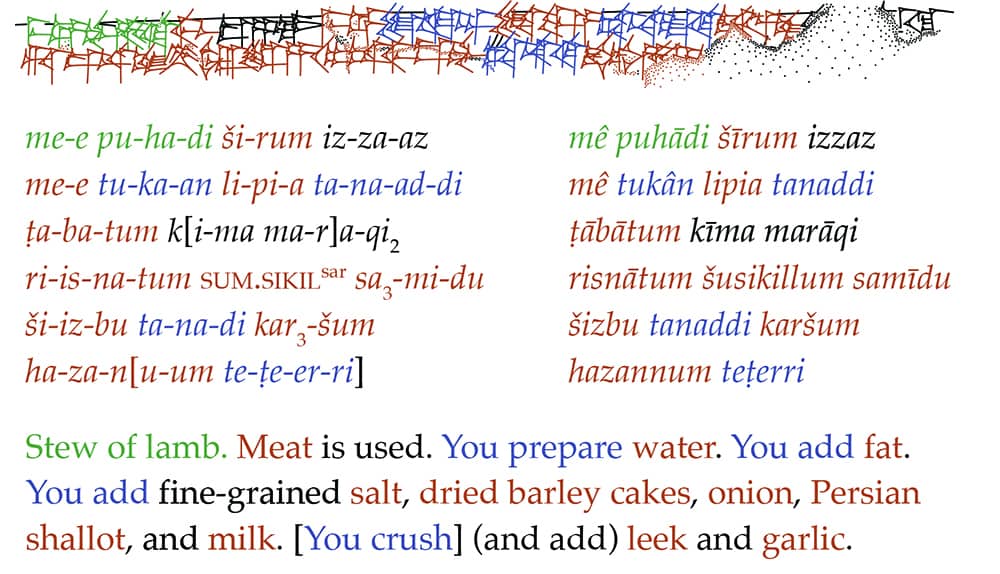

Credit: Yale Babylonian Collection

Amorsanu Pigeon Broth

“Split the pigeon in two, other meat is also used. Prepare water, add fat, salt to taste, breadcrumbs, onion, samidu (possibly semolina) leek, garlic. Before using, soak these herbs in milk and it is ready to serve”.

A similar translation from the tablets for lamb soup. Credit: Laphams Quarterly.

How I create recipes inspired by old books

So, I've never made a recipe verbatim from any old book, and I don't know if I would, as much for the fact that most don't contain quantities for the fact that I rarely follow any recipe verbatim sans pastry. I also don't think most people are going to make Sumerian pigeon soup, and that's ok.

Pigeons are rats of the sky to some. I think the patterns in most feathers are beautiful, no matter the bird.

Cooking with constraints

What's helpful here, what I'm trying to share with you, is an understanding of how the constraints you apply to your cooking and how you select your ingredients can transport your tongue to different times and places. A yellow onion grown in the United States is going to taste the same as one grown in China, more or less, it's the subtlety of the supporting ingredients and techniques alongside them that make dishes made with them that can steer a dish in the direction you want.

- Plucking takes time, but it's something I typically do.

- Plucking pigeons is easier than birds with down.

What I often do for conceptual dishes like this (hyper-local food is another example), is make a recipe that will taste good, applying constraints I think are appropriate for the time, region, or whatever I'm trying to showcase. Boiling a whole pigeon with some onions and then adding some unknown herbs soaked in milk doesn't really excite me. But, adding an ingredient or two cooks would have commonly used at the time, and tweaking the technique a bit so I know what the result will be is a good way to hedge the bet.

Historical fun aside, the basic recipe is a great primer for making simple stew from whole pigeons

Less is more, and unnecessary ingredients can muddy a meal. For example, the other day I was showing someone how I make Indian saag with shrimp, and they asked if they could season the shrimp with soy sauce. I quickly told them soy sauce was not an option, and we used salt, pepper and melted coconut oil instead. Little things matter. Here's some bullets on what I did here.

I brown the carcasses to deepen the flavor of the broth.

Notes

- Historical fun aside, the basic recipe is a great primer for making simple stew from whole pigeons

- Ken says he doesn't know what "samidu" is, some other references claim it's semolina, some an "unknown spice". I'm in the semolina camp (here's a helpful list of ingredients with cognates from nearby languages). What I know for sure, is that ancient cooks in the region also relied heavily on barley, so that's what I used here, toasted golden to bring out it's flavor.

- Beer was heavily used in cooking (and consumed regularly since fermentation made it safer than water) so I add some for a base note.

- Water can work, but you'll always get a deeper flavor from starting with broth.

- I brown the pigeons instead of just boiling them for a deeper flavor.

- Coriander and cumin were heavily used at the time, so I use both spices here, along with fresh cilantro leaves.

- Typically I'll finish light soups like this with a dash of lemon juice at the end, but since they weren't introduced to Egypt for another 2000 years after the tablets were carved, I use vinegar, which was definitely available.

I add a handful of fresh scallions at the end to keep some of their color and bright flavor.

The importance of onions

The Fertile Crescent, with it's flood plains and rich flat lands had the perfect growing environment for leeks and alliums, and they're omnipresent in many of the dishes I read about. Onions were worshipped as symbols of eternal life in Egypt, and they're the backbone of the soup besides pigeon or meat, so a big takeaway of the concept here is to use a big variety of onions—whatever you have.

Egyptian walking onions probably weren't traditional, but you could definitely use some here. I love these.

Fun aside: I don't see enough evidence to assume "Egyptian" walking onions were a cultivar originating from Mesopotamia, but Allium kurrat (Egyptian leek) is, and should date back at least 2500 years there.

Sumerian-Inspired Pigeon Soup with Barley

Ingredients

Pigeons

- 4 Whole pigeons plucked or skinned

- ½ teaspoon freshly ground cumin seed plus more to taste

- 1 teaspoon freshly ground coriander plus more to taste

- Kosher salt and fresh ground black pepper to taste

Alliums (just use as much variety as you can)

- 8 oz leek tender parts only, diced ½ inch

- 1 oz wild onion greens or chives (½ cup) divided

- 4 oz scallions, green garlic, or young onions (2 bunches) sliced into ¼ inch rounds, divided

- 1 tablespoon crushed dried ramp leaves optional, do not substitute garlic powder

- 2 Tablespoon minced garlic 3-4 large cloves

Broth

- ½ cup hulled barley, toasted for 15-20 minutes at 325 F or until golden or 1.5 cups cooked

- 5 cups chicken stock or water

- 2 tablespoons lard or cooking oil

- 1 cup light tasting beer a little bitterness is ok, but avoid strong IPAs etc

- ½ cup mild tasting beer don’t use a fancy one

- Extra virgin olive oil for serving (optional)

- Dash of vinegar preferably homemade, like apple cider or beer vinegar

- Fresh chopped cilantro, for finishing optional

Instructions

Pigeons

- Plucking the pigeons is optional, but allows you to brown them deeper than if they’re skinned.*

- Pluck the pigeons, but avoid the head, feet and wing tips—it’s a pain. If you want, peel the heads and add them to the broth.

- Use a poultry shears to remove the back bone, then extract the offal and discard everything but the liver and heart. Chop the liver and heart fine and reserve. Season the pigeons liberally with salt, cumin, coriander and reserve. Refrigerate the pigeons overnight.

Brown the pigeons

- In a gallon-sized pot, heat the lard and add the pigeons, cooking on medium heat, turning occasionally, until they start to give up their juice and a crust begins to form on the bottom of the pan. After 20 minutes deglaze with the beer.

Build the soup

- Add the water, garlic, ramps if using and leeks, along with half the onion greens and scallions, bring to a simmer and cook for 1.5-2 hours, or until the bones move freely from the joints. Skim impurities and fat here and there as it cooks. Cool the broth to room temperature, then remove the pigeons, pick the meat and coarsely chop. Discard the skin and bones.

- Meanwhile, cook the barley in 4x it's volume of water, then rinse with cold water to remove excess starch which will cloud the broth and reserve.

Serving

- Heat the broth and add the cilantro, scallions, reserved wild onion greens along with the pigeon meat and offal, heat through, double check the seasoning, adjust as needed until it tastes good, paying special attention to the flavor of coriander, which should be more forward than the cumin.

- Finish with a dash of vinegar to taste and a drizzle of nice olive oil, preferably Middle Eastern (Palestinian oils are nice)

Notes

*You can streamline this by adding the barley to the finished broth and allowing it to cook while you pick the meat from the pigeons, although the broth will be less clear.

Lois Luckovich

Sounds yummy. I made a mock chicken soup one day when there was nothing in the larder and my bf at the time shot pigeons

Anthony

Elegant photos! I agree with your philosophy that those older recipes were often a tad plain by modern standards, and modernising them is ok as long as it's done within the constraints of what would have been done at the time. A dish can better keep its integrity that way.

Great read.

Sylvie

I love to get into someone's head to understand what they do - and why! It's one reason that I don't really care for recipe books and why this is a lovely post for me. From the text from the tablet for lamb stew, it looks like "lipia" is the word for fat? Do you know if that is correct? Wouldn't it be so cool that the root for one of the words that means fat in English (and Latin-based language) i.e. "lipids" traces its origin back to Sumeria???? On a different note, why do you remove the skin from the pigeon and not mince it and add it to the soup? do you not like the taste? or texture? Just curious... I mince very finely chicken skin and add it back when I make (chicken) Brunswick stew... but I have not add pigeon since I was a kid, so I can't remember what it is like....

Alan Bergo

Sylvie. Great question and great observation. So, I would cautiously assume lipia is the root there, and that's a great observation I didn't even notice. I love language and the relation to food. Aside here, "Latin Alive" is a fun book not about food I use to help translate some things. As far as the pigeon skin you're challenging my paradigm here, and I need to thank you. I removed the skin because I was a bit sloppy and still had some feather follicles here and there on the birds, especially near the tricky places like the bottom of the legs. In hindsight, I should have added it, since I enjoy poultry skin after it's been well-cooked. Thanks for commenting.

Sylvie

I am the one to thank you, Alan! 🙂

Judy

Oh my! We have been trapping pigeons. They are beginning to overrun the barn. Now we know what to do with them.

Alan Bergo

I really enjoy them. I used to sell one pigeon breast with a 3oz piece of pork belly for 32$.

Autumn

I am going to try this with squirrel. Do you think that would work?

Alan Bergo

Yes. The marinating overnight (dry-brining) is a great technique for all kinds of small game too.

Aazmin

Please stop hurting animals. Eat veggies they are much more healthier what if you were an animal and someone cut you into pieces..we humans have no right to treat animals like that. Show mercy. Quit eating animals like squirrels.

Alan Bergo

I'm an omnivore, and it's very likely I eat far more plants by any measurement than you. I have a lot of plant-based friends who visit their website, and they are all welcome here, but I will not be taunted. You think a plant based diet is healthier? By what science? Name a culture around the world that is strictly plant based, wait, there are essentially none. But, on the other hand, there are indigenous societies in cold climates that have survived with minimal plant intake, and vast amounts of meat and fat, for thousands of years, if not longer.

If you don't eat meat, you'll need to take a host of supplements, and I have no interest in doing that. It's widely known that vegetarians generally start off strong, but gradually become weakened in many different aspects. Once you lose your sexual drive, start having dental problems and then opportunistic diseases from your weakened immune system you may want to change course.

As your body weakens, you can have babies with yellow eyes, jaundice, or in very bad cases of veganism, they can be born blind. Watch your body wither away being a vegetarian. Next time you hang out with your plant based friends, ask them how many of them have had vivid dreams of feasting on meat and gore that they're too afraid to share publicly-another little talked about phenomena in the plant based world that is basically the body's way of suggesting that we feed it what it needs.

Lissa Streeter

Oh my ! And here is my friend Ken Albala mentioned !

It’s so much more important (and a real gift) to describe your process and thinking on how you develop your work than « one tablespoon of this, one of that »...

Love your thinking about food Forager Chef...

Lissa

Alan Bergo

Thanks Lisa. Ken is just a treasure.