A journey into the first huitlacoche farm in the Midwest grown by Mushroom Mike LLC-now the largest huitlacoche producer in North America.

Driving through what could easily be mistaken for suburbs on the edge of town, I take a couple turns down some winding roads dotted with nice looking houses and big yards. I get to a stop sign, looking at the normal looking house on the corner and stop for a moment, confused.

I'm looking for a farm, but burbs is all I see. I grab my phone and call my friend who runs the farm, who informs me that I drove past the rendezvous point 2 driveways back.

I back up, and pull up alongside a small cornfield that seems like it could almost be the backyard of one of the other houses. Compared to most cornfields, it's small, but, as the saying goes, if you build it, they will come, and they (chefs) have.

I see my friend who runs the farm next to a pop-up white tent and drive up to meet him. Creeping past the rows of corn now, rubbernecking a few glances here and there at the green ears (a reflex any hunt-by-car mushroomer will understand), I start to get excited. I've been waiting over a year for today.

My friend is Mike Jozwik, the owner of Mushroom Mike LLC, a well-known and respected mushroom cultivator and wild food purveyor from South Eastern Wisconsin. Mike's looking his typical self, sporting an ear-to-ear grin.

To me, he's always been a kind of jovial, contagiously funny, friar tuck of the mushroom cultivating world, with the sort of nerdy passion for B-grade fantasy films that makes me think we'd probably have been friends in high school.

I'm not here to shoot the breeze about Hawk the Slayer or The Dark Crystal though, I've come to check out what is arguably his biggest passion projects: the first commercial huitlacoche farm in the Midwest. Today is the first harvest of the season, one of a few that will take place over the next few months.

I would wager that plenty of mushroomers in the Midwest, once they discover the hobby, have probably wondered, or at least drawn mental schematics hatching a plan to grow huitlacoche, a.k.a. corn smut, corn truffles, or corn mushrooms.

I mean heck, I tried (read as begged) my father, who farms a couple thousand acres of corn and soy to harvest huitlacoche, puree it in a blender, put it in a squirt gun and attempt to inoculate some of his crop. To say my father wasn't too excited about the concept of attempting to invoke something he tries to avoid like the plague is an understatement.

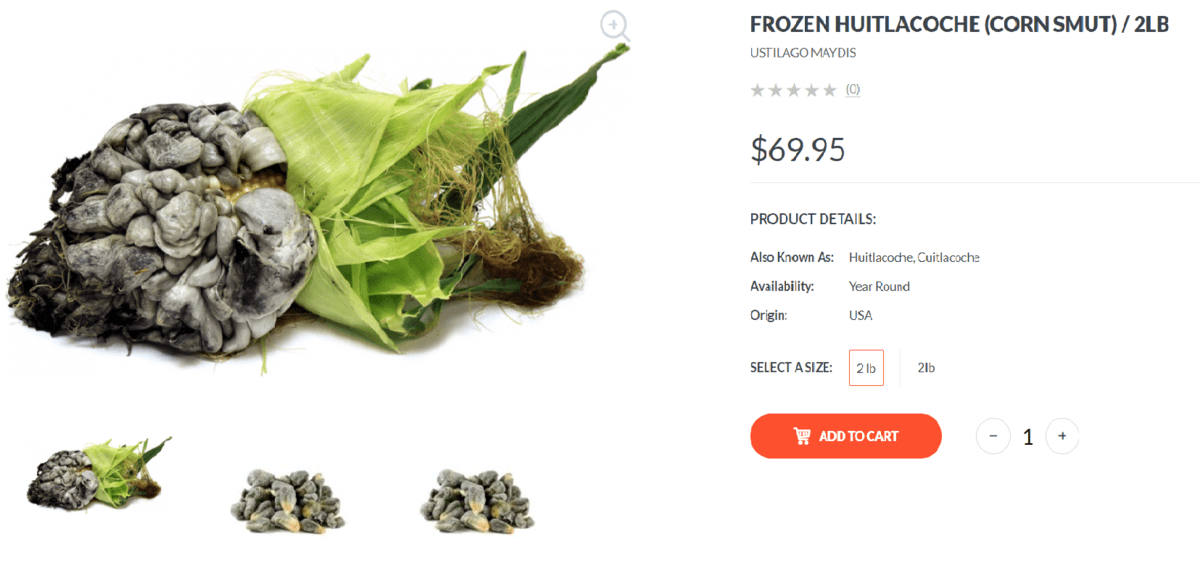

Mike though, is actually doing it, and at a high level. His Wisconsin huitlacoche is now spoken for a year in advance (he'll be taking advance orders if you're a chef next year, as well as selling flash-frozen, cut kernels) and, it's only his second year doing it on a commercial scale.

Yes, you read that right. He, and others like him are on the cutting edge of designing boundary pushing, paradigm shifting models of what the future of sustainable farm crops could look like.

After a quick mission debrief from Mike, I get the jist of the operation: walk the handful of corn rows bearing mushrooms, pick the most perfect ones and bring them back, unbruised and as perfect as possible, to be driven to chefs in Chicago first thing in the morning.

I came first to help out with the harvest, then to be a fly on the wall and just notice the goings on. The potential of an all-you-can-harvest huitlacoche free-for-all didn't hurt either.

Mike mentions something about eye protection and a facemask that I disregarded at first-a decision I'd later come to regret. The rows of corn are tight, requiring you to bend slightly to get through them at a brisk pace.

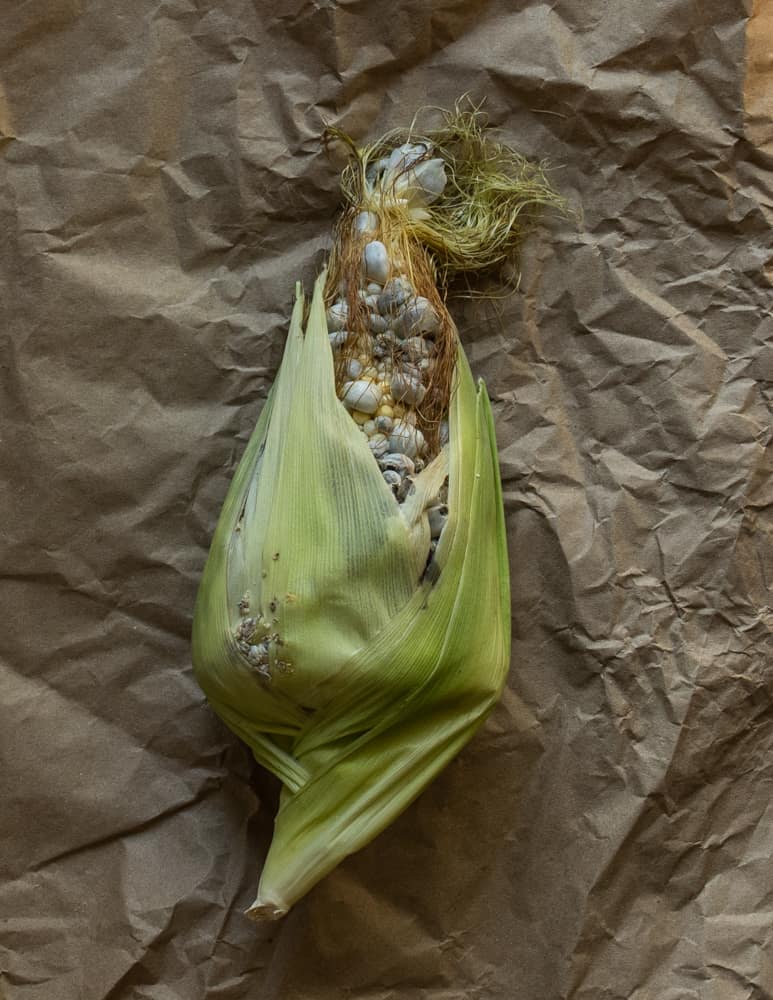

Almost immediately in the first row I walk through I see my first one though, what looks like an enormously plump ear of corn, the green husk seemingly ready to burst like the buttons on a shirt two-sizes two small.

I've picked huitlacoche before, here and there on small areas of damaged corn on my fathers farm and a few others. The fat, absolutely enormous ear I hold in my hands bears no resemblance to anything I've picked though.

Huitlacoche loves disturbance, some of the most common being floods, hail, and, the most dependable, at least from my experience: areas where deer nibble the cobs on the peripheries of the field.

When a deer munches a few bites or more from a cob though, it also reduces the potential yield of the mushrooms, since huitlacoche makes the individual kernels of corn swell into a plump, grey mushroom.

Mike's huitlacoche is the real deal, and by that I mean his ears resemble the kind of ears you see on Mexican You Tube channels. These aren't cobs that have a couple kernels that have grown into mushrooms, often the entire ear, from top to bottom, on the majority of the ears of huitlacoche I saw in his fields were colonized.

Huitlacoche Morphology

The exact method for inoculating the corn is a closely held trade secret, but, whatever Mike's doing, it's working. One of the things I truly found fascinating that Mike pointed out are the styles and morphology of how the mushroom forms on the corn-something I'd never considered.

At least on the day I was there, it seemed there were three noticeably unique patterns. After I left, Mike sent me an image of a fourth, or what he calls "variation wind chime" which I'd never seen or even heard of either.

Big Boy

The first is the big boy: a giant cob of dent corn filled with nearly every kernel turning to huitlacoche, each one larger and more impressive than any ear of huitlacoche I've ever picked in the wild.

Banana Flowers

The second is my favorite, what Mike calls the "banana flowers": ears that have swelled at the base, tapering at the top to form an alien ear of corn shaped like a cone.

Most of these are very heavy, so heavy that they bow on the plant, looking like they could snap right off the plant from the weight alone, and indeed, it's not unheard of, particularly after the peak of ripeness. Huitlacoche I've seen from South America often closely resembles this form.

Ice Cream Cones

These are ears that form huitlacoche concentrated at the top instead of up and down the ear. These, having a lower yield of mushroom per ear, Mike separates out for sale at a different price point.

Wind Chimes

Rain: a big problem

As I peel off the husks of a few ears to inspect them for quality, I start to see something alarming. Much of the huitlacoche is plump with water, and the moisture is making the mushrooms deteriorate quickly.

Unfortunately, there was a couple heavy rains days before Mike planned to harvest. If you're growing mushrooms indoors, a crazy storm is nothing to worry about. Huitlacoche, for many reasons, not the least of which being the space needed to grow corn, is grown outside, meaning Mike's crop, and all of the time, money and effort he's put into it, is at the mercy of Nature.

And Nature can be a cruel master. The previous rain wasn't a big problem, it was a HUGE problem. Any mushroom hunter worth their salt knows mushrooms will absorb water, (not necessarily a bad/avoidable) thing as they often need to be rinsed or swished to get clean.

Huitlacoche is not your average mushroom though, it's a delicate, tender thing, and, as I learned, incredibly fragile and subject to deterioration far quicker than any other mushroom I've handled in quantity.

Having row upon row of mushrooms all ready to harvest at the same time means that you harvest them en-masse as fast as possible once they're ripe. It also means that something like the weather can affect the entire crop at once, for better or worse, which is exactly what happened.

My excitement slowly turned to heartbreak as, one after one, each jumbo, mammoth ear of huitlacoche I found seemed just slightly past prime. At the end of a day and a half of harvesting I could tell the ones that were extra wet just by touching one.

I'd carefully cradle the base of an ear to see if I could feel water sloshing around the mushrooms at the bottom, soaking into the kernels making them soggy and wet, turning the mushroom romance of harvesting each ear into a sort of anti-climatic, depressing Ground-Hog's day.

This was the first harvest of the year that would go out to chefs, and if they weren't perfect, it could jeopardize the sale of the entire season's crop. You will not be walking into a restaurant selling macabre-looking ears like the one in the quick video below.

I started to worry as I struggled to find ears I would buy if I were the chef doing the purchasing, especially as the first two clients of the next day were Rick Bayless and Grant Achatz.

The fact those twos aren't just chefs, but culinary legends any purveyor of foods would endure bodily harm and or strange and unusual torture to even have the chance to pitch them on buying something, anything at all, weighed on me.

Comfortable as I am with harvesting quality mushrooms in quantity, I made sure to have Mike double check my harvests to ensure they were up to his standard. Just like his other products, Mike seemed to have two standards: perfect, or nearly so, and, compost. There wasn't much of an in between.

It may have been muggy and wet a couple days ago, but as we picked it just muggy and hot. Walking corn rows in the beating sun is not easy work, and, besides the heat, you have to watch out for the leaves of corn itself, as, when dried in the sun, the edges get sharp.

When I was a child, I cut my pointer finger down to the bone on an ear of flint corn, turning my friends birthday party into a scene from Children of the Corn.

The memory of a corn husk sliding across the bone of my finger like some paper cut from Hell still vivid in my mind, I eventually took Mike's advice and wrapped a bandana over my face, and grabbed glasses for my eyes.

By the end of the day, I could feel a hundred tiny cuts on my face from dodging the ears, my bandana a wet mop soaked with sweat occasionally waking me from the blissful automaton flow of harvesting with a sting as it hit one of the tiny cuts around my eyes. Next year, Mike plans on planting the rows farther apart.

The rain's damage was done though, and it was heartbreaking to walk through huitlacoche Candyland and have to toss cobs that had perfect bottom portions protected by husks, when the top portion exposed and breaking free from the husk was overly wet, looking too dark, or both.

Regardless, we still filled a truck full of boxes, a day and a half of harvesting netting about 700 ears from the patch for Mike to deliver.

I was nervous though. Would notoriously picky chefs understand the intricacies and vagaries of such a delicate mushroom?

Would they understand that if they want local huitlacoche they should probably just buy as much as possible regardless of aesthetic quality for the sole purpose of helping birth a new hyper local-niche crop? I hoped so.

Driving home I got a message from Mike, saying that the chefs at Topolobampo (Bayless's flagship restaurant) said the huitlacoche was perfect. Mike said he broke down in tears of joy in the delivery van after.

A few weeks later, I'm still having flashbacks and the occasional dream of walking seemingly endless rows of corn, here and there hitting the occasional gold mine: clusters of heavy fruiting we'd christen with names like "candy cane lane" or "all donkeys all the time". It was, literally, a mushroom hunter's Field of Dreams, and I can't wait for next year.

Sylvie

It i so heartening to read of growers like Mike. Thank you for sharing that.

Is it not possible to cut off the part of the cob that's gone bad if portion are still good? I know nothing about growing, harvesting, and cooking huitlacoche, so my question may make no sense... but given he price point, would "2nds" not make sense?

Alan Bergo

Thanks Sylvie, yeah he's a great guy.

Daniel Chong-Jimenez

As a child I ate many a huitlacoche, often in fresh corn tortilla and queso fresco quesadillas, but I never appreciated their origins until now. The story was impossible to put down, fun and satisfying.

Thank you Chef!

Alan Bergo

Thanks Daniel!

Diana Nickel

never heard of it, what does it taste like?

Kristin Balmet

Haven’t had the pleasure of corn cuts yet. Just harvested 10 gallons of cactus prickly pear fruits and am still tweezing prickers out of everything. I’ll have to work my way up to corn smut. There’s something so satisfying about the process of harvesting something difficult.

Lawrence Jozwik

Great article Alan, I hope you can make it again next year for the harvesting. I am sure Mike will have even more improvements on the harvesting techniques.

Katie Goin

What an awesome story … I teared up with Mike’s success. Corn smut is some tasty stuff 🙂

Alan Bergo

Thanks Katie. Me too.