Kentucky Coffee Beans, also known as mastadon peas (my name), have been on my mind, in my fridge, and in my belly all week. They are, without a doubt, the largest, tastiest and most interesting foraged legume (sans tepary beans, of course) I've eaten to date. This is a long, detailed post, with a lot of things to go over, so I'd grab a cup of coffee.

If you're not familiar, the Kentucky Coffee Tree (Gymnocladus dioicus) are tall, handsome, leguminous trees that makes large pods containing seeds, similar to honey locust and black locust trees. The seeds inside of the pods were historically food for giant herbivores that roamed the land who would snack on them, and disperse the seeds, helping the trees spread.

That the trees are still around makes them a sort of modern-day dinosaur food, hence the name mastadon peas.

Kentucky coffee trees aren't mentioned much in the foraging world, but Sam Thayer wrote about them in his latest field guide Incredible Wild Edibles. Wild Man Steve Brill also covered them.

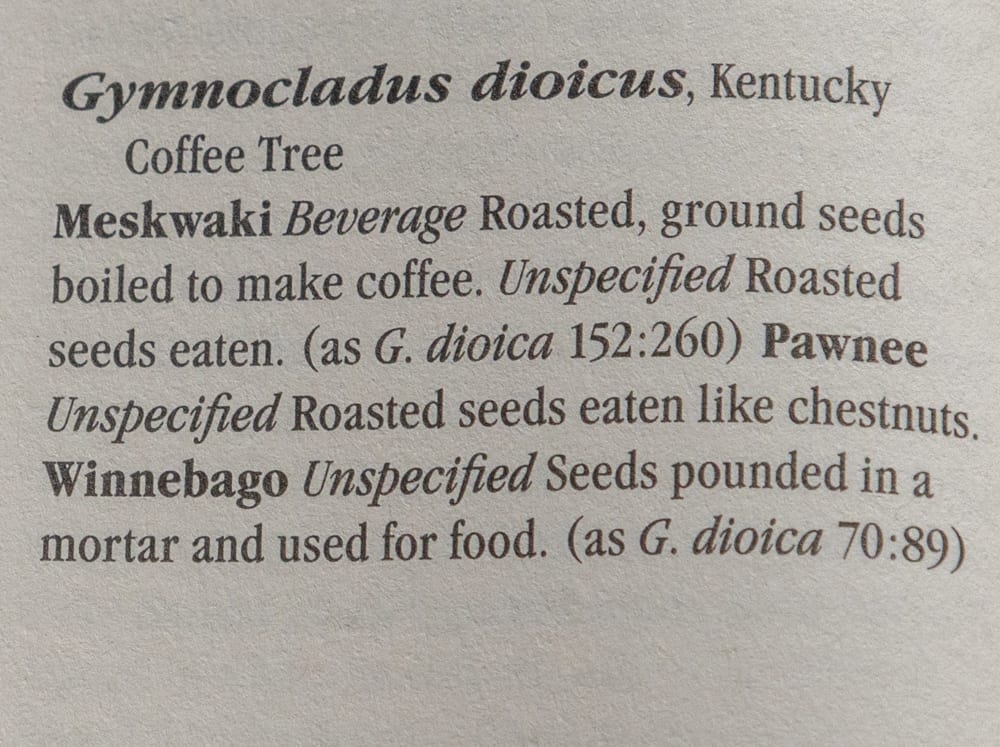

All of the literature and accounts of eating them I've read mention using only the mature beans as a coffee substitute, with Daniel Moerman also mentioning that the Pawnee (and undoubtedly other first peoples) consumed them as a food by cooking the shelled beans and cracking them as one would a nut. I've made the Kentucky coffee "coffee" and, sure, if I was on a desert island and starving, I might drink some out of boredom, but it isn't anything I find too interesting. I feel the same way about most teas.

The mature beans are a separate post so I'm not going to cover them here. All I'll say, is that If I harvest mature Kentucky Coffee Beans, I'll be roasting and shelling them to eat as a nut, and they're good, although very labor intensive to extract-more so than any nut I know. If black walnut shells are steel, then Kentucky Coffee Bean shells are adamantium.

Green/unripe Kentucky coffee beans though? They're a different world.

Story goes that my new friend JD from Brooklyn was reading my book Flora and, inspired by how I demonstrated cooking unripe sunflowers, decided to harvest some unripe Kentucky coffee pods. He sent me a message asking if I'd tried them, and we got to talking.

I hoped people would enjoy the book, but seeing people take some of the high-level ideas and apply them to things I've never thought of is a different thing entirely. I'd hoped people would apply some of the ideas in the book to other plants, but to see it happen, and then be able to go out and verify it in real time is something else entirely.

Needless to say, I cleared my schedule for a week to bring you everything you're seeing today, which is the product of multiple days of travel and scouting, and many hours of processing, cooking, and meticulous documenting, as well as about two hundred images. Special thanks to JD-without you this probably would've never happened.

Harvesting

You're looking for verdant green and or slightly yellow pods. The sweet spot will be in mid to Late August. Look for pods that are yellow to deep green, although if they have a very slight red flush to them they will probably still be tender enough to eat, provided the beans are still bright green after shucking.

Finding pods you can reach

Depending on where you are, this can be pretty easy, or nearly impossible. Typically, when I've hunted for Kentucky coffee trees, it has only been in the late fall and winter, after the trees have dropped their leaves. The pods stay on the trees and are easy to pick out, resembling a flock of birds or crows that can be seen at some distance.

Finding trees like that isn't rocket science, and harvesting the mature pods is pretty simple: find a tree in the early spring and pick the pods off the ground after you've had a good gust of wind or a spring storm, and go home.

Similar to how some trees make pine cones, the trees seem to produce the majority of their pods on the top two-thirds of the tree, and, as they can be very tall, the only way to get those would be a lift that could bring you to a height needed to work on something like a telephone pole-not the easiest or safest way to try and get some food.

Look for boulevard and urban plantings

As there aren't giant herbivores to spread the seeds anymore, the Kentucky coffee tree is not one that you'll probably see in the wild much. Rarely I will see one along a river, but, more than likely, you'll probably be going to a neighborhood park to get pods, not the woods.

Trees planted on a boulevard or in a park may be much younger than truly wild trees, and, at the right height, they will have pods that you can actually reach. With the right tree(s) it is possible to harvest large amounts of pods in a matter of minutes.

Cooking

Toxicity

Do a quick google, and you'll see the fruit of the tree labeled as poisonous, but, it's also a documented traditional food. While confusing, this sort of edible dichotomy is not unheard of.

So, the big question for me, and others that would like to try them, like other foods that must be detoxified to make them safe (potatoes, beans, flour poke sallet, milkweed, lupin beans and cassava) is: what are the toxins, and how, if at all can they be either removed or reduced to a safe concentration?

After looking at the toxins themselves, another, very important thing I take into consideration is dosage. For example, cinnamon and nutmeg are heavily used spices, yet both have toxic thresholds that can be breached if taken beyond the quantity of normal use.

The book Toxic Plants of North America says this:

(Gymnocladus dioicus has) "A water soluble, heat labile toxin or group of toxins are present in the leaves and seeds. A group of complex glycosides called gymnocladosapponins may be responsible for the toxicity associated with consumption of the uncooked seeds or leaves. The cooked seeds were at one time tried as a coffee substitute.

Poisoning of livestock has been associated with animals drinking water into which the Gymnocadus seeds had fallen. The toxins appear to have gastrointestinal irritation and narcotic effects".

What are the "toxins"?

The sentence I pull out from the above is this: “A group of complex glycosides called gymnocladosapponins may be responsible for the toxicity associated with consumption of the uncooked seeds or leaves.”

So, the problematic compounds are saponins, the prefix "gymnoclado", making it essentially “Kentucky Coffee Tree Compound”. So, basically, we don’t know what it is beyond that it’s a saponin, or group of related compounds, cousins of which are also found in related plants like chickpeas and (unrelated) quinoa.

For clarity here, I'm not trying to downplay that the seeds could make you sick if eaten raw, I'm just trying to zero in on how, and why, the beans are known as being both toxic, and edible.

So, how are sapponins removed from food? The words "water-soluble" and "heat labile" are nice to see here, meaning, that the "toxins" should be removed (at least to a safe concentration) by boiling in water, and also denatured by heat.

In short, just boil'em like any other bean, discarding the water being a differentiating factor. It goes without saying you wont be using coffee bean cooking water to make aquafaba.

Parallels in other plants

Consider two other plants that are toxic and also edible. Edible milkweeds (A syriaca and speciosa) are toxic raw, containing cardiac glycosides that are removed by boiling.

Cassava, Chokecherry, Bird Cherry, and Prunus mahlab, as well as all species of apples and basically everything in the genus Prunus are well-documented traditional foods, but their seeds also contain cyanogenic (cyanide) glycosides, which are also removed by various means of processing, and, in my mind, are probably more dangerous than Kentucky coffee beans (cyanide poisoning from cassava is well-known).

Livestock poisoning vs human consumption

All of the poisonings from Kentucky Coffee Tree I can find are related to livestock, and it seems fairly easy to parse. Here's what might happen: A pod falls into a water trough. The pods sit in the water, the heat of the sun warming the water into a sort of Kentucky coffee pod sun-tea, then, the animals drink the water, and, from there, suffer gastro-intestinal and apparently “narcotic” effects.

At first glance, this sounds kinda scary, but, an important distinction to make here I think is that livestock are eating either raw, uncooked seeds, or, more specifically, the infused water the seeds have transferred their problematic, water-soluble compounds into. What happens when animals eat cooked seeds understandably has not been covered, as livestock don't boil their food.

Dosage

I've seen similar parallels here in cautions and dire warnings slapped onto mundane edibles like chickweed. For example, If a cow eats five pounds of chickweed and gets sick, it could very well get labeled “poisonous” by the powers that be (read as livestock feed companies, etc).

This may be helpful for livestock and the people who tend them, but, when’s the last time a human ate five pounds of chickweed? I’ll tell you: It doesn’t happen, and drawing a parallel to chickweed being poisonous to humans as a result of such a quantity being consumed by livestock, when it is a documented traditional food, is a big, fat, logical fallacy and gastro-fear mongering.

As my talks with Sam Thayer about his process of eating new-to-you wild plants has taught me, you can get sick eating just about anything, if you eat enough of it.

What was on my mind, was this: If lupin beans (which I go over in my book) which need lengthy leaching often surpassing a week's time to remove water-soluble toxins, are a traditional eaten legume cultivated in both the Mediterranean and South America, then I would be very surprised if Kentucky coffee beans can't be made edible.

Cooking

Over the past week I've eaten over 2 pounds of shelled, green Kentucky coffee beans myself cooked exactly the same way each time, and, after eating them, not once have I even experienced any discomfort. Heck, I even seem to digest them better than other legumes-not even a single, tiny fart.

Detoxification

Here’s the method I’ve used: shell the beans and discard the pods. Cover the pods in water, using roughly 3 cups of water for every 2 oz of fresh beans. Bring the pot to a boil and cook for twenty minutes, discard the water, cover with more water, and boil for another 20-30 minutes, or until the outer shells are tender.

From there, you can use them for whatever preparation you have in mind where fava beans or large legumes would be welcome. It could be that the second boiling here is unnecessary, but, until I’ve eaten them cooked like in quantity to test my theory, I’ll leave my cooking recommendations the same as what I’ve done here, for continuity.

To shell or not to shell?

Just like fava beans, Kentucky Coffee Beans have two shells: the outer large pod, and the inner shell that will get harder as the beans mature. If you’ve cooked fava beans with some regularity, you might know that if the beans are very fresh and young, the green skin covering the individual beans doesn’t need to be removed. If the beans are older, the shells should be removed as they will be tough.

Green Kentucky coffee beans seem to function similarly, and it may take some experimentation to figure out if you’ll prefer your beans shucked twice, or simply once.

When cooked at a rolling boil for 15 minutes or so, the beans will retain a bright green color of a fresh fava bean, but the outer shell will be too chewy for most, so you will probably want to shell them.

Extended Cooking

If you don’t feel like shucking the beans, or can’t be bothered, it’s ok. Most of the beans I've eaten have been long-cooked (30-40 minutes or more) after which I eat them, inner shell and all. Kentucky coffee beans are incredibly sturdy, and seem to cook more like a dried legume than fresh.

Flavor

The flavor of the ripe, brown beans, after roasting and shelling, is mild, barely sweet and slightly nutty, a bit like a peanut or a cashew. The young, green beans, are very different.

After boiling, fresh, green Kentucky coffee beans taste reminiscent of milkweed and endamame to me, with a noticeable leguminous sweetness that will remind you of fava beans.

They’re excellent, delicious all by themselves with a pinch of salt and good oil, and on par with any other legume I’ve eaten, wild or cultivated, which should tell you a lot. Here's a few ideas for sampling them.

Ideas for Enjoying

- Eat like edamame. Score the inner shells before boiling, cook until the beans are tender, then shuck them at the table warm and eat with good salt. I recommend you try this first before you do anything else.

- Cook the beans and allow them to sit in a light brine, as for lupin beans, then enjoy as a snack as you would with antipasti, or tapas.

- Try an Italian classic: fresh favas are eaten, shell and all, with chunks of pecorino cheese and a glass of white wine.

- After cooking per my intro method below, the beans can be shelled and used anywhere you would use fava beans.

- Marinate the beans in aromatic oil after cooking (method in the recipe notes below).

- Brine the beans as described and marinate in aromatic oil, mixing them with your favorite olives.

How to Cook Green Kentucky Coffee Beans

Equipment

- 2 quart sauce pot or larger

Ingredients

- 2 oz Green Kentucky coffee beans, removed from the pod

- Water as needed, about 2 quarts

Instructions

- Cover the beans with water to cover by 5 inches, bring the pot to a boil, turn the heat to a simmer, cover, and cook for 20 minutes.

- Pour off the water, replace it with another batch of the same amount of hot water (I like to use a steam kettle to decrease the time it takes for it to come back to a boil), cover the pot, bring to a boil, turn down to a simmer, and cook for another 20 minutes, or until the beans are tender enough that the skins can be chewed and no longer taste rubbery.

- The skins will remain a bit al dente, but not in an unpleasant way. Rinse the cooked beans in cold water to remove any clinging mucilage (unshelled beans will also transfer mucilage to liquid if they sit in it.

- From here the beans can be eaten as is, but I prefer to soak them in a light brine (see note) marinate in herb-infused oil, or well-seasoned tomato sauce, etc. They make an excellent antipasti, but can also be shelled and used as you would other legumes or simply with salt like edamame-my girlfriend's favorite.

Notes

KCB Edamame

With a paring knife, cut around the seam of the pods, entering about ¼ inch into the pod with the knife, imagining how the blade will barely knick each bean as it slides through the pod. Wear gloves. You can also score the beans with a paring knife after shucking. Slicing open the beans before cooking helps you to peel them as you would endamame. Boil the beans until tender in a change of water (30 minutes of boiling total) then cool until warm, and eat, shucking the beans indivually, sprinkling with good flaky salt like Maldon or Faulk.Brined Kentucky Coffee Beans

For a pint jar (small mouth) take 220 grams of cooked beans, still in their tender, inner shell (Generous 1.5 cups) put into a jar, then cover with 6 grams of kosher salt (1 teaspoon to make ~3% brine) 220 grams (generous cup) water, screw on the lid, shake, and refrigerate. The beans will keep for a couple weeks. Overtime, the beans will transfer mucilage to the liquid, to refresh them, discard the liquid, rinse the beans and agitate them for a few minutes in warm water, then rinse, put back in the jar, and cover with another batch of brine. I like to rinse them before I serve them, too.Kentucky Coffee Beans in Herb Oil

For each 2 cups of cooked beans, take ¼ cup extra virgin olive oil and ¼ cup flavorless cooking oil, combine and heat with a grated or smashed clove of garlic, a couple sprigs of thyme, or a small sprig of rosemary. Heat the oil in a pan until sizzling, then turn the heat off and cool. Add a pinch of chili flakes while it's still hot. When the oil is cool, combine with the beans, seasoning with a good pinch of salt. Refrigerate the beans in a shallow container or other dish. To serve, toss the beans to coat with the oil a few times, allowing them to come to room temperature before serving. They'll last for a week in the fridge.Resources

Sam Thayer: Incredible Wild Edibles

Steve Brill: Identifying and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants

Shawn

I would suggest researching the lectins this bean might have. They are common in legumes and can be highly toxic (ricin for example). Saponins are generally not thought to be toxic. It seems like your cooking process would denature the lectins, I wonder also about sprouting, and the need to remove that hull.

Alan Bergo

Lots of things have lectins, like quinoa and all the Chenopods. The hull can be removed through nixtamalization if they’re harvested mature.

Megan

Excellent article, as always!! Thank you for the information! In my first boil right now for a batch of raw beans. Denver is chock-full of KCTs and they're plentiful on most of the trees right now. I am hoping to play around with this first batch and then would love to experiment to preserve batches like those delicious little marinated olives. Alan, do you think you could do a brined water-bath canned batch, or would the extra cook time get them way too tough in the end?

Alan Bergo

Hi Megan, you would need to ferment the beans shelled individually to prevent them from getting really mucilaginous.

Sama

Hi Alan,

Thanks so much for another great article! I was wondering if you had any recommendations as far as preserving them. I was going to try a simple pickling solution, as that seems like it would preserve the texture the best, but I’m curious if you have any recommendations. Thanks!

Alan Bergo

HI Sama. I've successfully frozen them raw and then boiled them from the freezer. You could pickle them, but you'll want to remove the beans from the inner green shell individually, otherwise the mucilage will get really thick.

Sama Cunningham

Thanks Alan! I’ll give that a shot.

Ian Campbell

Alan,

Fascinating post and well done on the research! I first noticed this in Sam Thayer’s field guide, which was interesting because he didn’t mention the immature beans when he covered the tree extensively in an earlier book. He mentions eating the immature beans when they are pinkish/yellow in mid-late Summer while you say to go for the green ones in mid-late August. I found some that had blown down from a storm in Wichita, Kansas on June 23rd and they were green to greenish-yellow. When I opened the pods, the beans looked very much in the stage that I had seen on your site and when I boiled them, they had a perfect lima-bean like look and consistency. I boiled them for 20 minutes, drained the water, rinsed, and boiled again for 20 minutes, rinsing one more time. The first night I ate 5 or so, salted and in oil, with no problems. Delicious. The next morning I ate 5 more, no problems.

That second night, I ate 8 of them, boiled and rinsed in the same way, and convinced myself that I felt slight burning in the back of my throat. I then convinced myself that I had eaten them way too early in the season and because of that, there must be toxins that were plaguing my body. Outside of that (imagined or not) burning feeling and some definitely imagined psychosomatic symptoms, I had no issues. I ended up composting the rest of the beans anyway and decided I would wait until late July or August (when, judging by iNaturalist pictures I took last August, they would still be green/greenish yellow). Sure enough, they look about the same inside and out as we approach the beginning of August. I boiled some last night in exactly the same way, paired with a sort of shepherd’s pie that was a great showcase for your walnut catsup, and found them delicious except for the fact that even after the long boiling, the outside was very chewy this time.

Do you have any thoughts on my experiences here? Is it possible that they could "ripen" or get to the ideal unripe "fava" stage that much earlier in Kansas, or is it likely that I ate them too early the first time? Could this be an early-ripening variety, or could they possibly have a longer season than assumed? Finally, do you have any thoughts on the difference between yours and Sam’s suggestions of the color/timing in which to get the unripe pods?

Thanks for pondering these things with me and for being so responsive to feedback!

Alan Bergo

Hi Ian. As you might know Sam is a friend of mine. If we had known about methods of eating the unripe beans at the time he wrote Incredible Wild Edibles he would've covered them in that book. The outer skin of the beans is always slightly chewy, for the best experience you'll want to remove the beans individually from them, which is kinda tedious, kinda like favas. If you're in Kansas your beans are probably ready earlier than mine, as I'm in Minnesota. I'm here if you have more questions and I'll try to speak to as much as I can.

Bob

You mentioned Honey Locust in your post as a similar type of seed. I think that that may be a more fruitful area of inquiry. There's lots of people online who I've seen suggesting the pods as a good feed for livestock. Apparently the animals enjoy them quite a bit, even the fully mature ones, so I would guess that toxicity is not as much of an issue. Might be worth looking into.

Brian

Have you ever managed to find a good use-case for the ripe beans? I just harvested some a little while ago and they really just taste like (slightly fruitier(?)) coffee to me which makes me think I might as well just get instant coffee for any recipes that require a coffee flavor seeing as it’s so unworthwhile to crack these stupidly hard beans

Alan Bergo

Hey Brian, I haven't. The nuts are so hard to crack that it's a deterrent to cooking with them, at least for me personally.

Brian

I’ve found that using a mortar and pestle after roasting takes about as much time as a hammer to black walnuts - not a great speed, but not terrible

Alan Bergo

Yes you’re right, I’ve done it too. With enough help you could definitely get enough weight to cook with. I always thought it would make a fun nut butter.

Bob

Have you tried soaking them? Most of the guides for planting from seed them suggest scarifying with boiling water them and then leaving them to soak for 24-48hrs in order to break the seed coat. I'm not sure what this would do for the palatability, but it would probably be the most efficient way to get them in a suitable state for mashing/cooking.

Eg

Has anyone ever eaten the green flesh…similar consistency to avacado

Alan Bergo

Don’t do that. You’ll poison yourself.

Orn

Isn't that the part that megafauna would eat them for? Weird that that'd be the toxic part.

Alfie

About 20 years ago a friend gave me some trees to plant in my yard. [I live in Oregon] He said one of them was a KCT, but I paid little attention since I do not drink coffee. I looked it up once just to find out that the berries were toxic. I just read your posts, and now I am interested. My tree is well established. I am anxious to try some of your suggestions for preparation. I drink MANY herbal teas for nutritional and medicinal benefits. Other than taste, what would be the benefits of eating these seeds?

Alan Bergo

My words should be considered anecdotal here as I'm not a nutritionist. There's a number of legumes that provide nutrients but also need to be leeched or processed to remove toxins. Lupin beans are a good example. The nutritional benefits should be comparable to other green legumes, like green chickpeas, likely with some loss of water-soluble nutrients from the extended cooking process.

Sunday Harrison

Hi! What a fantastic post. I especially like that you took a week to write it and meticulously described the process you implemented. We've been growing the tree from seed, using the over-wintered seed pods, extracting the seed, sanding it and soaking it to get it to germinate. We probably get about 70-80%, higher than many tree species. Anyway, it never occurred to me to try eating the green seed. Your post made it happen! We followed your instructions and then made hummus, with cooked KCT beans, garlic, olive oil, lemon and tahini in a blender. It's pretty good!

Alan Bergo

Glad it was helpful. I prefer to eat them in their natural form as opposed to pureeing them into something. You can make hummus out of anything, but fresh cooked KK beans are a once-a-year treat.

Daniel

I just love your posts!

I’d seen this in Sam Theater’s book, but I’m usually a hard pass on coffee-alternatives. A lot of work, and rarely as good as decaf coffee, which I also don’t bother with. Coffee is a very high bar to compare things to!

This, on the other hand, is very interesting, and I happened upon a perfect, low-to-the-ground specimen. Very excited to explore!

Ross

I have a couple young trees in my rural area I am watching for the pods to ripen later this summer to give these a try. I have made coffee from the ripe beans myself and agree it’s not that great and a lot of work. It does give a mix with coffee beans a nice taste though. Thank you for this detailed recipe and article.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Ross. Let me know how you like them.

Greg Martin

Does anyone have suggestions on good places to get high yielding trees or seeds? Would be wonderful to help spread this amazing tree. Thank you so much Alan.

yitzkhak Kaufmam

Great Post

Keith

I've always heard the seeds were poisonous but that a coffee substitute could be made from the roasted beans. I tried roasting the beans last year. As you have stated, the seeds were still hard as rocks AFTER roasting. The smell was also unappealing, so I passed on trying the coffee. Good to know the green beans are more useful. Alan, have you ever tried yellow nutsedge, cyperus esculentus? It has naturalized in wet areas throughout the US. It has a small tuber that can be dried, roasted, powdered, and turned into a drink. I'm hoping to dig some of the tubers this fall.

Terry

While waiting to hear about Alan's explorations with Nutsedge, I thought I would chime in. AKA as Chufa or Tigernut, it is a treat just to eat the tubers which are sweet, crunchy and reminiscent of almond. They take awhile to sprout, but are easy to grow, either in wet places or regular garden soil, even in pots. Grown around the world, a common way to eat them is as a drink, like you say, (horchata in Spain) and it is also increasingly easy to find a flour made from them. I have used it as a flour in various combinations with almond flour, cassava flour and teff flour for various baking and breading projects.

Alan Bergo

Terry, no experience with nutsedge for me sans cooking with Tigernut flour from the coop 🙂

Tim McCormack

Put the brown KCT seeds under a metal loaf pan on a baking sheet (to contain the explosions) and roast at 325°F for about 90 minutes. Once they cool you'll need to crack them by applying force (a vice or a brick) to the seeds longways, at the point of the seed. They should fall in half. The contents can be finely ground and used in a Turkish-style coffee (grounds-in).

They definitely don't taste exactly like coffee, but they make a pleasant coffee-like beverage, especially if mixed with carob powder or another sweetener. (It's also interesting how much they smell like coffee *flavoring* rather than coffee.)

Krista Willmorth

I really appreciate the documenting of your method here for trying new foods (and it reminds me I need to get Sam Thayer’s latest book). I was literally just walking through a park yesterday looking at the green pods and wondering, since I’d heard the dried beans could be used for a beverage, if the green pods could be safely consumed. So I will definitely be trying this this week!

Point of clarification: I assume when you mention under notes for making the brine that you add the salt, beans, and *water* to make the brine, right? Seems obvious, but I wanted to confirm.

Thank you!

Krista

Alan Bergo

Thanks Krista, and yes, I forgot to add the water there, that and adding salt are probably my two biggest typos, lol.

Milton Goldman

It's a surprise, a relief, and a joy to see this posted by you, sir. I've followed your blog for a couple years now and am a huge fan of yours, especially when you document your cooking of animal parts, visceral pictures and all. Huge fan. Two days ago, I stumbled upon a Kentucky Coffee Tree in Manhattan. I had just gotten off the phone with a family member, and we discussed some rather unpleasant things, putting me in a bad mood and in a dark place. After the call, I stepped out of my car and saw a large mature KCT in front of me, with some pods on the floor. I decided to open one up and consume a raw pea (double "shucked," as you put it). Delicious splendor! Edamame taste, as you describe, with a nutty, crunchy texture with some vanilla and almond mouthfeel. I only ate one raw pea because I had no idea what it was. After posting on reddit about it, here: https://www.reddit.com/r/foraging/comments/pcs28a/can_someone_please_advise_what_these_are_i_ate/ and learning that they were toxic, I had a panic attack, followed by receiving a torrent of comments about how dumb I was for eating something I didn't know (100% deservedly), others saying they admired my bravery, others hoping I was OK. I'm laughing about it now. (I feel fine.) I joked with my wife about how I'd go back and harvest more and cook them this time, but she said I'd had enough fun for now. BUT, after seeing your meticulous post, I think I will actually go back to the trees (down the street from me) and follow your recipe. My only concern is bioaccumulation of toxins, being in a large city and exposed to auto emissions. I guess I'll have to think about it. Thanks for your post, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Milton, a lot of work went into this. As far as bioaccumulation, here's my thoughts. Bioaccumulation of toxins and the environment food comes from is definitely good to take into account, particularly with things that will not be boiled in two changes of water for an hour, as with the green coffee beans here. Mushrooms especially are prone to absorbing toxins. With the beans though, I would eat them from plenty of spots without worry, the extended, lengthy boiling, as well as the change of water I include which in itself is probably overkill, make me very comfortable eating these. I would wager that walking around a busy town (NY) and inhaling exhaust fumes is more dangerous than eating a few handfuls of beans each year that have been boiled to the next dimension personally. As far as Reddit, yes, being roasted over the coals there is something I may have experience with! Good for you for being a good sport about it.

Barbara

An interesting thing I learned about mushrooms and toxins.

I ate a batch of morel mushrooms (which I love) and got very itchy! I thought I had developed an allergy to them.

But then a local mushroom forager told me about the dangers of picking morels growing near poison ivy.

I am very sensitive to poison ivy!

When I ate carefully picked morels, I did just fine!

So beware!

Alan Bergo

Haven't heard that one yet. Thanks for sharing Barbara.

Kristin

Lovely photos I’m so inspired

Alan Bergo

Thanks Kristin

Ellen

What a great post, Alan! Thank you.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Ellen.

Jean Hatter

I have two Kentucky Coffee Trees in my yard that I grew in Horticulture class in high school. These are approximately 45 years old.

I am wondering the roasting time for the brown beans before eating them.

Alan Bergo

It's weird. People just tell you to roast them until they explode and make "coffee" out of that. Not for me.