She is the Tuscan queen of weeds. Over the past year I’ve stumbled on a few recipes using wild plants that really inspired me. At the top of the list is la Minestrella, a sort of ultimate foraged greens stew found in Garfagnana (Tuscany) I stumbled on while doing armchair research on the Italian names of wild edibles.

Entering specific names of edible plants into Google can be as sort of invocation that transports you to different edible time and place with the click of a mouse, and la Minestrella is the poster child for that kind of journey.

Somewhere (probably an online excerpt of Mediterranean Food Plants and Nutraceuticals) I saw something in Italian like this:

“Regional specialty....typically including anywhere from 30-50 individual species of plants, Gallorini beans, served with the mignecci”

I was hooked, and I knew I wouldn't be satisfied until I’d cracked the code and tasted a version myself, or at least the closest thing I could come up with.

I had lots of questions, mostly involving what specific plants were traditionally used and if I could find them, but first, I’d need to find some info on the soup, a mention, a recipe, anything, which is easier said than done. There’s some documentation online, and a recipe or two, but they’re mostly vague outlines with fuzzy pictures. The translations, even with my decent knowledge of Italian culinary terms, didn’t give me much, especially when it came to decoding the mignecci, a sort of unleavened cornbread that’s served alongside the dish.

I made a note and created a file with images to refresh my memory, a process I find helpful when squirreling away little things I find here and there until I'm ready to work on them. Some accounts say that only elderly matriarchs now hold the native knowledge needed to pick the variety of wild plants needed for the dish, a parallel most of us can agree is a common thread woven through cultures, women often being the culinary gatekeepers to techniques and traditions, those unspoken secrets and intuitive flicks of the wrist like a sort of code hidden in recipe cards only Grandma's eyes can see.

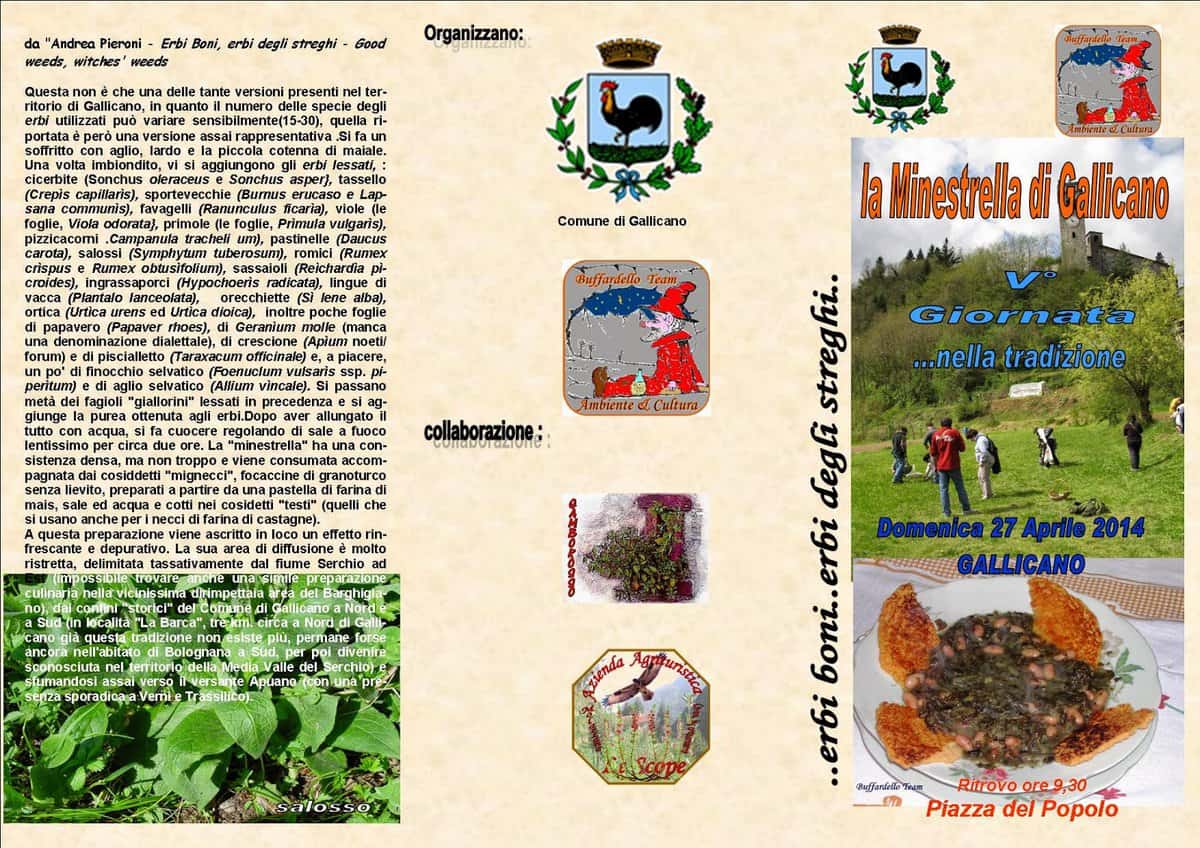

The most helpful thing I found was a set of pictures of a brochure outlining the Minestrella festival (!), that, besides making want to plan my own festival around a dish of plants, gave me the key to unlock how the mignecci are made. I'd been confused about the cakes and the cooking process, as the translations kept referring to cooking the cakes in "books" or "texts". When I saw the two flat irons in the upper right corner of the first page, I put two and two together. The "book" was referring to the two pieces of iron, that when heated in a fire, could be pressed together to make the cakes with the circular pattern I kept seeing in image search results. Booyah. Brochure source

Use the biggest variety of wild plants possible

From there I was off to the races. As far as the plants, calling for as many as 30, 40, or 50 plants says one thing to me: this is a dish born from poverty, from necessity, like the edible season incarnate. It’s the poster child of subsistence food, better known in Italian as la cucina povera.

In my mind, the exact combination of greens, herbs (and flowers, especially violets) probably isn't important as using the largest variety possible to make a dish where the sum is greater than the parts. That being said, there's a few plants specifically that I kept running into. A few are listed in the previous picture of greens, some are taken from other sources after I saw them repeatedly.

- Dandelions (Tarraxacum)

- Primola (primrose)

- Rucola (arugula)

- Alliaria (garlic mustard)

- Wild lettuce (Lactuca spp)

- Violet flowers (interesting not violet greens, but they may be added)

- Docks (Rumex, various species)

- Wild chicory (Cicoria)

- Campion (I assume S. vulgaris and/or Inflata)

- Geranium leaves (unknown species)

- Purslane

Variety is definitely the spice of life here. I've made the dish a number of different times now, and I found if I get lazy, and use a larger quantity of one plant, that flavor can become dominant. The key is to use the biggest variety you can find, and don't be scared about including some strong and/or bitter flavors.

Purging the greens

Another part of the dish I ran into a few times is the method of how the greens are cooked. The Minestrella usually contains bitter greens, some reputedly very bitter--probably not what you typically think of for soup. The method (what I call the purge) is to blanch the greens (I assume in unsalted water) then let them soak to soften the flavor of strong tasting plants. Of course some flavors are muted doing that too, and in classic French cuisine it might be heretical, but it's a creative, resourceful way to calm flavors, and one I also came across researching Italian recipes for strong tasting plants like angelica.

Mignecci

Onto the cakes. The mignecci here are really simple, nothing more than some cornmeal, water, flour, salt and a pinch of herbs. The magic is in the cooking. I didn't have the flat iron tools that are traditionally used to cook them, but I did have something similar in my family's krumkake iron, which has the added bonus of making the cakes look like engraved coins or doubloons-- fitting for a recipe that's a kind of culinary treasure chest, right?! But, if you've lost your krumkake iron, you can make the cakes by inverting a cast iron skillet on top of a gas burner, pressing another lightly oiled, very hot skillet on top of the batter to cook it. Or, with an electric stove, just make little hand patties, close your eyes, and pretend.

Now, when someone asks you what recipe uses the most wild plants out of anything you’ve heard of, you can bring up la Minestrella. I hope it can inspire you to think about how a simple mix of greens, in the right context, can be like eating a bowl of history.

La Minestrella, The Italian Stew of Many Greens

Equipment

- 1 gallon pot for blanching

- 1 3 quart soup pot for the soup

Ingredients

- 12 oz wild greens largest variety possible

- 1 medium yellow onion 4oz

- 1 small carrot 4 oz

- 1 small rib of celery 2oz

- 2 large cloves of garlic ½oz, chopped

- 2 cups 10 oz cooked cannelinni beans or roughly ¾ cup (3oz) dried beans

- 1 cup bean cooking liquid or stock

- Kosher salt to taste

- 4 cups homemade pork chicken, or vegetable stock and/or a combination using the bean cooking liquid

- ¼ cup olive oil plus plenty for serving

- Fresh cracked black pepper for serving

Instructions

- Bring a large pot of salted water to a boil and blanch the greens at a rapid boil for 1 minute, then refresh in cold water and allow the greens to sit in it for at least an hour or so to help calm the flavors, especially if using strong tasting greens. If you like mild greens, you may not need to soak them.

- Remove the greens, squeeze dry and chop medium-fine and reserve.

- Puree the carrot, garlic, onion and celery in a food processor or blender and reserve.

- Heat the oil in a soup pot and cook the vegetable puree for 10 minutes or until starting to brown around the edges, stir it here and there so it cooks evenly, you want to tame the garlic here. Add the stock, bean cooking liquid, or enough liquid to make a puree, and ½ cup of the beans, heat, and puree with a handblender (food mills are often used).

- Add the greens and the rest of the beans, season with a good pinch of salt and cook for 30-45 minutes, or until the greens are very tender. Double check the seasoning, adjust as needed for salt and pepper, also consider adding some liquid if it looks dry, and, preferably, chill the soup overnight to let the flavors meld.

- To serve the soup, ladle 1 cup of soup into a bowl, garnish with plenty of olive oil, fresh cracked pepper, and one of the mignecci, cut in half, to scoop up the greens with.

Notes

Nutrition

Mignecci

Equipment

- 2 cast iron skillets (or a krumkake iron!)

Ingredients

- 210 grams 1.5 cups corn flour (I use high-lysine cornmeal from Whole Grain Milling)

- 210 grams 1.5 cups all purpose or whole wheat flour

- 310 grams Roughly 1.3 cups cold water

- 2 tablespoons lard or olive oil plus more for greasing the pans, as needed

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1 pinch dried bergamot or dried oregano optional

Instructions

- Mix all ingredients well and allow to rest for an hour or so to allow the cornmeal to hydrate before making the mignecci. To make the mignecci, clean the bottom of a ten-inch or similar size cast iron skillet (you will be cooking on the bottom of the pan, and you don’t want debris on your mignecci).

- Invert the skillet on a gas burner or grill, with the bottom facing up, having another pan of equal or slightly less size heating as well. Grease the cooking sides of the pans lightly.

- Take rough ¼ cups (2 oz) of the dough (it should be almost like very thick batter) and, put on the inverted pan, then, take the other pan, and set it on top of the batter to press it down. (remember we’re mimicking cooking between two hot irons, or stones.

- Just like with crepes, the first one or two might not get the correct color since it takes some time for the pans to heat to the proper temperature. The pans should be very hot, slightly smoking, and kicking off enough heat that your instincts should be warning you to be very careful, unless you’re a burn-scarred kitchen troll of a line cook, like I used to be.

- Once you get going, the mignecci will cook fast, 30 seconds or so is all it will take to cook and nicely brown each mignecci. It takes some practice. If the thought of cooking like with the hot pans intimidates you, just make little patties and fry them up, like pancakes, they’ll still taste good after they soften, soaked in the final broth as you eat.

Colleen

I've been making variations on your shoots salad with mushrooms for weeks, so I'm very excited for this new recipe! I'm curious - is there a reason you recommend pureeing the sofrito before browning it? My inclination would be to dice the veg, add the bean water and beans and then purée, so I'm wondering if there's a difference in flavour if you purée first. Very excited to see how it turns out!

Alan Bergo

Hi Colleen. Glad you've been liking the shoots, that was a fun one. I'll peel back the curtain a bit for you. So, traditionally a soffrito is finely chopped, mashed, etc. I wanted to keep the Minestrella as close to tradition as I could, but Jesse and I agreed that the dish needed some color, and, to help vegans and vegetarians making this having a good experience, I used some soffrito pureed with a few of the beans, as pureed or mashed beans are used as a thickener in some versions of the dish. Basically, it helps add a little body and nuance to what basically amounts to "stone soup" without having pieces of carrot sticking out like a sore thumb. I wanted the flavors to blend in, and I wanted a touch of carotene to compliment the red acorn oil we garnished it with, but I didn't want to see a single carrot, as they're not traditional. I have a tic for seeing too many carrots in soups and broths too, often people use too much mirepoix, and then the celery and onion break down but the carrots remain, and give the dish a heavy-handed look....drives me crazy.

Colleen

I see what you mean! The soup turned out a lovely color and was absolutely delicious.

Joe Wiercinski

I've been reposting some of your videos (hope it's alright with you) and thought I should 'fess up. George Delgros, his wife and usually a few of their kids, came to our Jefferson Township farm once in a while in the Fifties to pick wild mustard and dandelions as table greens for their Italian family. They were as noisy and as much fun as our big Polish family. Foraging for wild foods was another commonality between us. My grandmother and namesake Josephine inspired my love for hunting wild mushrooms. La Familia Delgros, I understand better now, was honoring the memory of their ancestors. Delgros family roots had been planted deep in Italian soil before some of them came to America at about the time some of mine emigrated from Poland, probably for the same economic reasons. I don't know anything about Alan Bergo's ethnic past but I do know him online as a Minnesota farm kid who went to fancy pants cooking school and took with him a love of delicious wildlings that can be found in fields and woods, lakes and streams. As a chef, he knows how to present them beautifully on family dinner tables. Wanna see? (Forager Chef link.)

Alan Bergo

Thanks Joe, please repost everywhere you can. Also, I went to business school at Hamline 🙂 Cooking was always my side-hustle, so you'd technically say I'm self taught.

Judith Driscoll

What a useful and intriguing recipe! I'm a little confused about Step 3 in the greens soup recipe. Should the end result of pureeing be more on the liquid side, or just a finely chopped mirepoix? Thank you!

Alan Bergo

Liquid/paste. In Italian this is known as a battuto if it contains fat, or a soffrito. You don't want orange chunks of carrot in the soup, but the color the carotene lends is attractive.

Judith Driscoll

Thank you, chef!

Claire

i loved this post! Keeping this kind of knowledge is so important. most people think the mediterranean diet is what moderns Greek and Italians eat: pasta, cheese, meat, fish, olive oil, but likely meat and fish were consumed only 1-3x times a week and poverty food like chestnuts, polenta, oats, beans, wild greens filled out a large part of the diet. Here is a list from the brochure you kindly attached.

Sonchus oleraceus and S. asprei. Sow thistles

Crepis capillaris: smooth hawksbeard

Ranuculus filaria: fig buttercup, lesser celandine

Viola spp. Violets

Primula vulgaris: cowslip

Campanula trachelium: the nettle-leaved bellflower

Daucus carota: carrot

Symphytum tuberous: tuberous comfrey

Rumex crispus an R. obstusifolium: curly dock and board leaf dock

Reicharidq picroides: common bright eyes, French scorzonera

Hypochoeris radicata: catsear, flatweed, cat's-ear, false dandelion

Plantago lanceolata: Plantain

Silene alba?: white campion

Uric urens and U, dioica: nettles

Papaver rhoes: field or common poppy

Geranim molle: dove's-foot Crane's-bill

Apium noetit/forum?

Taraxacum offinale: dandelion

Foeneculium vulgar ssp. Perineum: wild fennel

Allium vineale: Wild garlic

I would never think of eating sow thistles...they are such noxious weeds where I live.

Alan Bergo

This is really helpful, thanks! I've actually been wishing there were more sow thistles where I roam, I only see a few here and there!

Sylvie

yes, a call to use all the "weeds" (the edible ones!) that grow now, so the dish change as the seasons change. Interesting (to me) to see that valerianella (mache) is in the photo you linked to. I don't think of it as a cooking green. I knew of using Shirley poppy greens (if only because reading Honey from a Weed)... but there it goes again, a big pile of it in that same photo! Their time is over now (at least here in VA) but we have plenty of galinsoga, lamb's quarter, pigweed, dailily flowers, and purslane soon.

Arena Heidi

I love this post and the timing was perfect. As I was weeding the garden today, I was dismayed to be composting so much edible food. I have made many soups using maybe half a dozen of my favorite wild greens, and they would be delicious. Much more delectable than store bought greens. But I never thought of using such huge numbers and also cooking some flowers, too. It would be informative to see lists of all the plants someone used for this. I can see how it easily encourages a festival. Some wild greens are very abundant, and it would be easy to make a lot of this soup. I also appreciate the medical qualities of food like this. Thanks.

Tim Maguire

La cucina povera at its best. Thanks for this inspiring story

Elizabeth Blair

Alan, have you also tried adding the leaves of VA Waterleaf? wild mustard? Nettles when young? I read Year of Wonders recently by Geraldine Brooks set in 1666. It's mentions nettle beer? Have you ever heard of it?

Nina

I like the whole history of your article. I've often made a soup/stew very similar, especially when I would run out of this or that. Of course, not nearly so many greens! I think you are very correct in your statement, "this is a dish born from poverty, from necessity". Many of the finest foods I ever put in my mouth were born from necessity. Thanks, enjoyed very much.