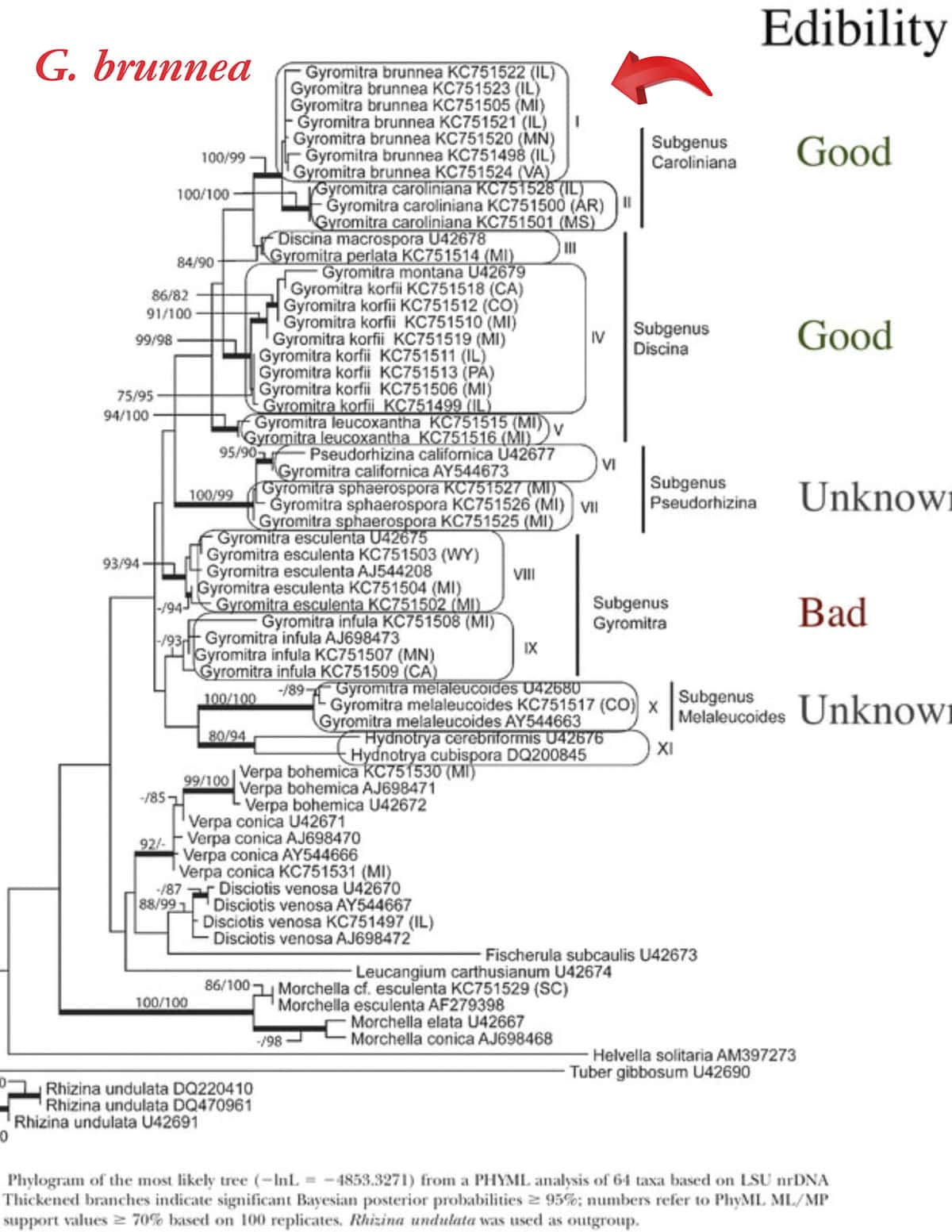

While still a taboo topic for many mushroom hunters, the genus Gyromitra, also known as the false morels, lorchels or murklor, are a world unto themselves worth getting to know. While still labeled as poisonous in field guides, modern research has proved their edibility to be more complex than a simple yes or no. Today we'll take a look at the most common Gyromitra found in hardwood forests where I live: Gyromitra brunnea, also known as the elephant ear mushroom. Even if you never try one, understanding them can make you a better morel hunter.

Background

Like other Gyromitra and many Ascomycetes (the fungal group that includes morels, truffles, scarlet elf cups and others) G. brunnea appears in the spring, specifically in deciduous hardwood forests. Like morels, their function is a little vague, and they may work both in symbiosis with trees, (mycorrhizal) as well as breaking down dead and decaying wood (saprotrophic decomposition).

Like a lot mushroom hunters, when I started foraging I steered clear and was scared to even touch them. Later I learned that even the most poisonous species (G. esculenta and others) were traditional foods in Finland.

My Friend, Finnish Chef Sami Tallberg has a recipe for them in his book, and told me they're essentially the national mushroom of Finland. But, before we unpack their edibility, lets take a close look at their physical characteristics, as if you're new to them it's easy for Gyromitra to all appear similar.

If you're on Facebook, the group False Morels Demystified is a great resource for learning more about the mushrooms in general.

Gyromitra brunnea Identification

G. brunnea grows in hardwood forests in the spring around dead and dying elms, cottonwoods, stumps and downed trees just like morels. The often brick red color of the cap is much easier to spot than morels, so seeing them is a good indication you're on the right track.

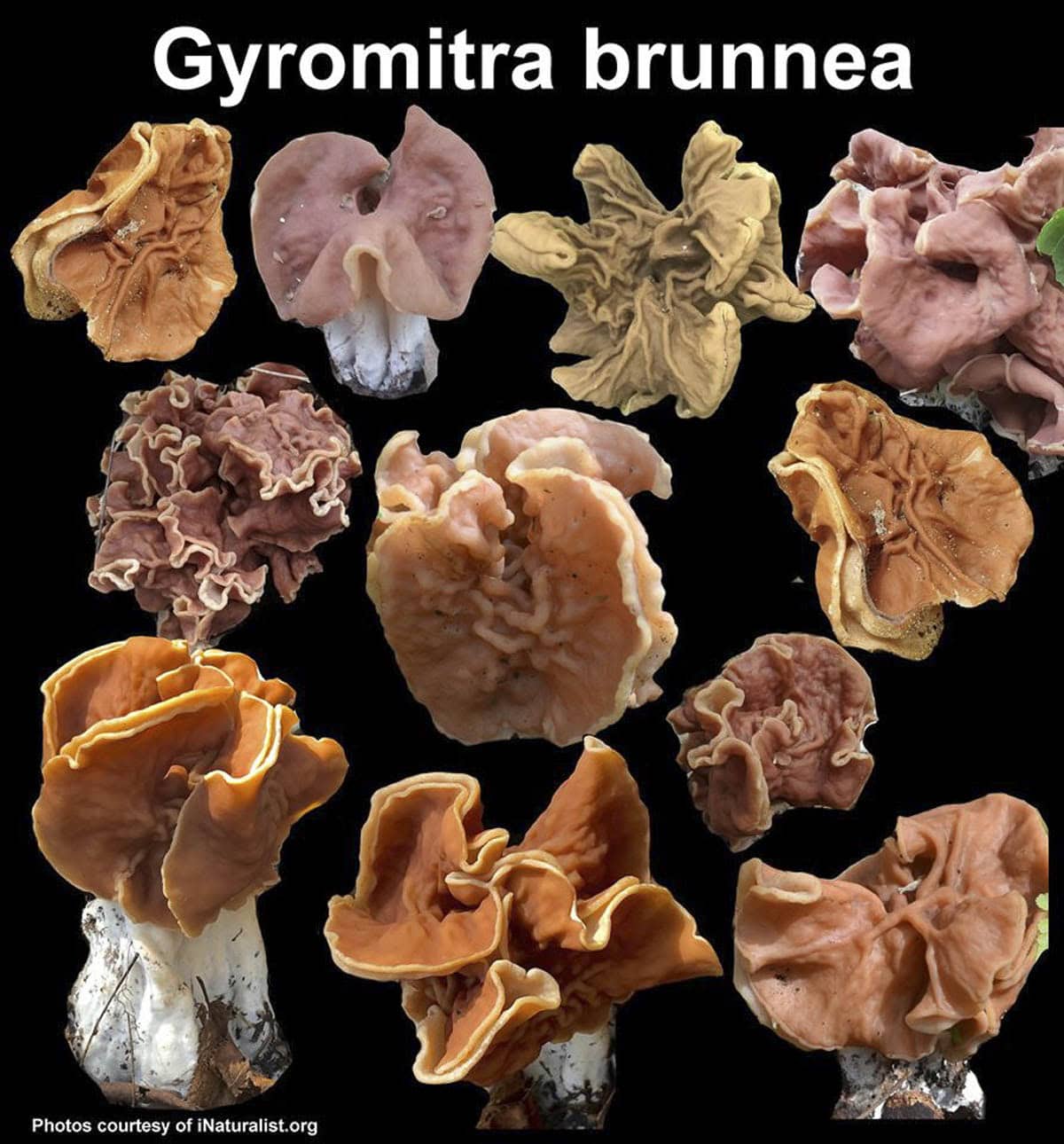

While Gyromitra can vary slightly in shape and there's many different species, there's a few things that set G. brunnea apart. If you can tell the difference between a morel and a gyromitra, identifying them to species isn't that difficult. Here's a few key points:

- G. brunnea has a tan to reddish brown cap. Most G. brunnea that I see are much more red or brick colored than other Gyromitra, with the exception of G. caroliniana, the "Big Red".

- Take note of the tree association. You'll only see G. brunnea in hardwood forests in Eastern North America.

- The G. brunnea I see typically have a distinct, visible stem that may be longer than other Gyromitra.

- The ear reference in the name is apt, and the caps often resemble two or more wrinkled ears pushed together above the stem, although some appear more smooth.

My personal observations aside, there can be some confusing morphological / shape variation. The infographic from the False Morels Demystified group below is a great resource.

Unlike morels, the inside of the stem is chambered, not hollow, and can have some white cottony pith inside.

Look Alikes

There's numerous look alikes, including some not pictured here like Gyromitra infula, and Verpa bohemica, but nothing insurmountable, especially if you don't plan to eat them. It's a bit like learning the differences between different types of oranges or apples.

Gyromitra korfii / Gyromitra montana

G korfii is generally stouter and wider, with the folds of the beige to tan-colored cap obscuring the stem. The stem is also more chambered and prone to housing pill bugs.

Where G. brunnea grows singularly, G. korfii often grows in large, dense clusters. G. korfii also grows strictly with conifers, but this can be a little confusing if they're growing in mixed woods.

Gyromitra esculenta

The species group commonly eaten in Finland is also known to have one of the highest concentrations of Gyromitrin, making it one of the most potentially dangerous. Anecdotally, one harvester I spoke to from the Upper Peninsula recommended driving with the windows down as the fumes coming off a basket of the mushrooms made it difficult to drive.

It has a thinner stem and a much darker reddish-brown cap that's more evenly wrinkled and brain-like than G. brunnea. Like G. korfii, it's a conifer associate. With some other species being essentially harmless and widely available, I don't see a point in eating them, personally.

Gyromitra caroliniana

The "Big Red" as it's known, is one of the best documented edible Gyromitras. As the common name implies it can be enormous, with some mushrooms weighing multiple pounds each. The cap is noticeably reddish-colored and hugs the stem.

It grows with deciduous trees and is most common in the south around the Ohio and Mississippi watersheds. The range of G. caroliniana overlaps slightly with G. brunnea, with the Southern Great Lakes being the northern edge of their range. It, and G. korfii are the best I've tasted, but even so, neither can hold a candle to true morels.

Is Gyromitra brunnea edible?

Yes, but there's a lot to unpack there. The Alden Dirks Study marked a paradigm shift in discussions of this species. Dirks also has a good post on G. brunnea specifically here. Previously it is was assumed all Gyromitra species contained gyromitrin in varying, unknown amounts.

Using a new liquid chromatography process to identify gyromitrin, Dirks proved what many suspected: that some mushrooms in the genus contain next to no gyromitrin, making them just as safe to eat as morels. See the excerpt from the study below.

That said, just like morels, all Gyromitra are dangerously toxic raw and undercooked. To be edible they need extended cooking or par-cooking for at least 15-20 minutes. Pan-roasting or steaming give the best flavor but should only be done with the safer species. Varieties that contain high levels of gyromitrin like G. esculenta need to be boiled, which also removes some flavor.

With al that said, I think the most important thing to consider is the difference between edible and enjoyable. While they often have a comparable flavor (albeit more mild) G. brunnea doesn't even come close to the taste of a true morel and is the least culinarily interesting of the genus I've eaten. As they're easy to spot they're also not very exciting to find.

Since the Alden study was released, there's been excitement among some of my friends and peers about eating Gyromitra. After eating these every which way, I like the crispy texture of the cap, but it doesn't make up for the flavor, which is bland at best.

I even have a few friends who've taken to humorously referring to morels as false Gyromitra. To me, that translates to "I'm not very good at finding morels". Either way, whether you eat them or leave them be, noticing them will make you a better morel hunter.

Matthew Schultz

Please ignore my earlier response. I read the comments. Keep up the awesome work.

Matthew Schultz

Alan,

Have you read the Atlantic’s article about the connection to ALS and the false morel? Sorry if someone already commented. My phone is on the fritz.

Chris Neefus

Please be aware that hydrazine exposure has been linked to neurodegenerative disease (ALS, PSP, Alzheimer’s). Although you may be able to eat Gyromitra with no immediate acute symptoms, the neurodegenerative symptoms can occur later in life. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00754/full

Alan Bergo

Hi Chris, I'm aware of Peter Spencer's work and I spoke with him after he dragged me during his presentations to mycological societies on this topic across the U.S. a few years ago. I think it's great we have tangible evidence of what gyromitrin can do to the body. What I think is even better is that Peter Spencer's work is complimentary to the Alden study-but only pertains the Gyromitrin containing species, and now we finally have irrefutable evidence of which species are safe, and which are not. Spencer is a neurologist, not a mycologist, so it make sense he wouldn't care about flaying out the fine (and this case large) differences between species of one of the most vilified mushroom genera in the world. Spencer wanted to keep the status quo and tell us all Gyromitra are bad, but that is partially because he was doing his research before anyone had figured out a way to find out exactly which Gyromitra contain Gyromitrin and which don't, or in what quantities. If he'd written his work on Gyromitrin after the Alden study I would assume he'd be referencing it.

Mary Alyce L Kronzer

In re Pill Bugs: I found a really nice piece of wood for my terrarium, but it had several Pill Bugs in it. So, I put it in the microwave, and lo and behold - they all came out alive and kicking! I don't believe the microwaves hurt them at all. They are a very ancient species. Thanks for the wonderful information on the False Morels. I live in Northern Minnesota so I find them in the woods when hunting for other s'hrooms.

Alan Bergo

Hey Neighbor. I just got rid of my microwave so I’ll have to take your word on the pill bugs 😆.

Jess Koski

Grand Portage here. I got a free microwave for you 🤣

Thanks for the great articles!

Alan Bergo

Haha thanks Jess, I got rid of it on purpose. New hood vent.

Cheryl Burleson

My dad always gathered these when he was hunting for morels, we never got sick from them, I'm glad they are doing further research on them. I love your columns by the way. Cheryl Burleson

Alan Bergo

Thanks for sharing Cheryl. The tradition of eating these is a lot more common than people think.