Basswood trees are a common, often long-lived tree with a wide variety of uses. One of few tree leaves that are good to eat, the young leaves of the American basswood tree, Tilia americana (and other Eurasian species referred to as linden trees or lime trees) are an underrated edible. Get ready to channel your inner goat: today we'll cover the basics of the tree, harvesting, storing, and enjoying the lettuce-like leaves.

the American Basswood (Tilia americana) is a common shade tree where I roam in Western Wisconsin and Minnesota. Basswoods prefer moist, well-drained soil and in full sun they can grow impressively old and tall. My favorite farm has a few that are multiple hundreds of years old.

In North America, besides T. americana there's also Eurasian linden trees like Tilia cordata and Tilia europea that may be cultivated as shade trees, but they should be mostly found in the South.

American Basswood Identification

If you have a lot of basswoods in your area like me, you'll probably see them everywhere once you get to know them. But you'll need to be east of the Rocky Mountains and the Eastern half of the United States, generally speaking.

In his field guide, Sam Thayer says a most common basswood look alike is probably white mulberry. Both tree leaves are edible, and if the mulberry tree has the non-uniform, lobed leaves separating the two is pretty easy.

Basswood Bark

The bark is grey, with many fissures and flat ridges with age. Young trees and suckers are generally smoother, lighter in color and shinier compared to mature trees.

Basswood / Linden Flowers

Basswood flowers appear in the Midwest around late June and early July. If you get near a tree in full bloom you'll may be able to smell them before you see them. The flowers have a floral, honey-like scent. This is the part of the tree that's dried and sold to make linden tea.

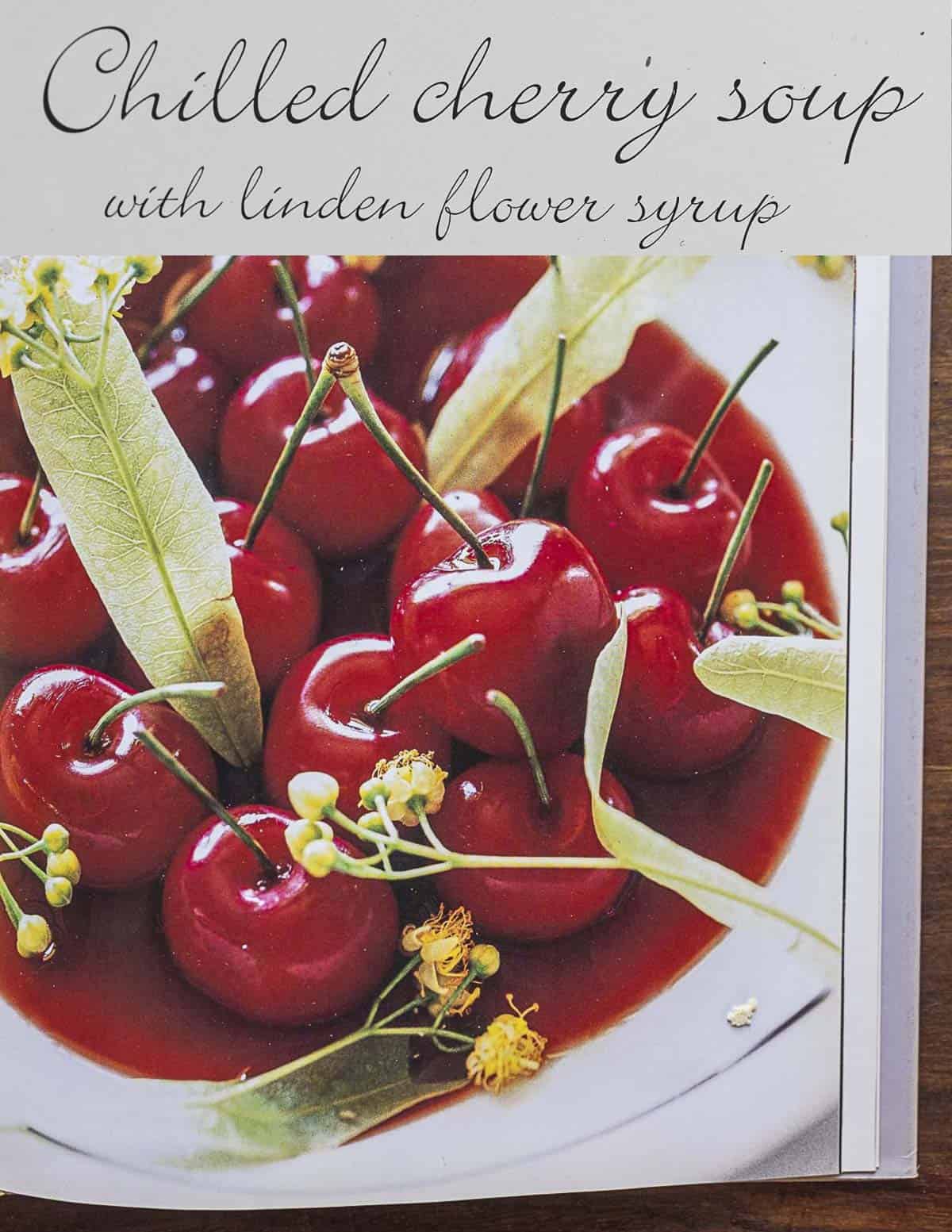

Besides tea, the flowers are also used by some to infuse liquors. French Chef Jacques Chibois uses them like an herb in sweet sauces with cherries.

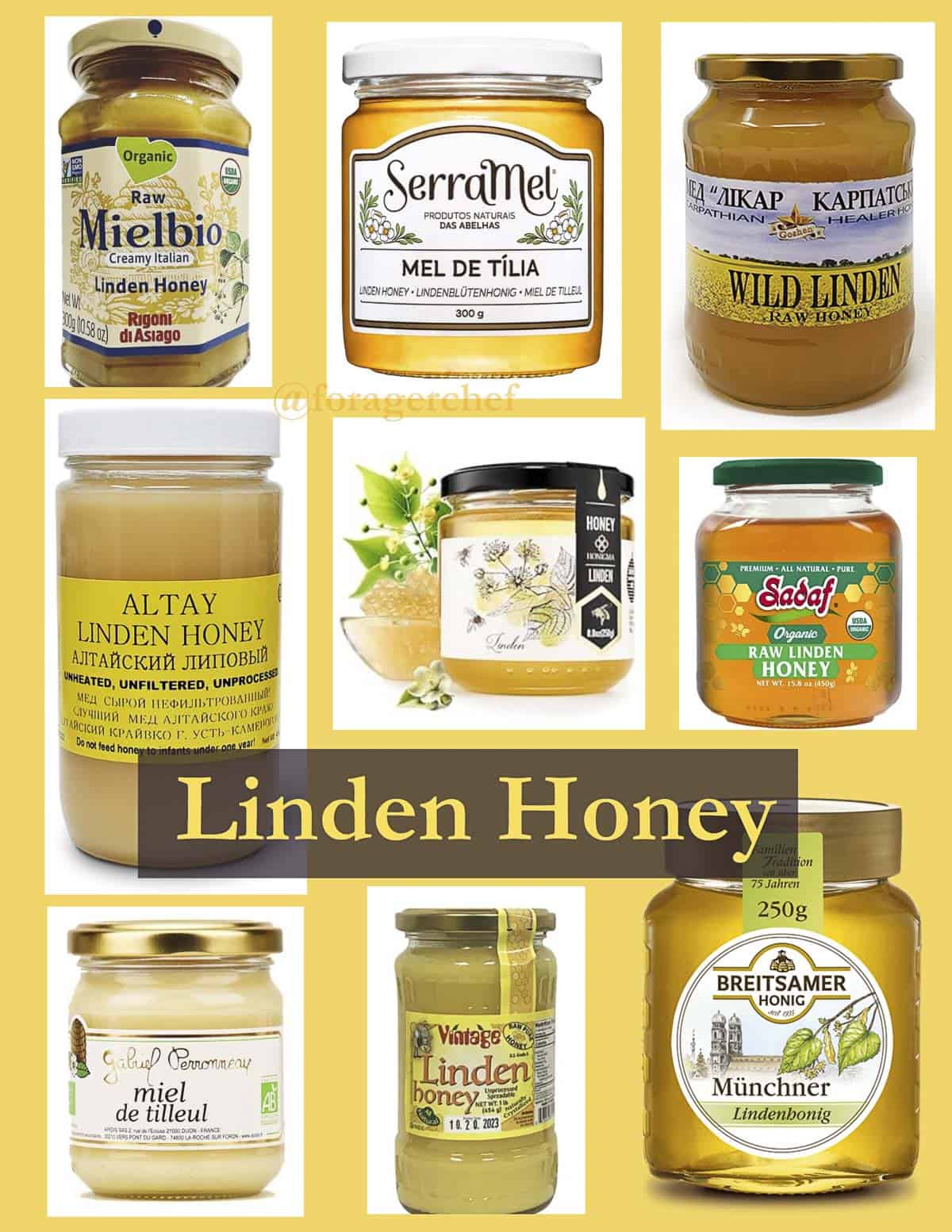

Flowers also produce pollen which bees will harvest to produce Linden honey. Personally, I was surprised I hadn't heard of linden honey until digging a little deeper this week. My friend Linda wrote in to say Linden honey will have "a lighter color and different taste" than your run-of-the-mill wildflower honey.

Basswood Seeds

The seeds are the final edible part the tree makes during the growing season. The small, green, spherical balls are woody and tough, but they can be roasted and sweetened to make a sort of chocolate-esque paste I've used in baking and desserts.

If you missed it, check out my post on Linden Chocolate.

Suckering

Although basswood trees reproduce by seed they have a fast growth rate and often form epicormic sprouts, known as basal shoots or suckers.

Along with the translucent, heart-shaped leaves, noticing the sprouts at the base of the trees was one of the most helpful things for me in learning to identify basswood trees from a distance. The suckers are an easy source of food.

Harvesting and Storing

Early spring is the time to forage basswood leaves, and I often find myself eating them while I hunt morels. Like morel season, basswood leaf season is short, but I'm usually able to pick them for a couple weeks in late April to Early May in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

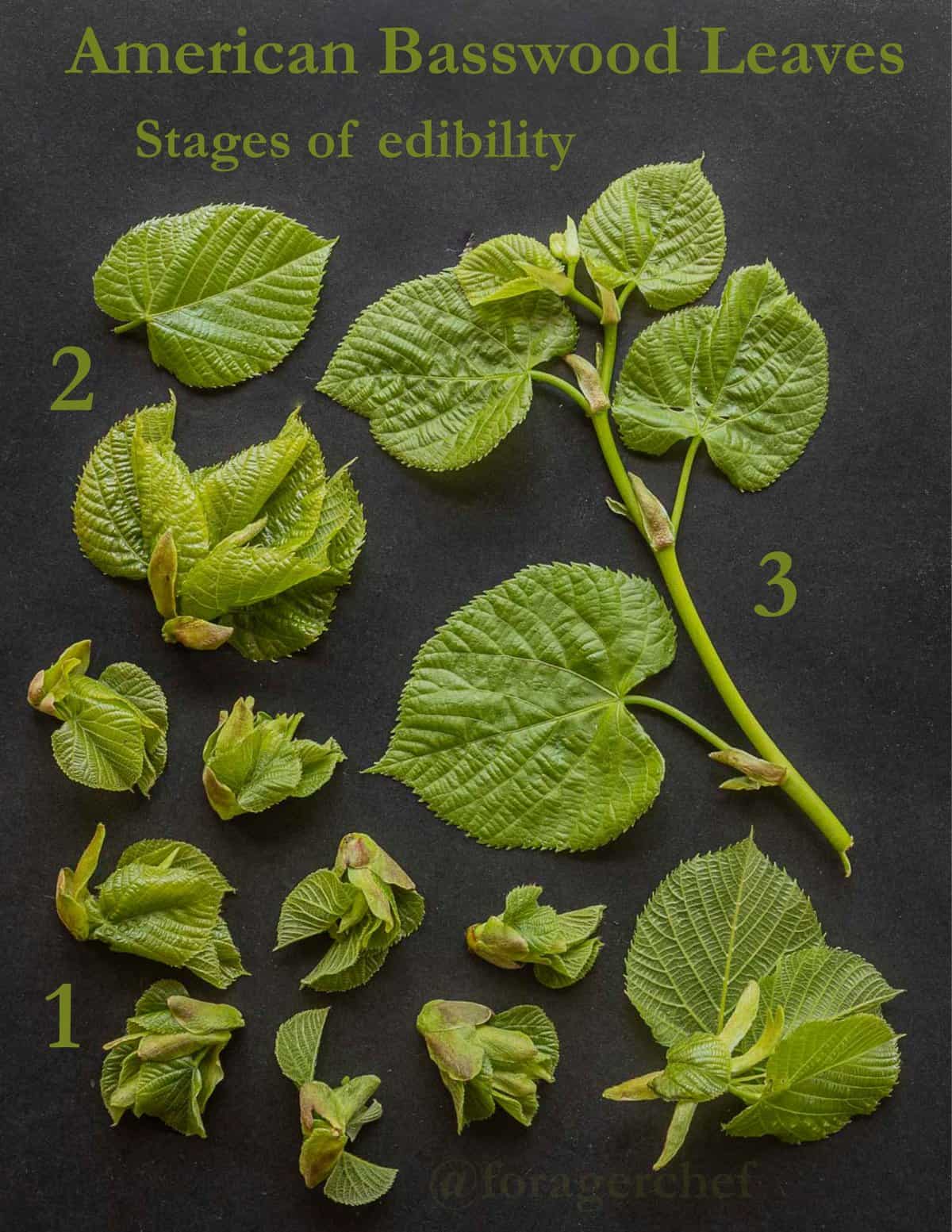

To have a good experience there's a few important things to know. First, the leaves become tougher as they age and only tender, translucent leaves should be harvested. I'll briefly go over the different stages and uses.

Secondly, the leaves are delicate and need to be chilled and stored as quick as possible after harvesting. You'll also want to inspect them for bugs and insects as Japanese beetles and others like the leaves too.

Buds

The first edible form of the leaves is the moment when the young buds are beginning to unfurl. Tightly coiled and crisp, they're reminiscent of miniature heads of lettuce with a mild, pleasant flavor.

This stage is a luxury, and I'll harvest them along with elm samaras by the gallon bag if I have the time. Looking for trees with many suckers can be an easy way to get a bagful.

Young Leaf Clusters

After the leaves unfurl, there will be small clusters of translucent leaves. These can be popped off the tree, stem and all, and eaten like the unfurling leaf clusters.

Leaf Sprigs

The last stage are what I call the leaf sprigs, which is the entire green meristem tissue that would be the yearly growth for each branch. They're not as delicately tender as the others but they can still be used, refer to numeral three below.

Mature Leaves

Mature, dark green leaves are too tough to eat, unless you're a goat or a deer. One thing I often see on mature leaves, as well as some younger ones are galls on the leaf from insect activity. You'll want to make sure the young leaves you harvest are free of those, too.

Storing

Besides understanding the different, brief stages of the leaves, it's important to chill them down as fast as possible in order for them not to wilt. Unlike other greens, basswood leaves don't seem to become refreshed after chilling in cold water.

I keep a cooler in my car with ice packs if I think I'm going to be harvesting fresh leaves, and I harvest a lot of them. When I get home, the leaves are stored in a fish box between layers of moist paper towels or dish cloths. Stored like this, they can keep for a week. You can harvest enough for many meals this way.

Like a fresh flower, you can also keep the leaves fresh by storing twigs directly in water. I use this mostly for garnishes and to keep leaves crisp for the images in this post as it's inefficient to gather whole twigs for food.

General Cooking and Use

Although they're a well known edible among foragers, basswood leaves are underutilized. I suspect it's partly due to the fact that they leaves will quickly wilt if not cooled immediately after harvesting. They're also at their best raw, and I don't cook them, although you can.

I've added the leaves at different stages to salads over the years, and they're great, but there's also a lot more that you can do with them.

Eating through more of the leaves than I ever have this week I was determined to eat them in larger quantities. One of my friends mentioned they tasted like lettuce you'd have on a sandwich, so I did just that. Sure enough, even at slightly chewier stages the leaves can be piled high on a sandwich just like lettuce.

Finding ways to compress the leaves together where they're eaten cold is probably the best way I've found to consume larger quantities of the leaves, and honor them as the wild vegetable they are.

Besides sandwiches, spring rolls are a contender for how I've been able to eat the most leaves in a sitting. I was able to fit 12 whole sprigs in each roll pictured below. It may not look like a lot, but you can watch me count them in the video.

I'm sure you can find lots of things to do with them. If you have more suggestions feel free to leave a comment and share.

Griffin Radulski

Very cool post, thanks so much for this! I have been wanting to plant and coppice T. americana for its leaves since hearing about its potential in a class by Eric Toensmeier, but I don't have much experience eating them in quantity, so this is very helpful and inspiring info. Thanks!

Alan Bergo

Thanks Griffin.

sylvie

Timing is key in harvesting those buds and young leaves. Too late already here in the Northern Virginia Piedmont! But flowers coming soon.

I love linden honey and linden tea as well, but i can be difficult to have pure linden honey as other flowers that honeybees visit are blooming at the same time... unless one is in an area where the dominant flora is linden, and the beekeeper is very diligent in watching her hives and timing the harvest of honey.

And for the sake of clarity, honeybees collect nectar from flowers to make honey. They also collect pollen, but they don't make honey from pollen: they make "beebread", their protein food. Honey is their "carb" food. Of course, there is pollen in raw unfiltered honey, because the hive is not a sterile environment...

Julie

Thanks for highlighting basswood. The leaves are a favorite and every spring I try to introduce more people to them but you’re right, they’re under utilized. When the leaves get larger, just on the edge of too tough to eat, I use them like flatbread, rolled up with hummus, cheese, turkey, etc. Apparently the mature leaves can be dried and crushed for use as a partial flour replacement but I haven’t tried that yet.

Elizabeth Davidson

I planted a tilia in my front yard because I knew they were edible, but now I know how to use them! Thank you!

Clare

I love linden! We call the Europea species lime here in Ireland and I enjoy eating them even through the summer months. I agree the fresh young leaves are the best but I use the large leaves often as wraps for dolmades style snacks as they will happily steam too. I've also used the mucilaginous texture to replicate egg white in a whiskey sour. They're everywhere here so I love an easy pick.