One of the most beautiful and delicious wild plants I've eaten, prairie turnips are a fascinating plant with a rich Native American History. Read on and I'll describe how to harvest and cook these incredible tubers.

I turned off the gravel onto the road--ghosts of tire tracks barely noticeable through summer's tall yellow clover, it gave me the feeling the clearance of my city slicker "little Honda that could" might not be enough for what was to come, the caravan of trucks I was following having no problem.

But, I'd just driven 9 hours from Wisconsin to South Dakota, then nearly to Montana, for a reason. I tried to keep my tires balanced off the invisible grooves worn into the soil so I could see over the grasses. After a few miles of bushwacking, our caravan stopped.

I stepped out into the midday sun, endless prairie in every direction with a strong wind like the Mistral blowing--exactly what I'd come for. We were in tinpsila country, and my friend, ethnobotanist, PhD, and firebrand activist Linda Black Elk had been generous enough to let me come along with her family to the secret patch, at the precise moment in the season when the tinpsila are ready for harvest (Mid-June).

Thíŋpsiŋla, timpsula, tinspila, prairie turnip, indian breadroot, white apple (pomme blanche), the plant has lots of names. Whatever you call them, they're a staple food harvested by the Lakota for millenia.

Ever since I read about them in Sam Thayer's book, I was interested, but for a lot more than just finding something to eat. Tinpsila are a piece of history, albeit a awkward one to ask around about if you're wašíču (white/Caucasian) like me.

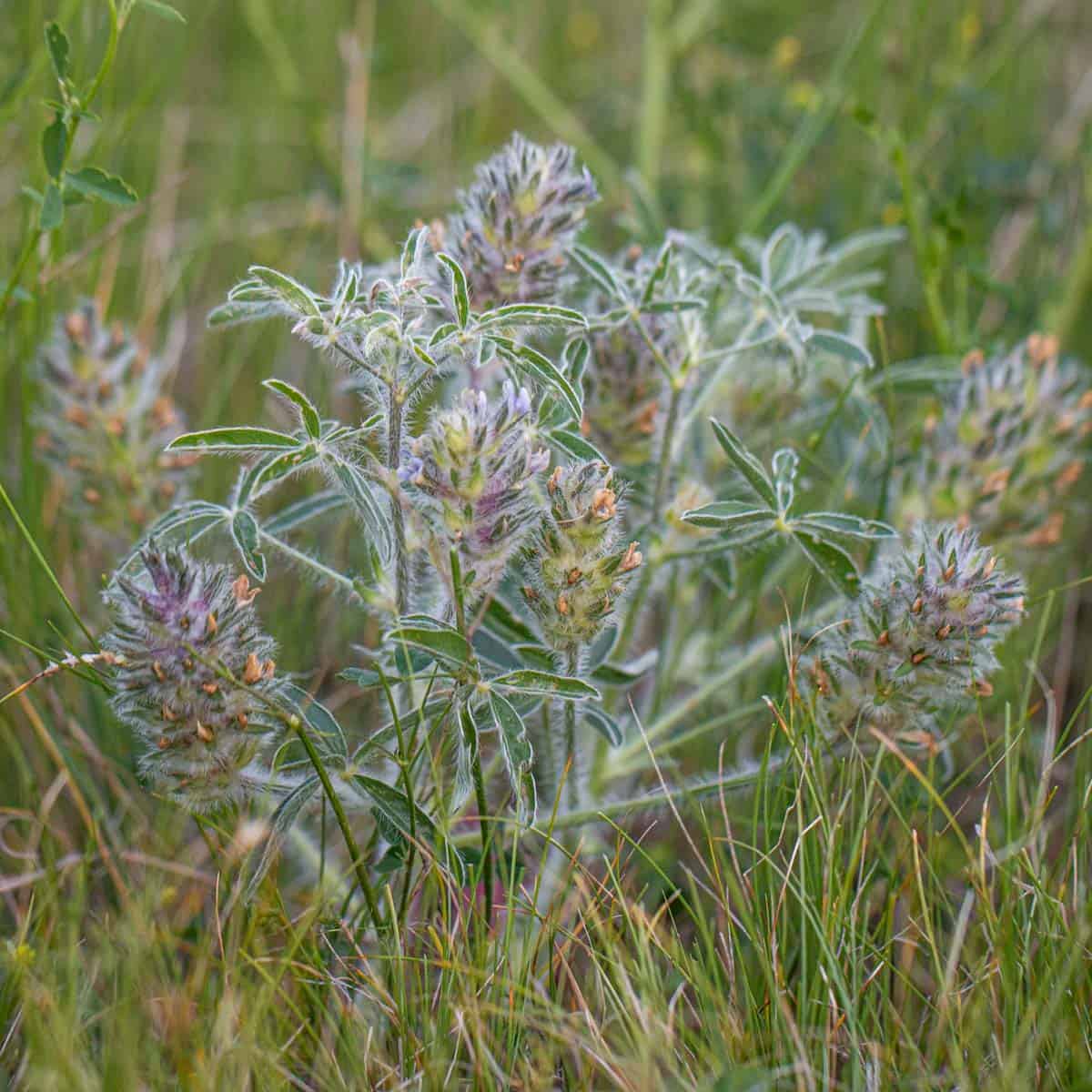

The tinpsila's a beautiful wildflower with a small round root underneath about the size of a chicken egg, or an elongated one which, according to Sam aren't recognized by botanists as a separate species, but are by the Lakota, who call them háska thíŋpsiŋla.

The little roots go a long way. They're naturally dry, but curiously tender root is used for everything from eating raw to thickening soups, cooking as a dried or fresh vegetable, and being used as a flour. As a reliable starch rooted in the bedrock of traditional indigenous prairie foods, it's the definition of a staple crop.

Like a lot of things, timpsila used to be more widespread, and looking online the first year I searched for them I thought I might be able to find some in my home state, I mean, there's lots of prairie in the western portion of Minnesota, right?

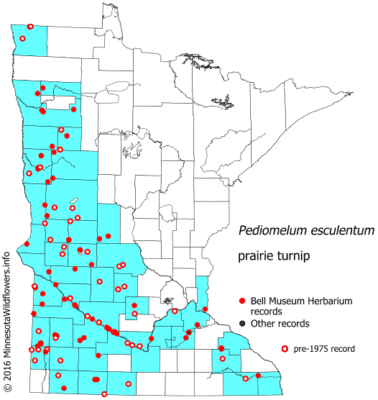

There was lots of prairie in Minnesota. Looking at the sightings map on the Minnesota Wildflowers site, and talking about it with my Dad revealed the unfortunate truth. There's likely still prairie turnips in Minnesota--we have habitat where they could thrive, where they did thrive, but different crops have taken their place.

The best concentration of sightings left were straddling the Minnesota River, and, if we humans could find a reason to farm that river, eradicating the last of our prairie turnips in the process, we'd probably do so.

The year I started searching for them, I ended up discovering some after a few days of hard searching and terrain referencing, but there were so few that I just snapped some stills and let them be. If I was going to harvest some, I wanted enough to make a one of the beautiful, traditional braids to cook with throughout the year. If I was going to gather some, I wanted to do them justice.

Back on the prairie, the first thing my hosts told me was to look out for rattlesnakes. Yep, it'd be fine if I didn't run into any rattlers. Delicious as they are deep fried, the more likely scenario where I end up getting bit and brought to the nearest hospital which was at least 2 hours away seemed like something to avoid. I really didn't want to be that guy.

My hosts scouted around the landscape, then Linda's husband Luke came over, tinpsila in hand, and offered it to me raw. I took a few bites around the woody taproot that stretched through the core. It was good, chewy, with a deep grassy flavor that's hard to describe.

I was surprised that even fresh and wild, straight from the dirt, it was fine to eat, and my mouth watered thinking of dipping them raw in Sam's acorn oil with salt. There's a turnip quality to it, sure, but make no mistake, Thíŋpsiŋla are their own creature entirely. Calling them a turnip is like calling a paw paw a banana.

Everyone grabbed a spade and got to work, spreading out to give each other room to hunt. Primed from my first solo hunt, I scored right away, only to find out the plant I thought was right was wrong. There's a look alike. Silvery scurf pea (Pediomelum argophyllum) a cousin also in the legume (Fabaceae) family that's more numerous, and likes the same habitat has very similar leaves, but lacks the tell-tale hairs of the real deal.

Linda said the Lakota say the scurf pea protects the tinpsila--a romantic way of describing indicator species I kept repeating in my mind as I hunted. Sure enough, here and there near the scurf pea, I'd see the tell-tale fuzzy arms and flower stalks of the prairie turnips, and, when I found a good one with mature flowers, I'd get to work.

I made a mistake in my equipment though. The midget shovel I brought, fine for loose, wet soil, was too small, and in areas where the ground was more firm, it turned digging the roots into a crucible, like prying carrots out of hard gravel.

The ideal method is that you uproot a good amount of soil like a flower pot (using a big spade you can jump on) carefully twist off the tuberous root and the long taproot which will eventually be braided to dry, then put the soil back down like nothing happened, with the mature flower stalk still standing upright.

A sustainable harvest dating back millenia

Here's where the magic comes in. Modern foraging ethics and pick-shamers tell us that digging plants is wrong, and unsustainable. I do avoid digging certain things, since I know it will kill the plant, angelica roots, for example. The prairie turnip though, at least in the vast spaces in what's arguably the epicenter of it's preferred habitat (short-grass prairie) seems to be a little different.

As I understand it, if root is harvested when the seed head is mature, and the seed head stuck back in the ground, eventually, the seeds, even on only slightly-mature plants will continue to ripen, and eventually blowing away on the strong prairie wind, as a tumbleweed.

I was fascinated as Luke explained the process, and, sure enough, the evidence of a previous year's seed head being near the fresh plants was obvious. I'd wager 50% of the timpsila we dug had an old seed head near them that was visible.

Luke also said that knowing how the wind blows also helps in the hunting (see video above--the wind never died down). He told me to think like a tumbleweed, more or less, and, sure enough, imagining where I would go as a blowing, tumbling tinpsila was helpful. I'm used to following trees, rooted things like landmarks I can count on, so trying to imagine how the wind would blow seeds was a novel way of thinking.

I think the tumbleweed aspect is a great example of a plant evolving to it's surroundings, and the closest analogy I can think of is the similarly open pine barrens, and how the plants there rely on fire, the jack pine cones staying dormant until a fire comes through. The cones are primed for the heat of fire, and then they open up, getting a leg-up on other plants by being the first to spread seed. Nature's designs are so intricate.

After an afternoon of harvesting, we called it a day and took a dip in a frigid, rocky lake--perfect for quenching sunburns. Once we got back to camp, it was time to process the day's harvest. The Lakota method of drying uses the long taproots to craft the grand finale of the harvest: an intricate tinspila braid that gets hung to dry. It's one of those pieces of ancient knowledge I love so much, function only equaled by it's beauty.

Traditional Timpsila Recipes

Of course I had to ask about traditional methods of cooking tinpsila. Luckily Grandma Candace (who steadfastly peeled tinpsila while we harvested) was more than happy to indulge me. Of course, our quick talk about traditional methods only exposed more rabbit holes to go down. The first thing she mentioned was that the roots shoot be cooked with bison guts, which we figured must be tripe, preferably not exquisitely cleaned.

The second thing that came up was bapa soup/stew, also known as papa soup, made with bison jerky, dried corn or hominy, and tinpsila, and maybe some wild onions. Inevitably wasná was also mentioned, the famous dried meat ground and mixed with fat or tallow, dried berries (I assumed serviceberries were used but chokecherries were definitely the berry of choice here) and sometimes ground tinpsila.

Wašíču was another thing I had never heard of, a sort of salt-free dried bison hump fat that might be used in the wasná. Needless to say, I'm talking to some of my bison farmer friends to get some hump fat--we'll see how that works out.

Knowing that the roots are usually re-hydrated, I started with a simple stew. I browned some venison with wild onions and dried ramp leaves, then added the fresh tinpsila and a few sunchokes at the end for variety. Once the pot started to simmer, the smell of tinpsila filled the room, and I couldn't stop snacking on them while they were cooking. The roots both soak up the flavor of broth, but also add their own aroma to it at the same time.

The aroma is hard to describe: grassy, earthy, pleasant, and crying for meat juices. Even cooked fresh, they keep a bit of chew, but it's a good chew that lets you know what you're eating is special. With older roots, you might want to remove the tap root, or make sure to cut them into smaller pieces for easier eating to they can fit on a spoon, but small tinpsila are tender, soft treats.

As an aside, I've cooked a lot of different vegetables, but the prairie turnips do something I've never seen any tuber or root do before. Not only do the roots plump as they cook, they literally inflate to about double their size cooked from fresh--something that your average turnip won't be doing.

Adopt a Prairie Turnip

You might be wondering "sure, this is a cool plant, but how could I ever get some?". A lot of you live near me in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin, and the Dakotas, etc. If you do, you're probably living in the range of this plant, especially if you're in any kind of prairie.

As I mentioned, prairie turnips used to be a lot more widespread, but looking at the image above from Minnesota Wildflowers will show you a glimpse of their future (at least in Minnesota). The sightings with white in the middle are pre-1975, and it's probably safe to assume a lot of them are gone. But, Prairie Moon Nursery sells prairie turnip seeds, so you can try to grow your own. This beautiful plant, and all the history woven into it deserve to be remembered.

Timpsila Recipes

Dried Venison Stew with Timpsila (Bapa Wohanpi)

Equipment

- 1 crock pot or gallon size soup pot

Ingredients

Meat and stock

- 8 cups venison trotter bone broth

Dried ingredients

- 1.5 oz Dried squash

- .5 oz dried onions leeks or ramp leaves, crumbled

- 4 oz dried hominy

- 3 oz dried timpsila about 22 small timpsila

- Kosher salt and pepper

- 2 oz reserved cooked venison trotter meat and tissue, finely minced (optional-or substitute 1 oz dried meat )

- 4 oz dried venison / Bapa / Papa

Instructions

Soak the hominy and timpsila

- Combine the hominy and timpsila in a bowl and cover with boiling water by ½ inch and leave overnight. The next day, cut the timpsila into ½ rounds or bite sized pieces. Reserve the hominy and timpsila in the water.

Soak the squash and dried meat

- Put the squash and dried meat in a bowl and add an inch of boiling water (you don’t need to cover them as they won’t take a lot to rehydrate.

- Cut the squash and dried venison into bite-sized pieces, then cut the timpsila into ½ inch slices.

- Put the timpsila and corn into a soup pot, along with the dried onions, add the venison trotter broth, along with the rehydrating liquids, bring the mixture to a simmer, cover, and bake at 250 F for 3 hours, you can also simmer it covered on the lowest heat.

Add the meat and squash

- Next, add the dried meat and squash and cook for 30 minutes more along with the minced hoof fat and leg meat, cooking until the dried meat is tender and tastes good to you.

- Finally, add the chopped hoof fat and leg meat. Double check the seasoning for salt and pepper, adjust as needed, and serve.

- It’s great with a splash of lemon juice to lift it, as it’s a very rich soup.

Notes

Nutrition

Turkey Stew with Prairie Turnips and Parched Corn

Equipment

- Crock pot

Ingredients

Stew

- ½ cup tepary beans

- ½ cup parched Flint corn

- ¼ cup good Mexican hominy

- 12 oz turkey thighs roughly 2, skin-on, bone-in

- Kosher salt and pepper

- 5 large guajillo chilies or a combination of other chilies, like ancho or pasilla

- 6 cups hot chicken stock either homemade and unseasoned, or use water

- 12 medium dried prairie turnips

- 1 large yellow onion

- 5 large cloves garlic

- 2 tablespoons animal fat like bacon grease, chicken schmaltz, or lard

Garnish suggestions

- Sunflower sprouts

- Chopped yellow onion

- Radishes

- Shredded cabbage

- Avocado

- Lime wedges

Instructions

Prep

- Season the turkey thighs with salt and pepper liberally, then allow to rest uncovered in the fridge overnight, skin-side up.

- Cover the prairie turnips and parched corn with boiling water to cover. Cover the beans with 1.5 cups room temperature water. Allow the ingredients to soak overnight, room temp or in the fridge, either is fine.

Building the stew

- The next day, cut the prairie turnips into ½ inch slices, removing the remaining string of taproot in any as you cut. Toast the chilis in the oven at 325F for 10-15 minutes or until fragrant, then allow to cool. The chilies should be crisp and brittle, break the stem off, discard as many seeds as you can and reserve.

- In a 10 inch saute pan or skillet, heat the oil and brown the turkey skin-side down. Meanwhile, crush the dried chilies, then puree smooth in a blender with the hot stock or water. Deglaze the chicken stock with a splash of water, scrape up any brown bits and add to the chili-stock mix.

- Combine the turkey thighs, corn and timpsila, along with their liquid, the chili-stock puree, onion and garlic in a crock pot and cook for 6-8 hours on high, or until the parched corn has started to burst and the beans are tender. Remove the turkey thighs after 1.5 hours, chill, remove the skin and chop fine, then cut the meat into pieces and reserve with the skin (adding the skin is optional but adds richness).

Finishing

- To finish the soup, add the chicken and skin to the pot. Judge the level of liquid in the pot and refresh the ingredients with some extra stock or water if the soup is getting dry. Double check the seasoning for salt, pepper, and spiciness, adjust until it tastes good to you, and serve with the garnishes on the side.

References

The Native American Healer Reviving the Medicine of Her Ancestors

Incredible Wild Edibles, by Sam Thayer

Li

Would this grow in the warmer, drier side of Oahu, Hawaii?

Alan Bergo

I can't speak to that.

Alison Krohn

I saw some this morning while pulling mullein in a degraded prairie that is our pasture in northern Nebraska. Thank you for describing how and when to harvest them. I've harvested the seed before and sold it but I think I'll try growing it along with some scurfpea. We have both here.

Alan Bergo

You are in perfect country for them.

Ellen

Love this post. I am SO jealous! I've wanted to forage for and taste tinpsila ever since I first read about it in Sam's book. I guess I'll have to make a special trip someday. Thanks for this.

Nina

Oh my goodness. This is simply wonderful!!! I do not live in a prairie area and had never even heard of tinpsila but these are super cool. I'm going to give them a try! I tried Trail of Tear beans just for the history of them and am hooked so this is so exciting! Can't wait to order and receive my seed. Thank you for sharing your adventure.