Sometimes called the "grocery store of the woods" cattails are a widely available edible plant that even non-foragers know. These plants have been used for eons around the world, are easy to identify and offer multiple harvests throughout the growing season. Today we'll take a look at cattails, and how to harvest and work with every edible part I know of.

Background

A common sight in wet and marshy areas, ditches ponds and lakes, the common cattail (Typha latifolia) is a perennial plant native to North America and widespread throughout the continent. Besides its well-known use as a food plant, the leaves and other parts were heavily used by indigenous people as a textile crop for weaving baskets, mats, and other uses.

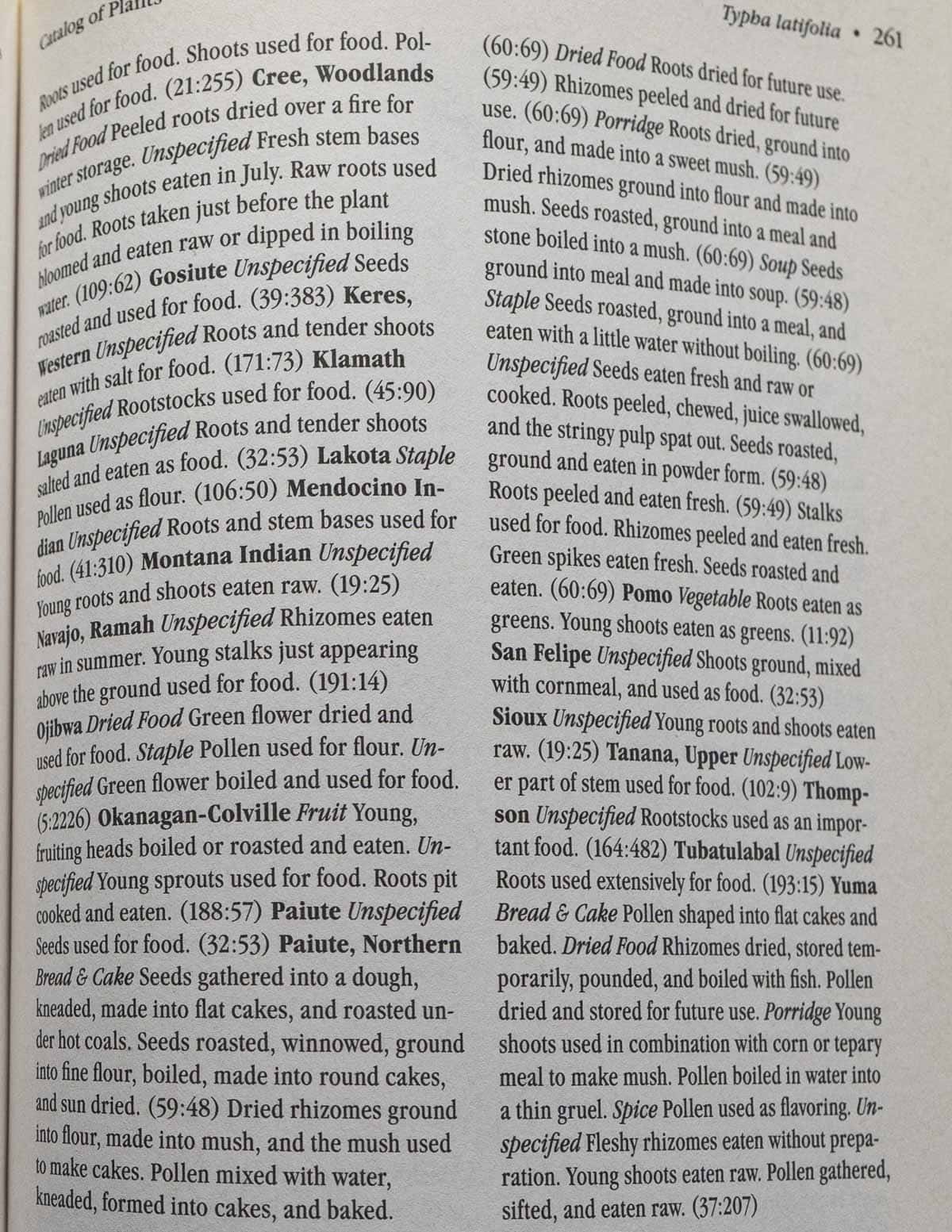

The entry of culinary uses in Daniel Moerman's Native American Food Plants on Cattails is one of the longest in the book.

While there's many plants in the genus Typha around the world I'm only going to discuss the two most common ones I see in depth. Besides T. latifolila, there's also T. augustifolia or lesser bullrush, which is generally smaller, with narrow leaves, stalks and rhizomes. If it's native or not is debated, but Sam Thayer lists it as native in his Field Guide to Edible Plants of Eastern North America.

As T. augustifolia is generally thinner and less robust, it's inferior to T. latifolia as a food plant, but also confusing as the plants will hybridize, making ID difficult. In North America there's also the southern cattail, Typha domingensis, which I haven't tried.

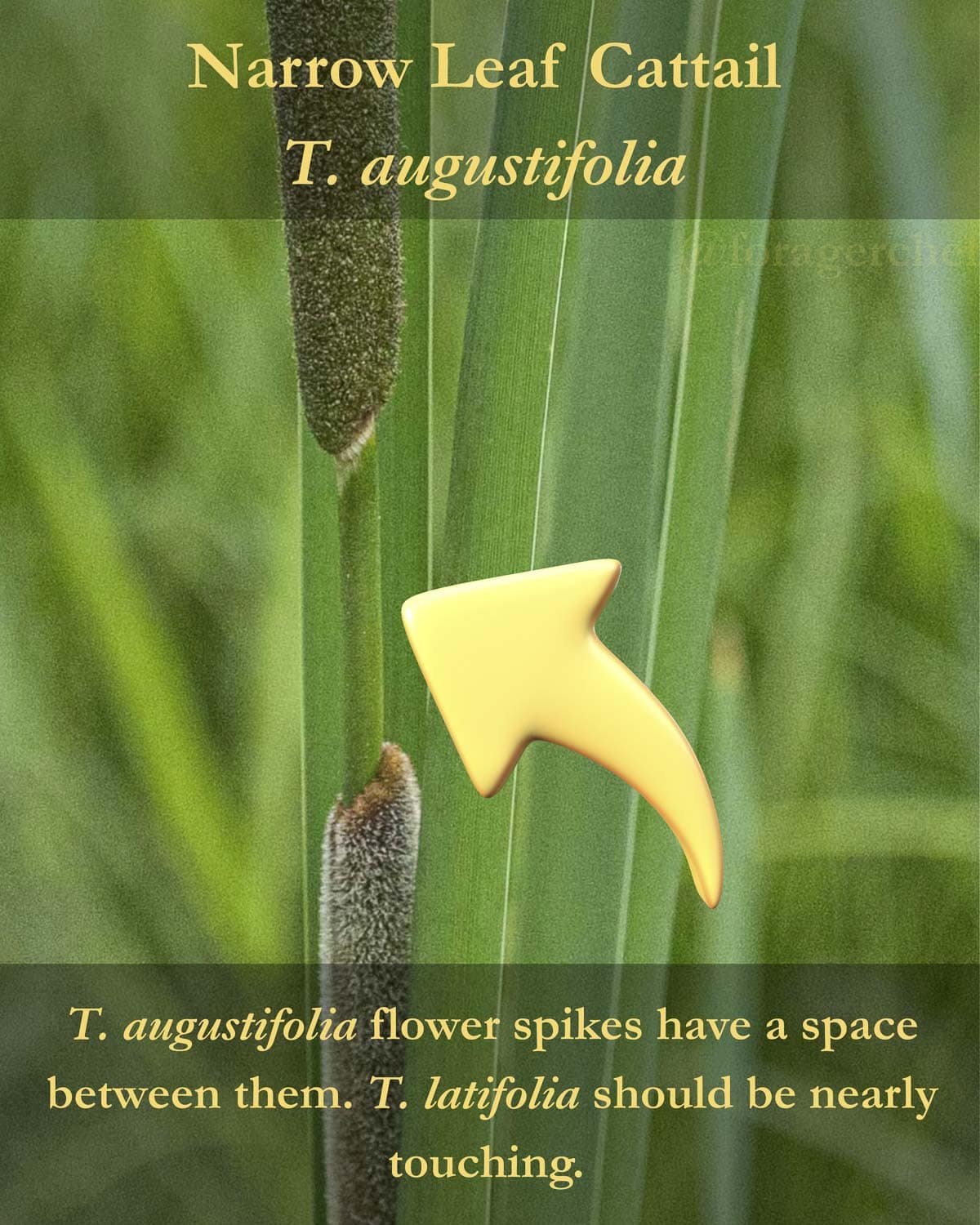

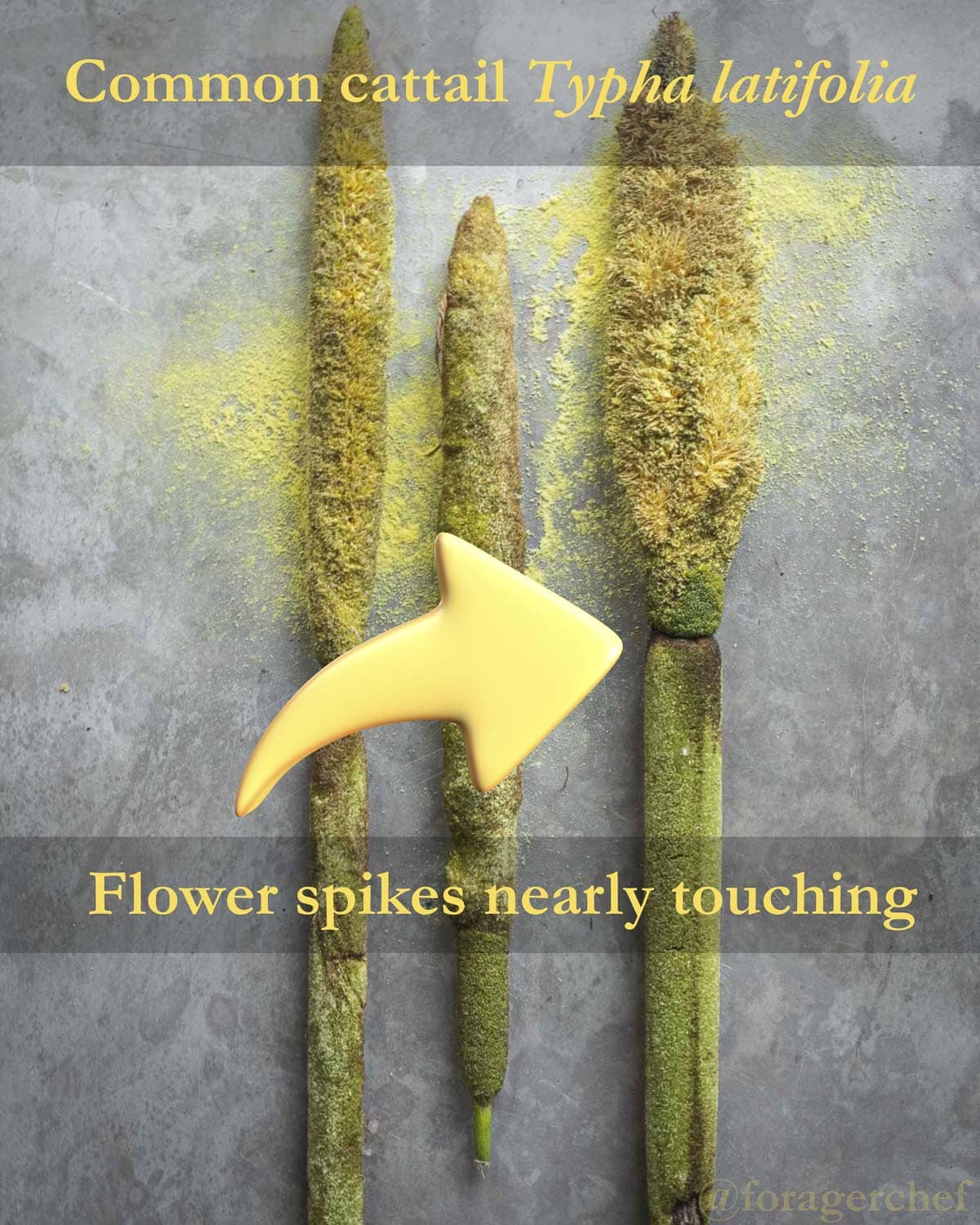

One quick way to separate the T. latifolia and T. augustifolia besides general size at a glance is noting if there's a separation between the male and female flower spikes. T. augustifolia has a space between them, where T. latifolia should be nearly touching.

Safety

Water plants like cattails, watercress, and others are well known for accumulating toxins, so I make sure to only harvest cattails from places that I know are clean and safe. I typically harvest from wet areas on private land or other places I know are free of chemicals. While those cattails in the ditch might look attractive, it better be a clean ditch, meaning I can't see a farm field in any direction.

Cattail's Edible Parts

As a food plant, cattails have numerous edible parts available throughout the growing season you can try. I'll cover harvesting and preparing each of them, roughly in seasonal order they appear as best I can.

Cattail Allergy / Sensitivity

Like plenty of other foods, some people can't tolerate eating cattails raw. To hedge your bet, serve small portions mixed in with other foods like the salads and other dishes I describe in this post, and cook them briefly.

Shoots / Cattail Hearts

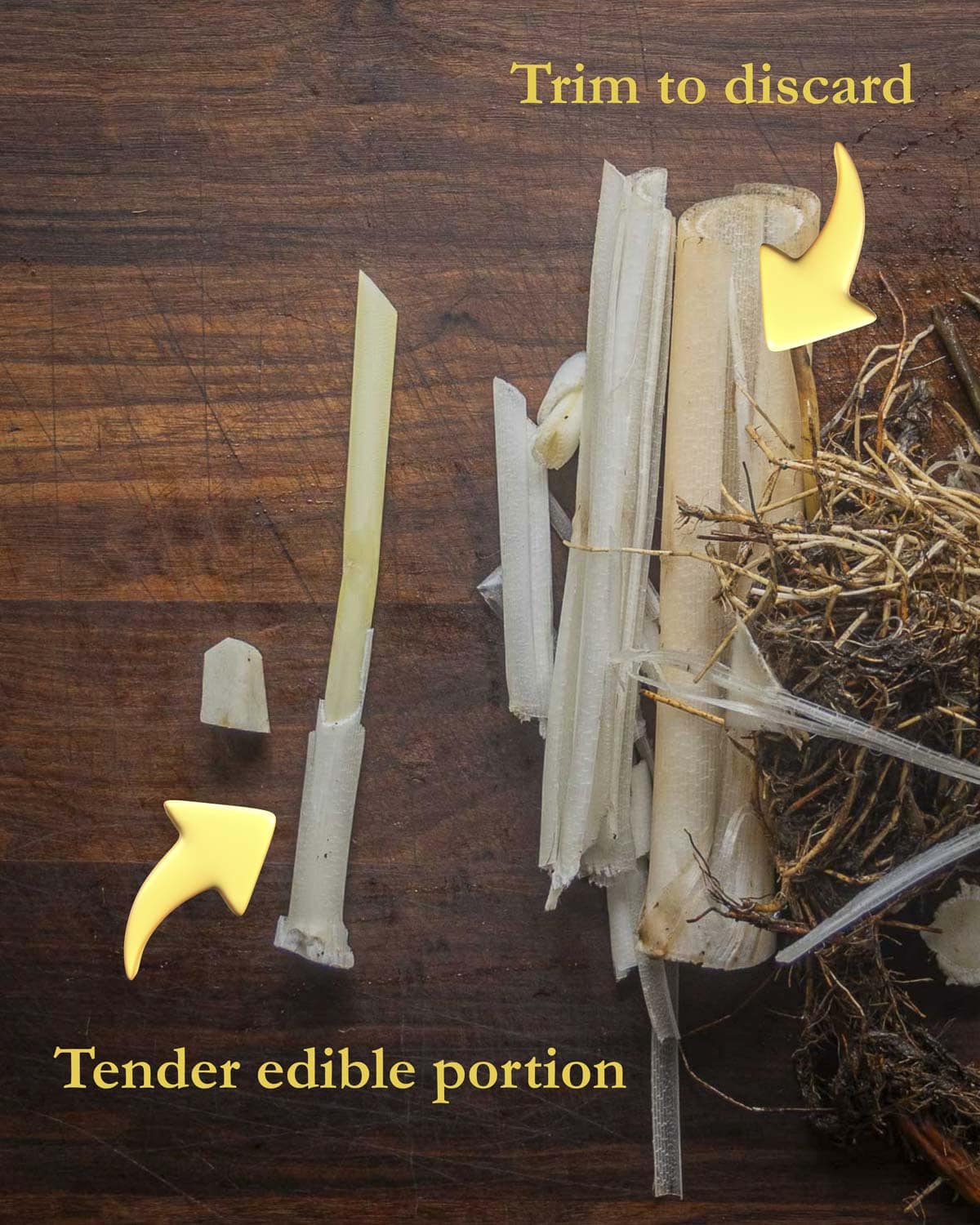

The first annual harvest from the plant is the shoot, or heart, which is the inner, tender portion of the leaf cluster. It tastes reminiscent of tender, crisp cucumber. I usually harvest them from around early to mid June by simply yanking them from the muck. You'll get the best yield before the flower spikes appear.

Species and time of year is very important here for you to get the most food. T. augustifolia and hybrids are thinner and more lackluster than T. latifolia. However, any species you harvest will have a large amount of woody, tough trim that needs to be discarded. I demonstrate removing the tender heart from the leaf clusters in the video.

Cattail hearts can be eaten raw, but eating more than a few nibbles can cause a mild scratchy throat irritation. I find this is much less pronounced after the tender hearts have been seasoned and mixed with other vegetables in a salad.

By far my favorite is the hot shoot salad I made for lunch during my residency at the Milkweed Inn with Chef Lane / Illiana Reagan. The recipe will be in my next book, due in 2026.

Cattail shoots are also great cooked and I've been making a slightly tart, savory relish from them to garnish dishes for years now. One of my favorite ways to use it was on swamp pasta: duck eggs noodles with pollen butter sauce, cattail relish and marigolds.

Cattail Flower Spikes

During late June where I live the green flower spikes will appear. These are easy to miss, and I chased them for a few years in order to get the cattail "hat trick" of all the edible parts I wanted for this post.

One thing that was confusing about flower spikes at first was that there's two portions on the plant. The male flower spike at the top, and the female flower spike below it. The female flower spike is of inferior quality, so I only recommend eating the top male spikes for the best experience.

Like the hearts, it's important to get the flower spikes at the right stage for eating. Once they start to swell with pollen they're past prime. The flower in the middle below is what I look for to eat.

If you've ever heard people mention "cattail on the cob" they're talking about flower spikes.

They're best cooked, and often steamed, with the tender flower portion nibbled from the stem.

If you find large amounts, the flowers can be stripped from the stems and the tender green material can be added to breads and baked goods like you would zucchini.

Pollen

Late June to early July the flower spikes fill with pollen. This is probably the easiest part of the plant to find and harvest beside the hearts. It has a mild, yeasty flavor comparable to pine pollen. As pine pollen is much easier to harvest for me I typically skip cattail pollen.

As cattails grow in wet areas you may need waders to reach them in order to get enough to cook with. If you're lucky enough to find a patch flush with pollen that's accessible, you can use a bag or a milk jug with a hole cut out int the top to shake the pollen from the flowers into the same way I harvest pine pollen.

You can also strip the flower head material and sift the pollen out if you only have access to a few plants. Sift the pollen and store it in the freezer and it will last for years.

Khirret

One of the most interesting culinary uses of cattail pollen is a traditional food in Iraq. The pollen is used to make a sort of candy called khirret (pronounced khee-ree-at) also known as boori. There's a few articles online, but most draw from a very informative article from Nawal Nasrallah. It's a fascinating read.

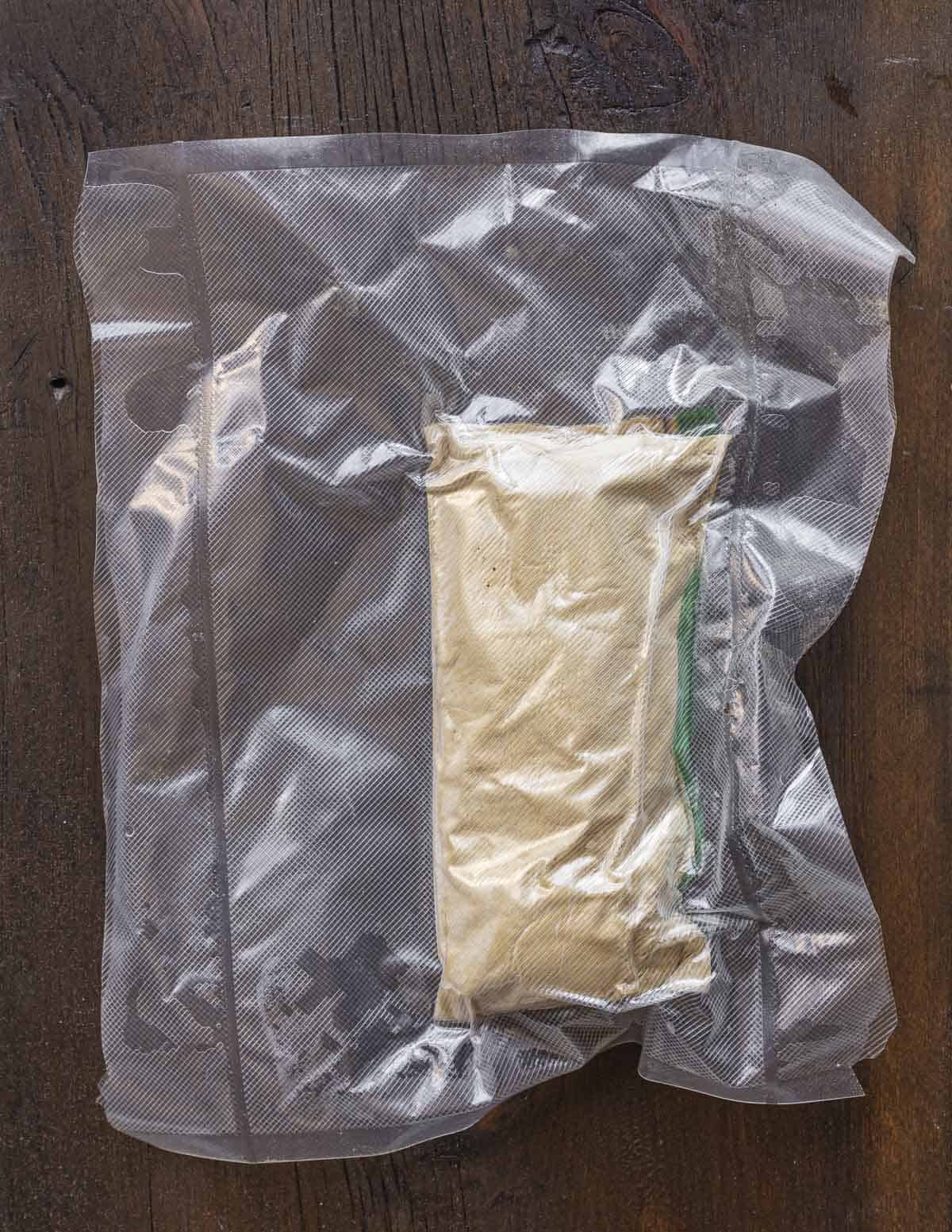

Essentially the pollen is mixed with sugar, wrapped in muslin and steamed in a cone shape. Pieces of the large, yellow cones are chipped off and sold as a street sweet.

I spent two seasons trying to create the candy and found it pretty difficult. Pollen is precious, and the small test batches (failures) I made quickly depleted my supply year after year. After some expensive trial and error, I managed to make a hybrid recipe you can use to make in a small batch in 2020.

The method I came up with involves vacuum sealing or steaming ground sugar with pollen and a small amount of mashed potato to prevent it from breaking your teeth. It's a really fun project, but unless you can get large amounts of pollen I recommend trying my pollen truffles first.

If you want to try it, take ¼ cup (15 g) sifted pine or cattail pollen, mix with ½ cup (90 grams) turbinado sugar ground in a spice grinder. Add 1 tablespoon (15 g) slightly overcooked, riced potato. Form into a log, vacuum seal and cook at 180 F for 2 hours. Or steam it on lowest heat in a closed container, with the pollen wrapped in muslin for 1 hour. Cool completely, chip into chunks and enjoy.

Just like pine pollen, cattail pollen also makes a great addition to baked goods like cookies, quick breads and pancakes. Use no more than 30% of the total weight of flour when adapting recipes. It adds a fudgy, custard-like texture and attractive yellow color. For more ideas, see my post on cooking with pollen.

Lateral Rhizome

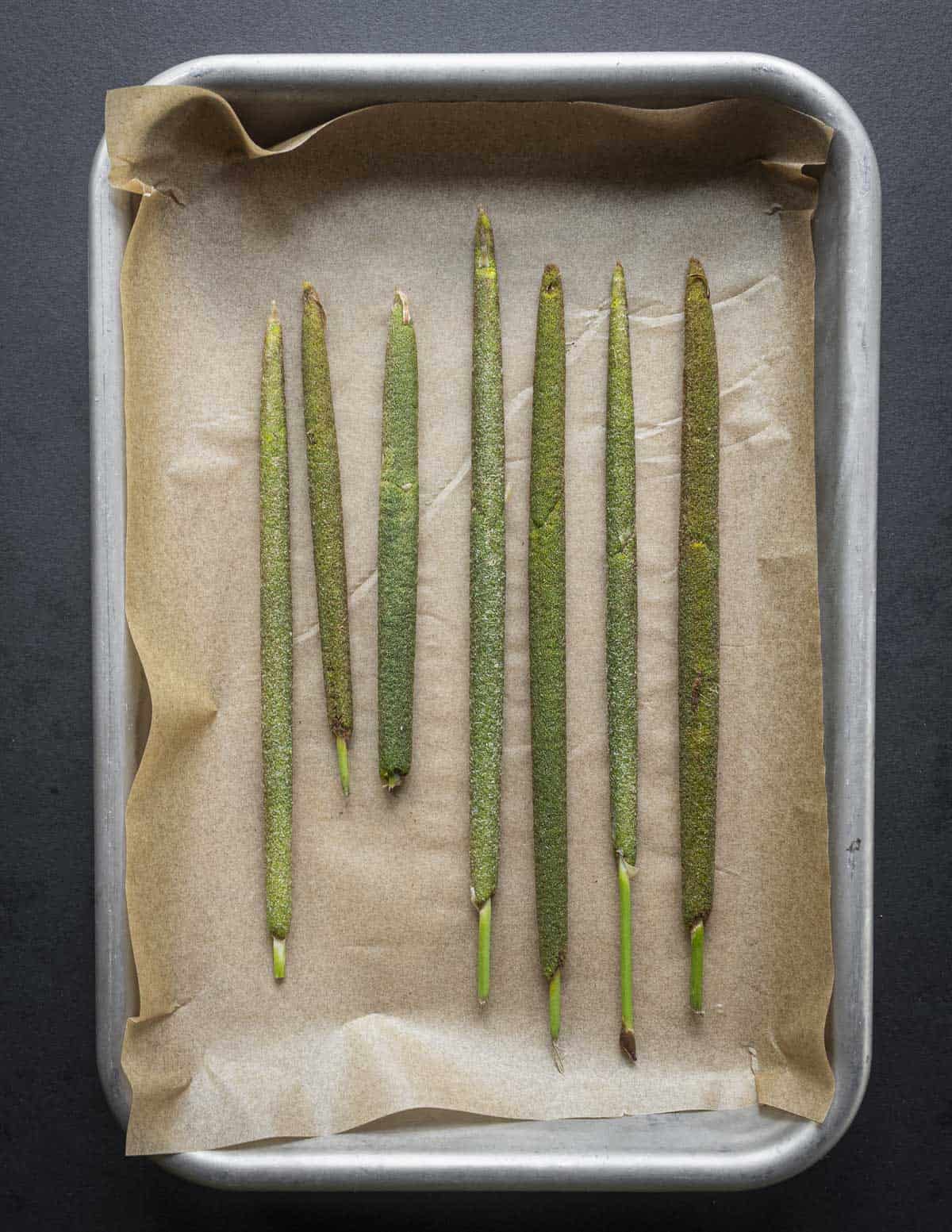

The finest part of the plant, as well as one of the more difficult to harvest. Laterals, as Sam Thayer calls them are a luxury. There's something romantic about the pearly white ivory tusks emerging from a dark lake filled with leeches-the latter of which is why I've mostly cook with them after Sam's pulled them for me. They have a wide window for harvesting and I've eaten them from June-August.

On a rare occasion I've been able to yank up a cattail and discover attached lateral shoots, but the best way to do it is to feel with your hands under water and yank them from the muck.

If you subscribe the Outdoor Channel you can see Daniel Vitalis and Sam Thayer digging them from the muck for Daniel's show Wild Fed. It was so deep they needed to hold their breath with their heads under the mucky leech water. Thankfully I just got to cook them.

Rhizomes are wonderful raw or cooked. They have the subtle cucumber-water chestnut flavor of the hearts, with none of the stringy fibers. They're crisp, but more tender than a radish, refreshing, and crave-able.

I try to do as little as possible to them. Slicing into ¼ inch pieces and tossing with a salad of greens, herbs and smoked trout with olive oil, lemon and herbs is a dish worthy of a five star restaurant, and how I served them on Daniel's show.

Rhizomes and the Slotsm

Finally, the most obscure edible parts of the plant. The rhizomes are very different from the lateral rhizome portion as they're soft and stringy. While you won't be frying them up, they can be crushed to extract culinary starch. There's numerous accounts online and in print of people peeling and crushing the rhizomes, mixing them with water to extract the starch. I've done my best to illustrate the difference between the lateral rhizome and regular rhizome below.

Slotsm

Slotsm is an acronym coined by Sam Thayer referring to a "small lump of tender starchy material" at the base of the plant surrounded by the rhizomes. If you're harvesting a large amount of cattails they can end up being a decent amount of food.

They're edible raw or cooked, but have a tendency to discolor if undercooked, as you can see below. I go over paring the base of the plant and extracting the slotsm in the video.

Do you cook with cattails, have a part you prefer to eat, or have anything else to add? Feel free to leave a comment to share with others.

Becca

I've made a veggie burger--a cattail meatloaf patty--from pollen, egg, a bit of flour, onion, and more. Quite good.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Becca. This is a great idea.

Gilbert

Oops. My mistake too. As in castellano, ancho is wide, angusto is narrow.

Gilbert

OMG! Angustus means wide, augustus means admirable or venerated.

Cat tails are both!

Heather Wood

Brilliant post. Wonderful compilation of the kitchen aspects of the cattail. And the khirret was fascinating to read about, although I'm not sure that I would use my scant stores of pollen to try it. I'm too fond of other uses for pollen.

And thanks for your remarkably good cookbook that has added so much pleasure to my foraging.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Heather

Tammie

Thank you, i have always wanted to learn more about cattails.

I tried one once upon a time. It was delicious. Time to try it again.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Tammie. They’re good, it’s just the sourcing the sourcing that’s tricky.