When I first wrote about my experience detoxifying and eating Amanita, the fly agaric, some eight years ago now, I remember getting plenty of chippy comments from people in the mushroom community portraying me as a reckless, attention-seeking newb, which I expected, and understood. Muscaria is a polarizing mushroom, to say the least.

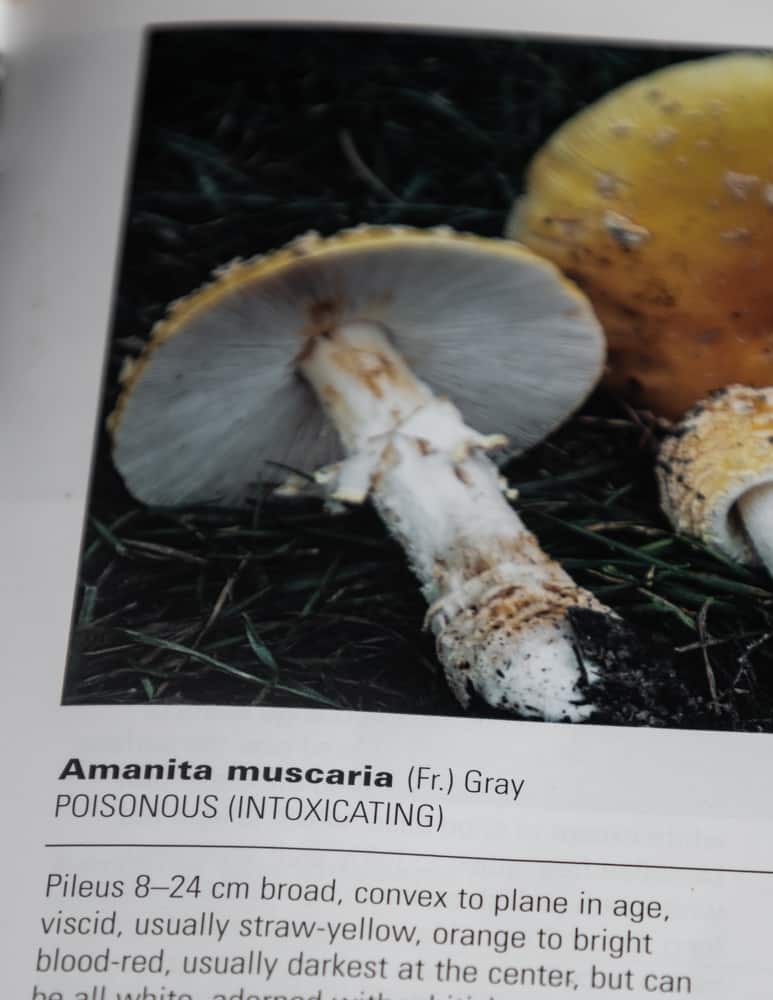

It's widely known that if you eat Amanita muscaria raw, or even cooked from raw, you will get sick.

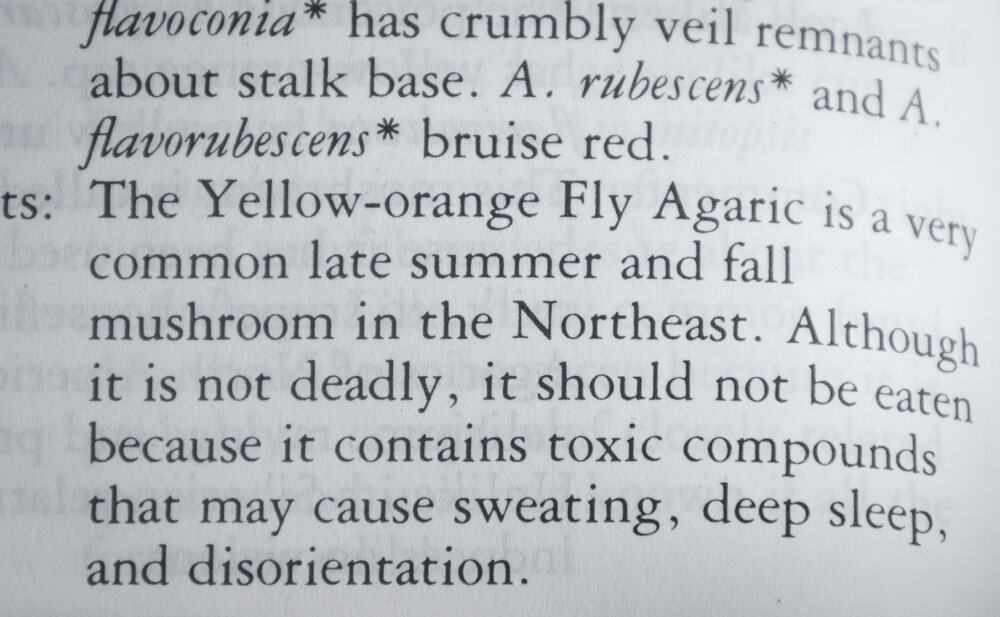

It's also widely known that the mushroom contains "other" compounds, that, when ingested after the right preparations, such as dehydrating, has been used as a narcotic, the sale of which is not at all uncommon under the table at local wicca shops. Personally, I've never consumed it for anything other than culinary purposes.

What isn't widely known, is that muscaria is also a traditional food in the form of fermented pickles in Japan (although it seems to be in a very small, localized region). It's also documented in Russia.

Culinary traditions involving fermentation of wild mushrooms are uncommon, and I know of only one other traditional mushroom fermentation in the salt pickling of milk caps and other mushrooms in Eastern Europe, which it seems, at least to me, is still prepared more or less regularly by their mushroom hunting descendants in the United States, if online mushroom groups are any barometer of use.

Bias in the literature

Every modern field guide I own makes no mention of traditional food practices involving muscaria. I'm not trying to say everyone should eat muscaria, or that it's some huge revelation, but the examples of Western scientific bias ignoring food traditions is nothing new, Scandinavian murklor (Gyromitra) being another good example.

On occasion, I've even seen guides branding the mushroom's image in books with the same dreaded skull and crossbones applied to it's lethal cousins in the Phalloideae, conveying the message that this mushroom is poisonous, and, if you make a false move, potentially deadly.

I knew Amanita muscaria could be rendered edible after boiling, but I had never heard of any specific culinary traditions featuring them until I read a paradigm-shifting experience posted by David Arora on one of the online mushroom groups I'm in. It was a fascinating, exciting read-one of many he's shared online which are not exactly easy to locate.

From an eater's perspective, there's a very big difference in trying to enjoy something that has been "rendered edible", and sampling a culinary tradition documented first hand by a respected mycologist.

Before I forget to mention it, David wrote an academic paper on the subject with a lot of myth-busting, fascinating, and even off-putting tidbits (19th century testing on canines, etc) It's well worth the read, even if you only glance at the abstract.

The entire article can be viewed and downloaded here: A Study of Cultural Bias in Field Guide Determinations of Mushroom Edibility Using the Iconic Amanita Muscaria as an Example. I found it pretty interesting.

In pursuit of pickles, by David Arora

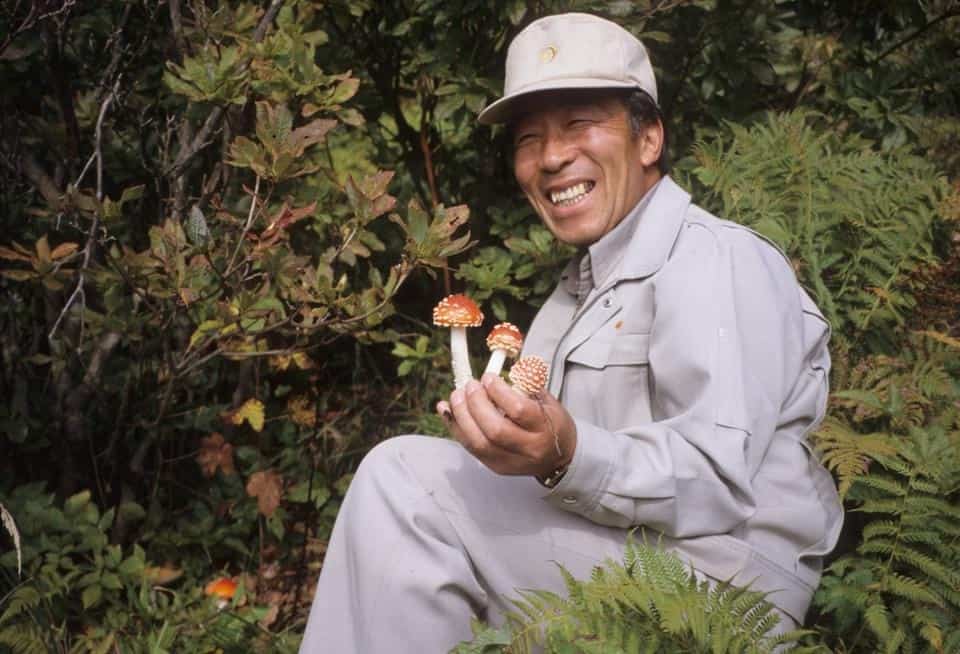

Here's an excerpt from some of David's posts on his travels to the area. "20 years ago I spent almost a month in the town of Ueda, Japan, learning about the localized traditional use of Amanita muscaria as food (mainly pickles), I took many film photos but had no digital camera at that time."

"Last month I decided to return there to see if people were still gathering A. muscaria. and if they were, to digitally document the preparation. I was accompanied on this trip by culinary historian William Rubel, my co-author on a paper on edibility criteria for field guides that used Amanita muscaria as the main example. Also accompanying me were his partner Jane Levy (another culinary historian), and Wendy So (whom some of you know as a fabulous cook with a strong interest in Amanita muscaria as a food). It was my third visit to Japan, William and Jane’s first, and Wendy’s sixth."

"Unfortunately I had lost all contact info for the people I met 20 years ago, so we had to start from scratch with no local contacts at all. I scanned a few photos of people from my previous visit and loaded them into our phones on the off chance that someone we met would recognize one of them. None of us speak Japanese so we relied heavily on Google Translate."

"Old traditions, especially localized ones, are dying out all over the world, and the preparation of Amanita muscaria pickles appears to be no exception. We didn’t see any mushroom gatherers with big sacks of muscaria as I did 20 years ago. In fact, we didn’t see any mushroom gatherers at all, though certainly there are some."

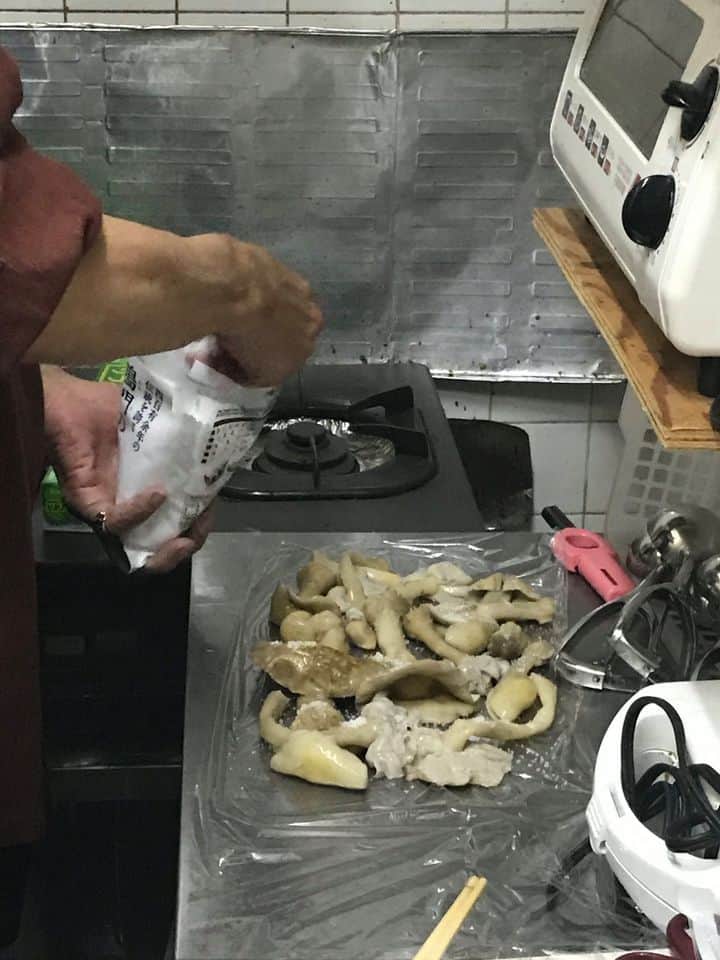

The salt pickling process

"The mushrooms are boiled for 20-30 minutes, then drained and rinsed. Finally they’re packed in 3-5% salt and fermented, for months under refrigeration."

I find it a little depressing to imagine how many interesting food traditions that hold more value than just calories have been slowly extinguished and forgotten. Even if the practice is only in a small area, I see no reason to disregard it as a novelty, or not worth examining, as some people have commented here.

Of course, you know that after reading about something so obscure and fascinatingly funky I had to try fermented muscaria pickles. Well I did, and, they're really not bad, I've actually been (gasp) enjoying them.

All of my instincts made me presume that eating anything boiled within an inch of its life would taste like nothing afterward, but that's not exactly true, and I think muscaria pickles are a pretty cool example.

I've fermented plenty of mushrooms, but isn't something I reach for often. Fermented wild mushrooms can be good, in the right place, but those places are few and far between, as the finished product can be very strong tasting.

And, depending on the particular species, the fermentation process is prone to making many mushrooms mushy, causing them to break down into pulpy, brown slimy goo, which, while not bad if you're making a puree, isn't exactly appetizing either.

Muscaria retains a great texture, and more flavor than you would expect, making this one of the most interesting wild mushroom recipes I've made. I can only presume that other edible amanitas, like velosa and mushrooms from the rubescens group, both of which I've also eaten (the former being excellent, the latter less-so) should produce a similar result.

Cooking, detoxifying, and fermenting

Finding the mushrooms is the difficult part, cooking is relatively easy, and will take about 30-45 minutes for the method I've used here.

You cut the mushrooms into pieces, put them in a pot of water, boil, drain, immerse in salted water, and let sit on the counter like you would sauerkraut in brine. After a while, say 5-10 days, you put them in the fridge, where they'll continue to age more slowly over the months.

In my first batch a few years ago, the first thing I noticed was that, gradually during the aging process, the mushrooms were no longer sitting in clear brine: they were immersed in a beige mushroom liquor.

Like honey mushrooms, they gently thicken the liquid too over time, but it's not mucilaginous like okra, it's more silky and subtle.

My latest batch I'm eating as I write these were just warmed up in a bowl of miso soup, a preparation one of muscaria pickers shared with David Arora. It's excellent, and at least for me, the best part is the texture.

All the amanitas I've eaten have been similar in that the stems are a sort of chewy but tender mushroom bite, that, because of the hole in the middle, always reminds me of calamari. Muscaria is no different.

After fermenting and aging for a while, the mushrooms keep a delicious chew to them, and will sublty pick up aromas you add to the jar, although the basic traditional method seems to be nothing more than salt, boiled mushrooms and water.

Miso soup is the only way I've enjoyed them so far besides of of the jar, and it's been hard to find a better preparation, especially as their "silkyness" dissolves into the broth. Here with homemade miso made from flint corn, a few violet greens, and scallions. Tofu seems hardly necessary but I don't mind it. To make it, just chop the mushrooms into bite-sized pieces and add them to your favorite miso soup.

How much salt?

I use a 3% weight of salt by volume here, so there will be a little less funk to the pickles, and the fermentation will be slower. If you want more tangy lacto-zip I'd use a 3-4% concentration of brine, or even 2% if you want them to sour quick (see my notes below if you're unfamiliar with that).

Many of the common, edible milkcaps will be good like this too, as well as the hot and/or acrid ones, although the latter may need longer aging to soften the flavors.

Safety

It goes without saying that this should only be attempted by people who can confidently and correctly identify Amanita Muscaria, since lethal amanitas grow at the same time of year, often in close proximity.

Please watch my video on detoxification of Amanita muscaria to familiarize yourself with the process beforehand if you would like to try them.

Japanese-Style Muscaria Pickles

Equipment

- Mason jars you can start with a pint size

Ingredients

- 8 oz Amanita Muscaria as fresh as possible

- 13 grams Kosher salt as needed

- Splash of whey or juice from another ferment

- Filtered water

Instructions

Detoxify the mushrooms

- Cut the mushrooms into pieces (see my video for reference) put in a pot of water at a ratio of 6 quarts of water to each 1 lb mushrooms

- Cover the pot and bring the mushrooms to a boil, still with the lid on, then set a timer for 15 minutes.

Salting

- After 15 minutes, remove the mushrooms rinse them vigorously and dry well, then put them in a glass jar or other non-reactive container placed on a scale tared to 0 in grams.

- Add water to cover the mushrooms by ½ inch, weighing the water and mushrooms in grams as you pour it in. Multiply the final grams by .03 or 3%, then add that many grams of salt to the jar. A pint jar is a good place to start, for that, you can use a tablespoon of kosher salt, or roughly 13 grams. Also remember that a pint is one pound, or 448 grams, and 448 x .03 = 13.44 grams of salt. (You can use anywhere from 2-5% salt here for reference).

- Add a dash of sauerkraut juice or fermented brine if you have some to speed up the process.

Fermentation

- Shake the jar, weigh the mushrooms down with a clean stone or clingfilm, screw on the lid, and leave in a dish to catch any liquid at room temperature for 5 days, and up to 10, or until they taste to your liking. The mushrooms should be covered with liquid the entire time.

- After that, refrigerate the mushrooms. The mushrooms will continue to age a bit in the fridge. If you want a stronger flavor, leave them out for another day or two, tasting them regularly.

- They'll last for a long time if always kept completely submerged in liquid, and will continue to develop as they age.

Video

Notes

Fermenting with a vacuum bag

You can also ferment the mushrooms in a vacuum bag after boiling. To do that, dry the mushrooms well. Weigh the mushrooms in grams, multiply the number by .03, or 3%. Add that amount of salt, mix well, and vacuum seal.Nutrition

More

Amanita Muscaria: A Poisonous, Hallucinogenic, Edible Mushroom

Suzanne Myers

Thank you for this recipe, Alan. I have been detoxifying and enjoying Amanita muscaria according to your instructions for 3 seasons, and decided to try this recipe with my current abundance. I’m wondering if you could describe the aroma of your ferment, because I’m slightly worried about mine. It smells like something between Muenster and Limburger cheese. I have tried small bites and, like a stinky cheese, it tastes good and the texture is beautiful….but should it smell like that? I don’t have a lot of fermentation experience.

Alan Bergo

There will be some aroma with ferments. It should be bubbly, with no mold. Refrigerate it to slow the fermentation.

Tomasz

Hello, North American species within A.muscaria group include: A.muscaria var. guessowii, A.muscaria subsp. flavivolvata, A.persicina and A.chrysoblema. The "real" A.muscaria occurs only in Alaska. The ammount of toxic compounds in these varieties may be different than in the Japanese/Eurasian A.muscaria. I think it's worth noting 🙂

Alan Bergo

Thanks Tomasz.

Ryath

Thank you for the post! I'm not leaving a rating because I haven't tried the recipe yet.

I'm putting together a presentation looking at language/culture and mushroom name translations. I am a cook, mycologist, horticulturist and a French/Japanese Californian 🙂

It should come as no surprise to folks that some foods require the right preparation to make them tasty! Cassava, morels (poisonous raw, Monomethylhydrazine), and nettles just to name a few!

I just listened to William Rubel speak about some of his experiences in Japan during the Radical Mycology Convergence in Mulino, OR. Not only has muscaria been honored as food for centuries if not longer, they are now also being remembered and appreciated as medicine (also long history of use for such), but that's tricky (dose, preparation, variability in constituent concentrations) and why so many field guides list this mushroom as poisonous, probably simply for liability issues even if the authors are informed about such nuance. I'll be teaching a course about this if anyone is interested. @funga.dragon on IG

Alan Bergo

Thanks Ryath, fun info there.

Jacqui

so ... I have a jar of these going on my counter. I boiled then for a long time in a lot of water, which I pitched. I rinsed them, weighed them and their necessary water, added the right amount of salt and spooned in a few tablespoons of the brine from a jar of lacto-fermented green tomatos. Not a lot has happened in this jar. No bubbles or any obvious fermentation action.

I made kimchi a few days ago and those jars are burbling up a storm, so I added another spoon or two of the escaped kimchi juice.

I just tried the pickles and they are quite sour despite the lack of obvious fermentation. Good flavour but they are a bit slimy... I suppose that is to be expected.

Alan Bergo

That's interesting. I didn't have any trouble with mine fermenting pretty quick.

Greg Taniguchi

Ok, this article is just too cool. It’s the first article I have seen of yours, but the information to photography is so nicely done.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Greg

Terry Allaway

Alan, Thanks for this article and the references. We are always surrounded by muscaria in the fall, just after the porcini, here on the north coast of California. I had recently heard of locals consuming these after boiling, but like you, assumed anything boiled for awhile was not worth my time. I am already well-practiced at various fermentations, but this wasn't even in Katz (The Art of Fermentation) and it never even occurred to me to give it a try. As the identification chair of our local mushroom club, it will be a delight to try this out and share with the members during our monthly potlucks. I can't wait to open this door for them!

Terry Allaway, Smith River, CA

martin

"Culinary traditions involving fermentation of wild mushrooms are extremely rare" Really? I have lots of Polish cookbooks alone that have tons of recipes for fermenting mushrooms, wild and otherwise. And that's not accounting for all the Russian, Estonian, Latvian and other cultures that I know for sure have traditions in this manner. My father was from Gdańsk and was an avid mushroom hunter. I can't recall a time in Northern Minnesota when he returned from a hunt with a basket of mushrooms that didn't involve pickling many of them (especially Suillus Boletes/Slippery Jacks).

Alan Bergo

Martin, it's relatively well-known that salt-pickling is common in Eastern European mycophagist traditions, but, outside of that, in comparison with other traditions around the world, it is absolutely not common, which would explain why it is not outlined in any book on fungal cookery that I have read or owned, ever, including those specifically covering the cultures you're referencing. Just because you know the practice well, doesn't mean that it's common around the world.

Martin

Hmmm. I know this will sound snarky (and my intent is to be more humorous but such are the limitations of typing things out), but if you haven't encountered this type of preparation in Polish cookbooks that you've owned or read, then you aren't reading the right ones. I can open any of the ones I have and easily find a lactose ferment for mushrooms. The most prominently known preparation would be sauerkraut with wild mushrooms. I have many, many, many Polish cookbooks and they all contain instructions for that. I also have many simpler recipes in the same books for mostly Chanterelles or the aforementioned Boletes that require nothing but salt, the mushrooms and weights. However, I wholeheartedly agree with your closing statement that these types of ferments are not common throughout the world, but I am encountering them being done nowadays more and more by people from other cultures. Your Muscaria preparation sounds wonderful, by the way! I have eaten them before by doing the multiple boiling method and have enjoyed the results, but I never thought about taking it any farther.

Alan Bergo

Martin, I'd love some book recommendations if you them, none of mine mention them.

Martin

If you can, I would start with a copy of Juliusszowa Albinowska’s 1916 cookbook “Grzyby w Gospodarstwie Domowem i Handlu” (Mushrooms in the Household and Trade). It was originally published in 1916 and has had a few editions printed in English, though they are hard to come by. Her recipe for lacto fermented mushrooms is as follows: “Freshly picked mushrooms should be rubbed with a napkin, one by one, so that no sand, soil or needles are left behind. Throw away the stems. Put the caps in clay pots and sprinkle with fine, sifted salt. Then, weigh them down with a disc and a stone and put them in a dry place. If they don’t release enough liquid, pour 1-2 glasses of boiled water over them. Serve seasoned with vinegar, oil, onion and black pepper.” Albinowska’s technique is exactly how I was taught to ferment boletes. An easier to find book might be “Polish Cookbook” by Sofia Czerny. This one should be very easy to find, I often see copies of it on Etsy and it is readily available in English. Czerny’s recipe is fascinating as she calls for other herbs and spices to be added to the salt, which results in a wonderful fermentation, in my opinion.

Tomasz

I live in Poland and I can confirm, that salt pickling is not very popular nowadays, but it used to be rather common in the past. It is still practiced in the eastern parts of Poland, or by Ukrainian immigrants, but the practice is more common in Ukraine and Russia. The most commonly pickled species are various spicy milk caps (L.piperatus, L.torminosus, L.vellereus etc.).

Alex Bilodeau

Interesting story as always! Do you think Amanita jacksonii would be good too? Thanks.

Alan Bergo

Absolutely I do, and I'm jealous that you have them near you. Someday I'll get to taste one.

Lissa Streeter

Yay ! Always Tops Forager Chef ! I see a lot of these here in our Paris.area. actually it’s a really common one. But have never done the research to think I was knowledgeable enough to eat/cook/serve/survive. Heard Russians boil these and eat them too but had never followed up on the specifics like you do so carefully here !

So impressed with the quality of your posting and work. Thanks for sharing it with a wider world 🙂

Lissa Streeter, Paris

Debbie Viess

Hi Alan. I wouldn't exactly call muscaria pickles a "traditional" Japanese dish, considering that only the tiny Sanada Town in Nagano Province ever did this, and only a small fraction of the citizens of that town ate muscaria pickles! The reason that restricted tradition is dying out is because youth doesn't want to go through all of that bother; most consider muscaria to be a seriously toxic species, feared even by those that do eat it! Making these pickles took WEEKS, not days. All of this was discussed in Phipp's Master's thesis: Phipps, Alan. 2000. Japanese Use of Beni-Tengu-Dake (Amanita muscaria) and the Efficacy of Traditional Detoxification Methods. Master’s Thesis, Biology Department, Florida International University. Here's a pull-quote from my article on eating muscaria: "Further Reflections on Amanita Muscaria as an Edible Species:"

"The process of making them [muscaria pickles] is extremely involved (Phipps, 2000, p. 62). There are four steps to pickling muscaria, as relayed to Phipps by Sanada Town muscaria pickle devotees: boiling for ten minutes, or five minutes three times, washing, salting and soaking. Mushrooms are often initially boiled until all color is removed; the water is always tossed. After boiling, the mushrooms are rinsed under running water for 1-3 minutes. Mushrooms are then packed in salt and compressed, and left for at least one month. Prior to consumption, pickles were soaked for several hours or overnight to remove the salt (and any remaining traces of the toxins). These muscaria pickles were then used as culinary accents, not meals. They were and still are eaten for special occasions only, or served to special guests (Phipps. 2000, p. 37)."

Pretty much any edible mushroom will make a fabulous pickle, Why start with a toxic species?

Alan Bergo

Debbie, thanks for sharing some direct references. David's enthusiasm was contagious and, believe it or not, these are quite good. While you can make pickles out of plenty of mushrooms, as I note, lacto-pickles will vary in quality greatly from species to species and those that hold texture are worth noting. Fermented Shiitake turn to mush, as do golden chants. The fact that these hold their texture after fermentation is a nice quality, and is part of the reason I mention other, non-toxic amanitas in this post, since people familiar with them could potentially use alternate species like blushers or velosa to get a similar effect. The process described in Phipps will work too, but includes some arbitrary instructions not necessary for the purposes of precise fermentation that can alter the desired end result. My method here is precise and easy to follow, with no estimation or vague instructions like handfuls of salt often found in older recipes that obscure the process for those interested in it.

Like it or not, it's a tradition, and the size of the place where food traditions come from doesn't have any weight on their value to me. If, as your reference states, they're reserved for special guests and special occasions, I'd assume they're probably not as dreadful as you're implying.

Sam Schaperow

My thoughts are blushers are also toxic, but because they're more easily rendered edible, it makes the process a bit easier if you have lots of blushers. But, it is easier to find masses of fly agaric than blushers, at least for me. Also, a comment on your main article is that white blushers taste different than regular blushers that I found in the Northeast, so I would not personally want to consider both in the same taste category. Regular blushers can have a delicate white fish like flavor, but I have found the white plushies to be as Bland as their color relative to regular blushers. Lastly, this fermentation recipe does look intriguing. I hope people will try it and we can see their comments.

Alan Bergo

Thanks Sam. Yes, I've only eaten 1 blusher, and I know there are better ones out there. I'd definitely eat more of them, especially the chunky ones I see people picking and posting from Europe.

Dayana

Excellent, I have Muscaria everywhere right now. Very interesting, thanks for the history!

Mush

Love the history. Do you eat abortive entoloma? How do you

Prepare? Text says eat with caution!

Thanks

Alan Bergo

Yep, just ate a bunch yesterday. These are a safe edible. What guide are you using? If possible I'd love a picture of the warning text, I haven't seen that before. Honey mushrooms that grow near them you definitely need to cook thoroughly.

Michael Neely

Very cool, thanks for the article! I’ve done something similar with Lactarius rufus for years; brine fermenting them after two changes of boiling water to get rid of the hot peppery nature when they are raw. Definitely going to give this a try with A. muscaria!

Alan Bergo

Thanks Michael, I've really been enjoying them. They keep more flavor than you'd expect.